For more than a decade, Abu Sajad's small convenience store was a fixture in Doura, an industrial neighborhood in south Baghdad. Customers came for friendly service and the ease of buying rice, tea or cigarettes a few blocks from home. Abu Sajad, a 44-year-old with salt-and-pepper hair, would even let regulars--Sunnis, Shiites or Christians--run up a tab. But not long ago, Abu Sajad was found in a pool of his own blood. Sunni insurgents had shot him 11 times with an AK-47. Shortly afterward, his widow and four children left for Karbala, a Shiite town in the south. His brother, Abu Naseer, decided to move to Al Kurayat, a predominantly Shiite neighborhood in eastern Baghdad. The Doura shop was closed, another debris-strewn relic of an Iraq that may no longer exist. "I have no reason or explanation why he was killed except that he was Shiite," says his brother.

Across the country many Iraqis have begun to fear the worst: that their society is breaking apart from within. "The vast majority of the population is resisting calls to take up arms against other ethnic and religious groups," said a senior Bush administration official whose portfolio includes Iraq but who is not authorized to speak on the record. Yet he also said there "is a settling of accounts and a splitting apart of communities that [once] did business together." Sunni insurgents, trying to prevent political dominance by the Shiite majority, are killing them in great numbers. Shiite militia and death squads are resisting. Now many ordinary citizens who are caught in the middle aren't waiting to become victims. They're moving to safer areas, creating trickles of internal refugees. "There is an undeclared civil war," Hussein Ali Kamal, head of intelligence at the Ministry of Interior, told NEWSWEEK.

The outcome of these conflicts--and Iraq's future as a unified state--may well be riding on a critical nationwide vote planned for next week. Iraqis will decide, in a U.S.-orchestrated referendum on Oct. 15, whether to accept a permanent constitution drafted by the transitional National Assembly. Yet many worry that even if the constitution passes as Washington hopes, it will only worsen the disintegration underway. Key provisions allow for separate regions to control water and new oil wells, dictate tax policy and oversee "internal security forces"--to become autonomous, in effect. A confidential United Nations report, dated Sept. 15 and obtained by NEWSWEEK, cautions that the new constitution is a "model for the territorial division of the State." And in congressional testimony last week, Gen. George Casey, commander of Coalition forces in Iraq, said the U.S. occupation may have to continue longer because the draft constitution "didn't come out as the national compact that we thought it was going to be."

Others say Iraq can exist, even thrive, under such a loose federalist system. What is not in dispute is that at the most basic level--of neighborhoods and communities--the tissue of Iraqi society is already rupturing. It's not just Shia who are displacing themselves to be among their own kind, though they are the main victims of the Sunni-led insurgents. Many Sunnis, terrified of death squads and Shia-dominated police who look the other way, are fleeing Shia areas even if they don't support the insurgency. Dozens of Sunni families left Basra in the past year, fearing attacks from Shiite militias that dominate that southern city. "For a Sunni family like mine that was swimming in a lagoon of Shiites, it was almost impossible to continue living in Basra," said one refugee, Abu Mishal. Mahmoud Othman, a Kurdish member of the National Assembly, concurs: "We never had this even under Saddam... This is very dangerous."

For many Iraqis, the only sense of security they can find after two and a half years of chaos is in the bosom of their sect or tribe. One central government after another in Baghdad has failed to establish order. After two years of training, the new Iraqi Army has but one fully independent battalion--about 500 men--centcom Commander Gen. John Abizaid told Congress last week. So, not surprisingly, militias and warlords have begun to take over and tend to their own.

All this is the opposite of what was envisioned a year or so ago. As part of the hopeful U.S. vision imposed by then U.S. viceroy L. Paul Bremer, 10 militias nationwide were to have been folded into the new Iraqi military and police. "This decision was never activated," says Ammar al-Mayiahi, Basra chief for the Badr Brigades, the militia of the Iranian-linked SCIRI party. "And Badr is still in control." In fact, several big militias are now operating across the southern Shiite provinces, often warring with one another for political and administrative advantage. All Iraqi Arabs, whether Sunni or Shia, are reluctant to travel to the Kurdish north. The Kurdish peshmerga are by far the biggest native force in the country, some 75,000 strong. They do not fly the Iraqi flag or wear Iraqi Army uniforms. "The most dangerous scenario is that the regions form their own internal-security services and they start operating with the sanction of local authorities," says a Western official in Baghdad who was forbidden by his superiors from speaking on the record. "Then the country could break up."

Yet many local authorities are already deferring to the militias. In Sholeh, a predominantly Shiite neighborhood in western Baghdad, fighters working for the Mahdi Army of radical Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr recently allowed a NEWSWEEK photographer to accompany them. The commander, Abu Razaq, who had a black scarf wrapped around his head and an AK-47 slung low on his right hip, said he gets no trouble from the Americans or Iraqi police. "We coordinate very well with the police," he said. Why are the police so compliant? "They are too scared to arrest the terrorists when they have a target. So they coordinate with us and we go inside and storm the houses."

It isn't clear whether this reversion to ethnic roots will lead to national disintegration. Iraqis have had a relatively brief experience of nationhood--about 80 years. Most of that has been unpleasant: 12 years of British colonial rule, an interlude of monarchy and then various strongmen and the brutal three-decade nightmare of Saddam's Baath Party. What is happening now, catalyzed by the killing and lack of security, is in part a return to the natural decentralization that once dominated Mesopotamia, as it was called. Iraqi Vice President Adel Abdel Mehdi, seeking to put the best face on things, told NEWSWEEK that the constitutional process will bring Iraq back to a more halcyon era when it was a loose system of communities centered around the three biggest cities, Basra, Baghdad and Mosul. "The decentralized system worked here for thousands of years," he says. Under the new constitution, Mehdi adds, Iraq "could be like the Arab Emirates--each state would have its own investment policy, its own costs, a combination of different models."

Even so, U.S. officials were stunned in August when Iraq's most powerful Shiite politician, Abdul Aziz al-Hakim, demanded the same rights given to the Kurds and sought to create a Shia superregion in the south. Such a region could become a powerful new ally and satellite for Iran And in the worst case, the new Iraqi Army the United States is training--which is mainly Shia--could become the core of a Shiite army. U.S. officials believe that Iranian intelligence agents have infiltrated the most senior levels of the Iraqi government.

Against Shiite power, many Sunnis believe that the only leverage they have left is the insurgency. As a result, some U.S. officials worry that Sunni support of the insurgents will continue no matter what. If the constitution does pass, the Sunnis could feel even more disenfranchised. If, on the other hand, the draft is rejected by a two-thirds majority in three regions--the threshold for defeat under the law--the insurgents may declare success.

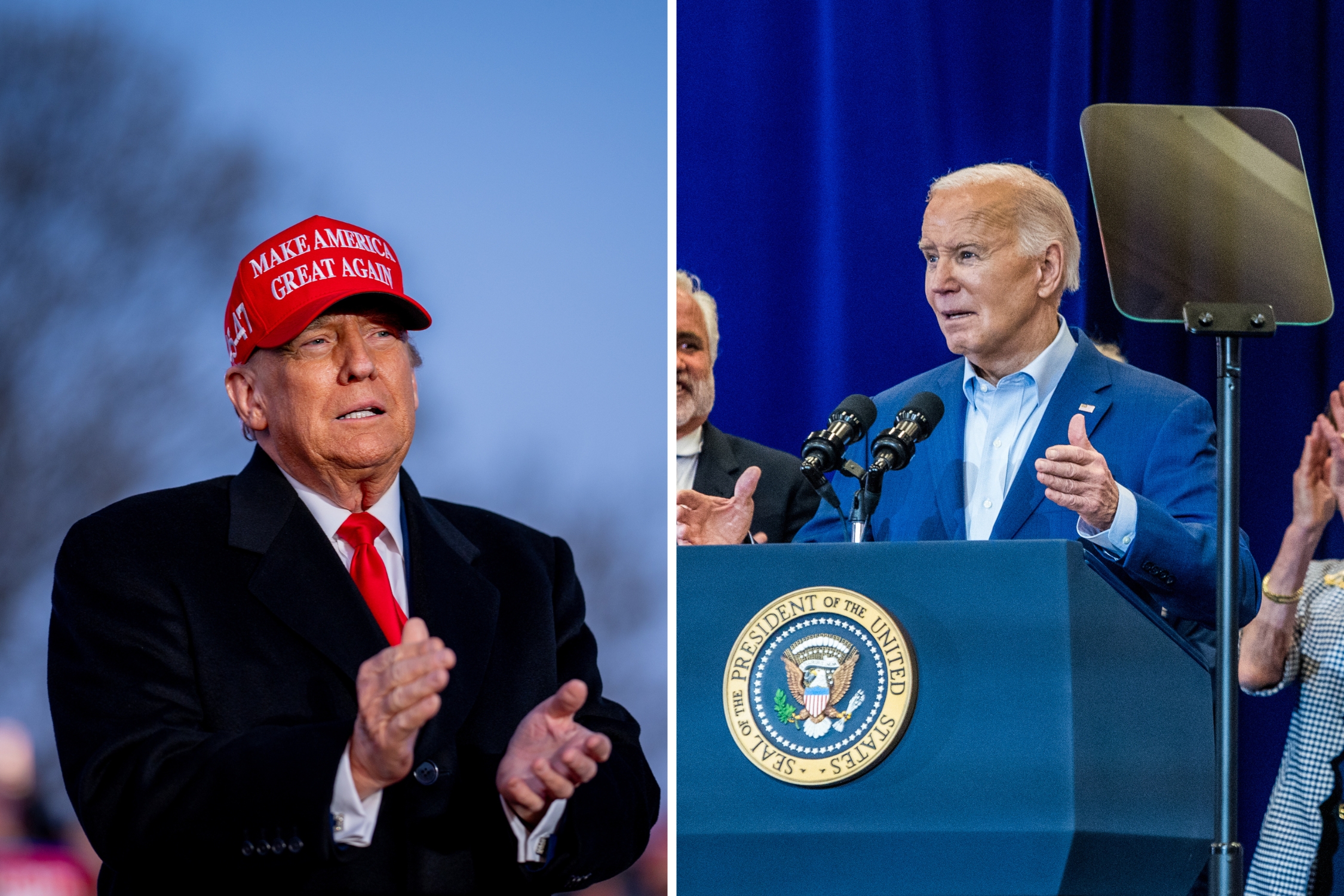

The administration clearly is concerned. Gen. Peter Pace, the new Joint Chiefs chairman, gave a notably bleak Iraq briefing recently to the White House, breaking with his relentlessly optimistic predecessor, Gen. Richard Myers. Top military and civilian officials are particularly focused on dwindling domestic support for the Iraq occupation. This week, President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney begin a new speaking tour to shore up that support. But even if America does "stay the course," to use the president's favorite phrase, many wonder whether the country he liberated will still be there at the finish line.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.