Updated |

On a cold afternoon in February, several former American officials hurried to the Hilton hotel in Berlin, a city long known for its Cold War spies and intrigue. They had traveled there for a private meeting with senior representatives from North Korea, the most reclusive government in the world. Over the next two days, the Americans gathered in one of the hotel's modern conference rooms and listened to a surprising new proposal. Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un, the North Koreans said, wanted to resume negotiations in hopes of ending decades of hostility between the two countries.

The timing was significant. A month earlier, the U.S. had agreed to talks to formally end the Korean War, but that effort collapsed when Washington demanded the North's nuclear weapons program be part of the discussions. A few days later, the Hermit Kingdom, officially known as the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), set off what it claimed was a hydrogen bomb at an underground site in the country's rugged northeastern mountains. That nuclear test, the country's fourth, left U.S. officials scrambling for new ways to deal with the threat from one of the world's last communist regimes.

After the Berlin meeting, the former U.S. officials promptly returned to Washington to report to the White House. Sitting at a conference table in the Situation Room, they told the president's top national security advisers that Pyongyang was prepared to stop testing nuclear weapons for a year. In exchange, the U.S. and South Korea would have to suspend their annual joint military exercises that the DPRK found provocative.

The offer was similar to one North Korea had made a year earlier, and the White House had rejected, largely out of anger over Pyongyang's alleged hacking of Sony Pictures. This time, however, North Korea wanted to talk about officially ending the Korean War (it technically stopped with an armistice in 1953). And Kim was now willing to wrap the nuclear issue into the discussions. The president's advisers listened closely without comment.

Ending the Korean War has long been a priority for North Korea's young dictator. Analysts say he regards it as a way to remove the threat of tens of thousands of U.S. forces based in Japan and South Korea. His nuclear arsenal, experts believe, is both his leverage and his deterrent against an American-led attack. "The H-bomb test was a self-defense measure to protect the sovereignty of the nation from the nuclear threats and blackmail of the hostile forces that are growing daily," Pyongyang's official Korean Central News Agency announced in January. The news agency went on to say that North Korea would abandon its nuclear program only if "the U.S. rolls back its outrageous hostile policy toward the DPRK and the forces of imperialist aggression stop infringing upon our sovereignty."

Once you cut through the old-style communist rhetoric, some analysts say the Obama administration missed an important signal there: Kim may be ready to cut a deal with the U.S.

The White House declined to comment on the new North Korean proposal, which has never been made public before now. But a growing number of analysts and former officials say the Obama's administration's North Korea policy could prove to be a dangerous failure, largely due to misinformed assumptions about Pyongyang's fragility, China's outsized political and economic influence with the North and a perception of Kim as little more than a cartoon villain. They're urging the administration to accept North Korea's latest offer and restart negotiations. At the very least, they say, Pyongyang's proposal could slow the country's nuclear program and begin talks to defuse more than 60 years of tension on the Korean Peninsula. At best, it could produce another legacy agreement like the one President Barack Obama reached with Iran and his diplomatic openings to Cuba and Myanmar.

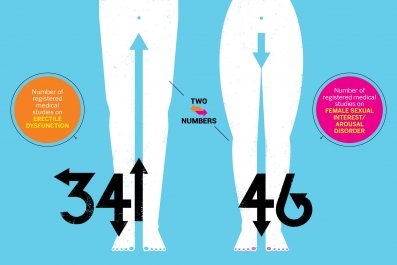

But if the White House sticks to its current policy, critics warn the DPRK could have as many as 100 bombs by the end of this decade. As James Church, the nom de plume of a former CIA operative and expert on North Korea, puts it: "Every time they test, they learn so much more."

'Watch Your Toes'

By the time Obama took office in 2009, the North Koreans had already conducted their first nuclear test, and two nuclear agreements had already collapsed amid mutual accusations of cheating. But Obama quickly reached out to North Korea in hopes of resuming talks. Pyongyang's response: a second nuclear test.

Obama then adopted a hard-line approach that essentially echoes the stringent policies of President George W. Bush. Obama refused to engage in direct talks with Pyongyang until the regime first demonstrated it was willing to give up its nukes. In the meantime, the U.S. tightened sanctions against North Korea, believing the poor, isolated country would eventually collapse or agree to denuclearize.

Two years later, famine forced Pyongyang back to the negotiating table. In early 2012, Obama and Kim reached an agreement that required the North to freeze its nuclear and ballistic missile programs in return for 240,000 tons of U.S. food aid. But soon afterward, that deal fell apart when Pyongyang fired a missile to launch a satellite. In 2013, North Korea conducted its third nuclear test.

In 2015, after the U.S. and Iran agreed to a historic nuclear agreement, Obama appeared to soften his approach to Pyongyang in hopes of making a similar deal. He dropped his condition that North Korea curtail its nuclear program before direct talks about its nukes could commence. But Pyongyang wanted to talk only about officially ending the Korean War, and that effort dissolved. After the North's fourth nuclear test in January, the U.S. and the United Nations Security Council imposed new penalties on Pyongyang.

Over the past seven years, none of Obama's diplomatic efforts have changed defense cooperation between the U.S. and its ally South Korea. The two countries have continued conducting their annual joint military exercises, which Seoul described this year as a practice run to "decapitate" Pyongyang. This year's maneuvers were also the largest ever, involving 300,000 South Korean troops and 17,000 from the U.S. During the exercises, the American military test-fired two nuclear-capable intercontinental ballistic missiles—a not-so-subtle reminder of its first-strike nuclear capability. "The message to North Korea has to be, 'So, you think you have nuclear weapons? Well, we have a way of dealing with that, and it's called preemption. So watch your toes,'" says William Brown, a former CIA analyst.

Despite the recent muscle flexing, when asked to state current U.S. policy toward Pyongyang, a senior administration official indicated the White House is still prepared to begin a dialogue with North Korea before it demonstrates it's ready to give up its nuclear weapons.

Combined with North Korea's offer in Berlin, Church and other experts believe Obama's softer position on negotiations could mean renewed talks. But Church suspects any such move could occur only after the latest U.S. and U.N. sanctions have had enough time to hurt the Kim regime. "We have to prove how tough were are," he says.

Pyongyang Was Right

If some new diplomatic initiative is brewing, Church and other experienced Asia hands stress the White House will need to show a much better understanding of North Korea. That's no easy task when dealing with one of the world's most impenetrable countries. "It's a consequence of the mythology that has built up around [North Korea]," says Church. "It's so easy to accept the conventional wisdom: They're duplicitous; you can't deal with them; they cheat on every agreement they make; Kim is crazy." All these claims, he says, are incorrect.

Few would challenge Kim's reputation for brutality. After succeeding his father in 2011, Kim Jong Il, the freshly minted dictator, then just 28, ruthlessly purged suspected opponents, executing his uncle and former mentor, Jang Sung Taek, plus all of Jang's relatives. Human rights abuses under Kim's rule have prompted a United Nations commission to demand his investigation for crimes against humanity. "So he's cruel," Church shrugs. "Show me a dictator that isn't."

Church isn't the only one who thinks the U.S. needs to re-assess its views of the eccentric North Korean leader. Despite his strange haircut and over-the-top rhetoric, "Kim's not crazy," says Joel Wit, a former State Department Korea analyst. His threats to vaporize New York and Seoul are disturbing, Wit notes, but he calls them a "predictable response" to his—and his predecessors'—fears of being toppled.

Other analysts dismiss the conclusion that North Korea is staggering toward collapse, as Obama has suggested. While famine reportedly killed thousands in 2011 and life in the North Korean countryside remains grim, Kim has stabilized the economy, and for now, the nation is self-sufficient in food, says Brown, the CIA analyst. Meanwhile, visitors to Pyongyang describe a fledgling nightlife, with a growing number of restaurants, bars and karaoke rooms. Private taxis cruise the streets, demanding payment in dollars, and millions of North Koreans now own cell phones. These, Brown says, are signs of North Korea's growing middle class, who have prospered under Kim's limited free market reforms.

North Korea is somewhat isolated, but Brown says Kim has diversified the country's trading partners to include not only neighboring China, but also countries in Africa, Asia and Europe. Increasingly, he adds, people from these countries visit Pyongyang, and North Koreans are traveling to study and work. "A lot is going on," Brown says.

Former officials also say that Kim isn't the only one who cheats on accords. Wit notes that a 2005 nuclear agreement collapsed because Bush slapped the North with new economic sanctions "before the ink was dry." Likewise, Obama's short-lived 2012 agreement restricting nuclear and missile tests fell apart when North Korea insisted the long-range missiles for satellite launches were exempt. And Wit, the former State Department official, says Pyongyang was right. "North Korea," he says, "never agreed not to conduct the space launch tests."

Another major misconception is the administration's conviction that China will use its clout to make North Korea give up its nuclear arsenal. China opposes the DPRK's nukes and supports the latest round of U.N. sanctions, but Beijing shielded its fuel shipments to North Korea and Pyongyang's coal and iron exports from the resolution. The reason: China views North Korea as a buffer against democratic South Korea, which hosts 29,000 American troops. Beijing worries that stronger sanctions would destabilize Kim's regime, send millions of North Korean refugees streaming into China, and perhaps even bring U.S. and South Korean soldiers right up to its border.

"For China, the sanctions are meant to get the North Koreans back to the negotiating table," says James Person, a Korea expert and historian at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. "The last thing China wants is for the North Korean state to collapse."

'The Noose Is Tightening'

Some analysts, including many former administration officials, still believe China remains the key to getting North Korea to give up its nukes, even if takes considerably more time. So far, Chinese authorities have stopped several banks near the DPRK border from handling any more transactions with Pyongyang, according to China's state-controlled media. The reports say Beijing has also inspected the cargoes of ships passing through its territory to and from North Korea.

Over time, as the Chinese increasingly apply tougher sanctions, "the North Koreans are going to have fewer and fewer options," says Michael Fuchs, until recently the administration's deputy assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs. "The noose is tightening."

David Straub, former director of the State Department's Korea desk, agrees. "We've really reached the point of no return," he says. "Either our gradually ratcheted-up pressures will eventually persuade the North Korean leaders that this is not working the way they had expected, or the tensions will become so great in North Korea that there will be some change within the regime itself."

Skeptics maintain that peace talks with Pyongyang are the only way to resolve the nuclear issue. But it won't be easy. Any comprehensive peace negotiations with the DPRK would make the talks that produced the Iran deal look simple. For starters, the two sides remain far apart on the nuclear issue, with North Korea now demanding recognition as a nuclear power and the United States still insisting on denuclearization. Any negotiations would obviously have to take into account the security concerns of South Korea and Japan, both of which have defense treaties with the U.S. The White House announced Obama will discuss the North Korean nuclear threat with South Korean President Park Geun-hye and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe during the two-day nuclear security summit that began Thursday in Washington. Obama will meet separately with Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle to any peace talks: U.S. insistence on human rights reforms. Experts say Kim almost certainly would resist, declaring the issue an internal matter. That would require the administration to calculate how important North Korea negotiations are compared with other issues Obama wants to deal with in his remaining nine months in office. Human rights advocates would slam any talks that sidestep the issue.

Experts also caution that a deal could take years, which would hand responsibility for their final accord to Obama's successor. In the meantime, U.S. negotiators could expect plenty of misunderstandings, tantrums and setbacks. And of course there would be no guarantee that even the savviest diplomats could convince North Korea to cash in its nuclear insurance policy.

But as Kim's latest bomb test demonstrates, the alternative to diplomacy will be a regime with no incentive to halt its nuclear buildup. There's also a danger that North Korea would sell its nuclear technology to terrorists and other outlaw regimes. In 2007, for instance, Israeli warplanes destroyed a nuclear reactor in eastern Syria that had been built with help from the North Koreans. At a time when Obama is stressing the importance of nuclear security, the latest overtures from the DPRK may offer the last best opportunity to achieve peace, or at least greater stability, on the hair-trigger Korean Peninsula. As Wit puts it: "The administration has nine months left."

This story has been updated to include mention of U.S. President Barack Obama's meetings with South Korean President Park Geun-hye and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on Thursday, as well as a a separate meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping.