Update | North Korea claimed to have tested a hydrogen bomb on September 3, its sixth nuclear test and approximately six times as strong as its test in September 2016, according to the South Korea's meteorological administration.

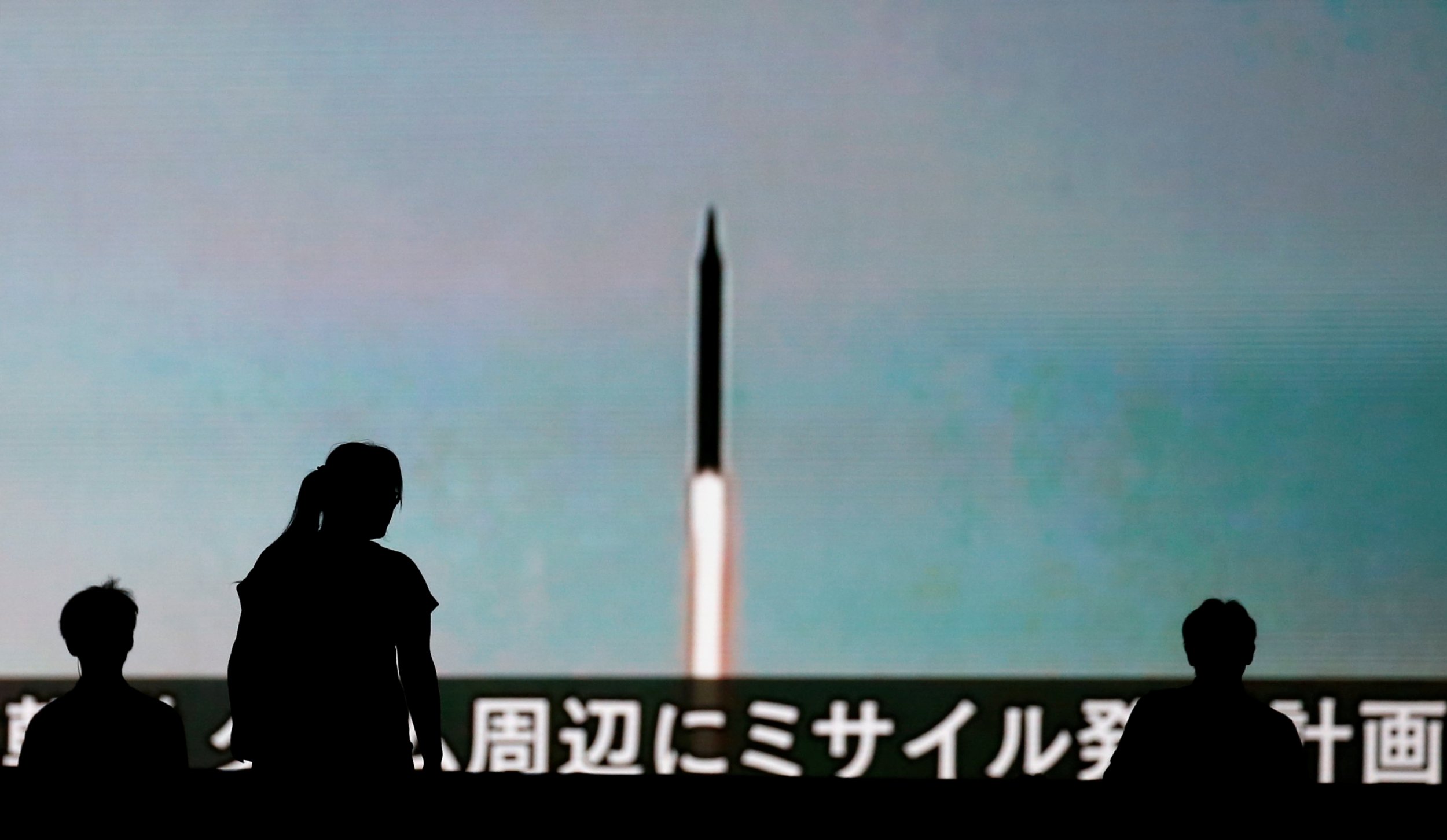

This followed weeks of rising tensions and a war of words between U.S. President Donald Trump and the pariah state about nuclear capability. The spark for the (so-far) verbal fire was Pyongyang's fresh claim in early August that it is able to hit the U.S. Pacific island of Guam with a nuclear strike. North Korea aspires to have the entire U.S. mainland within striking range. Here is what we knew about the bite of the North's nuclear bark prior to the latest test.

How Powerful Is a North Korean Warhead?

Tests involving nuclear explosions show progress regarding the power of the blast North Korea can cause. A 2006 explosion detonated a plutonium-fueled atomic bomb with a yield equivalent to 2 kilotons of TNT, data from D.C.-based think tank the Nuclear Threat Initiative shows. The bomb dropped on Hiroshima by the U.S. military in 1945 had an estimated yield of about 16 kilotons. North Korea's latest tests have since surpassed that figure more than twofold.

Read More: Putin is urging North Korea against using force before meeting China's Xi Jinping

In 2009, a test increased this power four times from the 2006 blast to 8 kilotons; several tests later, a September 2016 blast yielded 35 kilotons. The ability to deliver this blast to the U.S. is the challenge North Korea faces now.

Tests of their missiles' range have shown a considerable increase of capabilities, stretching now to potentially 10,400 kilometers (6,500 miles). These test launches have not been carried out with a nuclear warhead, and the calculations of putting the two together is what keeps North Korea from boasting the ability to fire a warhead at massive distances. Targeting the U.S. mainland requires precisely this sort of capability.

The Warhead Takes Flight

Warhead miniaturization is a crucial step in turning a potential nuclear bomb into a nuclear missile. The process of miniaturization consists of finding the most compact design to mount the physics package—the nuclear payload of a missile—on the ICBM without disruting the missile's flight. The way North Korea is likely pursuing this is by using the common so-called "implosion design," in which the nuclear fissile material is exploded by a chamber of conventional explosives, Matthew Kroenig, nonproliferation expert at the Atlantic Council, says.

"You have your fissile material—plutonium is preferred—in a loosely packed sphere, and you surround it with conventional explosives. You need them to detonate at the same time; otherwise the plutonium blows out the other end."

If the detonations are not simultaneous, the best-case scenario is the triggering of a chain reaction that mostly wastes the fissile material. The worst-case scenario is that it does not cause a nuclear chain reaction at all.

This is the design North Korea is probably already using, says Tom Plant, director of the proliferation and nuclear policy program at London's Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). "Having an implosion design that does it on the ground is quite different than having one that does it in the air, but again, this is not something North Korea is incapable of addressing."

The Warhead Must Survive Space and Re-entry

Despite a report on August 8 by the The Washington Post that "North Korea has successfully produced a miniaturized nuclear warhead that can fit inside its missiles," whether the warhead can survive the ICBM flight is another matter. The distinction can be crucial, Plant says.

"In relation to that particular U.S. intelligence assessment, the language is always worth paying very close attention to. The assessment states that North Korea has produced nuclear weapons for ballistic missile delivery, to include delivery by ICBM," he says. "That's subtly different from saying that those weapons fit in a survivable re-entry vehicle.

"In casual conversation, it may be natural to make the inference between the two," he continues. "In an intelligence assessment, it needs to be absolutely explicit."

Related: Russia's Defenses Are on High Alert Near North Korea, Senator Says

Put simply, the warheads may be designed with the intention of taking off inside an ICBM. The full journey of such a missile would traverse extreme cold and scalding heat upon re-entering the Earth's atmosphere; that is the biggest test for the segment of the missile to ensure the full nuclear punch is delivered on target. If the re-entry vehicle fails to deliver the fissile material through the atmosphere, the strike is a botch.

Beyond the fissile material, the re-entry vehicle would likely have additional engineering features such as heat shields, an ablative shield, potentially the fusing system, Plant says. All must be accounted for in the weight equation.

Would a Bigger Rocket Help?

Currently, North Korea's prospective intercontinental harbinger of nuclear doom is the Hwasong-14 missile. Video from Japanese public broadcaster NHK last month shows it disintegrating as it re-enters the atmosphere.

That could be a show of the re-entry vehicle's problems, says Karl Dewey, CBRN analyst at Jane's by IHS Markit, or the result of a lopsided trajectory during the launch. Other problems may have caused missile ignition, such as a deliberate self-destruction to prevent foreign salvage.

If the Hwasong-14 is flawed, North Korea could theoretically opt to make a bigger missile capable of carrying more cargo. "Easier said than done, however, especially when one considers operational requirements such as deployability," Dewey says. "For example, the Unha/Taepodong is often considered to be for weapons, but the considerable preparation time makes this unlikely."

The missile in question, reported as a possible ICBM during its faltering maiden launches in 2006, has proven physically unsuitable for the job. North Korea expert John Schilling at the University of South Carolina concluded in 2015 that it is "too large and cumbersome" for warhead delivery. The Hwasong-14 remains Pyongyang's main option at present.

Would Russia and China Step In?

Any foreign help could speed up North Korea's ICBM nuclear program. In the past, the Soviet Union and China aided Pyongyang's nuclear energy and missile programs. Moscow assisted North Korea from the late 1950s to the 1980s, helping build a nuclear research reactor and design missiles, and providing light-water reactors and some nuclear fuel. China joined forces with North Korea in developing and producing ballistic missiles in the 1970s. Pakistan also has been crucial to North Korea's nuclear program, sharing its expertise in the use of gas centrifuges to produce weapons-grade uranium.

During the Cold War, however, Moscow and Beijing remained wary of sharing militarized nuclear technology with Pyongyang. Both are currently committed to nonproliferation.

"China and Russia have a strong interest in nonproliferation," Plant says. "I can see a ballistic missile connection from North Korea to Iran, more so than the other way around."

Even that sort of partnership is unsubstantiated in evidence, Plant notes, as the uranium enrichment technology both countries use is different. "What I would be worried about is North Korea acting more as a supplier than a recipient," he says, recalling suspicions 10 years ago that Pyongyang was cooperating with the regime in Syria.

In 2007, Israeli air force jets bombed what analysts believe was a Syrian nuclear reactor in the making, modeled on North Korean designs.

This article was updated to include early reports that North Korea had tested another nuclear weapon in early September.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

I am a Staff Writer for Newsweek's international desk. I report on current events in Russia, the former Soviet Union ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.