On March 11, 1437 AD, Korean royal astrologers saw what they thought was a new star appearing in the night sky. They recorded its position as being in the tail of the constellation of Scorpius, about one degree from the star Zeta Sco or Eta Sco. The brightening was observed for 14 days before fading away.

Now, almost 600 years later, a team of astrophysicists has worked out what was responsible for this cosmic explosion.

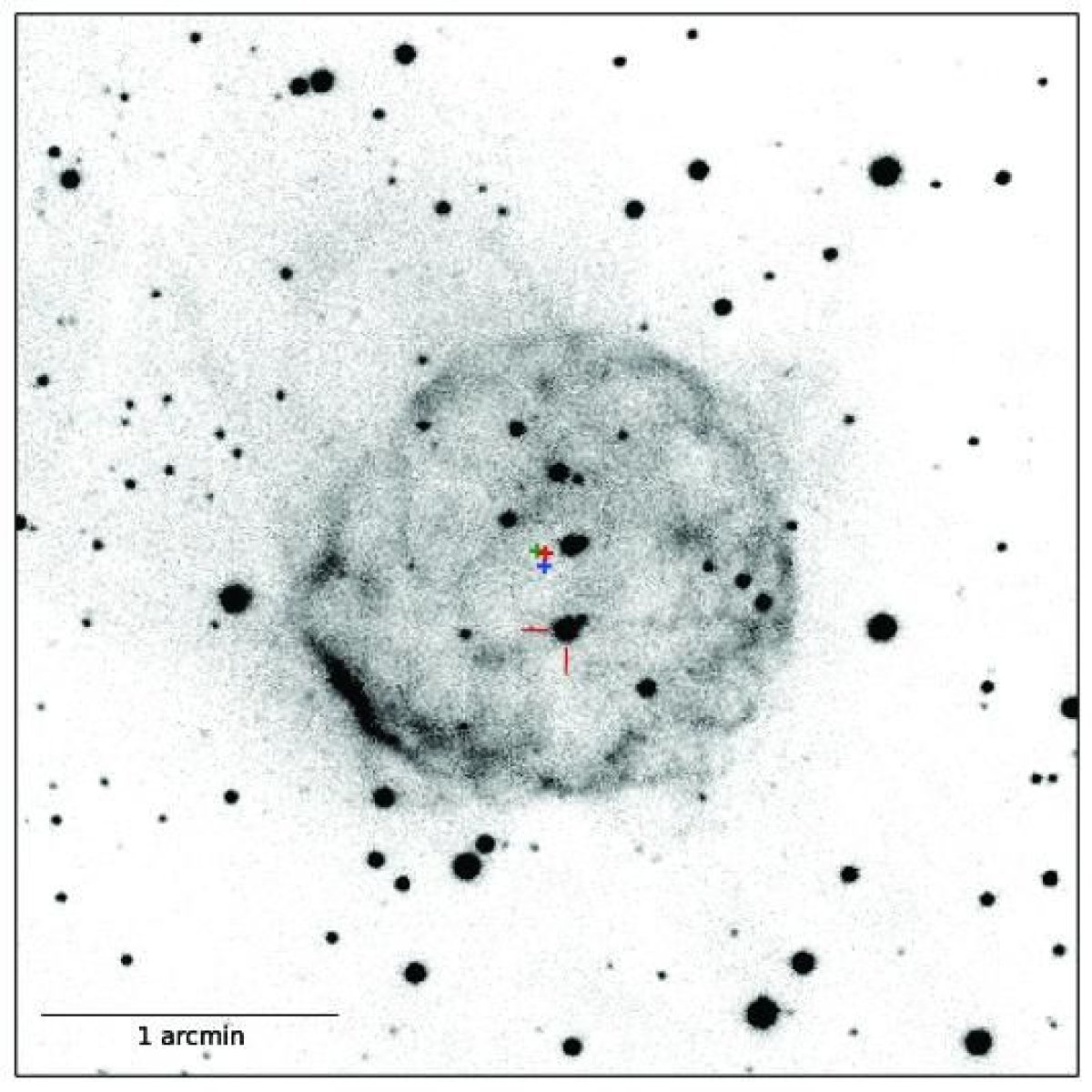

From the original description, the team knew they were looking for a nova eruption—an extremely powerful explosion, where a white dwarf is fed by hydrogen from a nearby star. After around 100,000 years, it has built up so much hydrogen it produces a massive burst, making the star about 300,000 times brighter than our sun for a short period of time.

Which star system was responsible for the 1437 nova eruption was a mystery, however. In a study published in the journal Nature, researchers led by Michael Shara, from the American Museum of Natural History, New York, started looking back at thousands of years' worth of historical records of binary systems that could have been responsible.

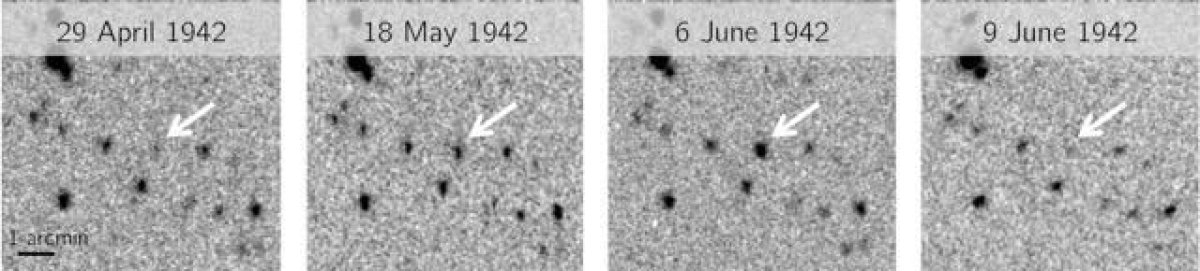

In these records, they were searching for a bright object with a shell of hydrogen surrounding it. By analyzing various plates taken with different telescopes over the past 100 years, along with records from ancient China, Korea and Japan, they were able to narrow down the candidate stars to just one.

"This is the first nova that's ever been recovered with certainty based on the Chinese, Korean, and Japanese records of almost 2,500 years," Shara said in a statement. One plate—taken at the Harvard Observatory station in Peru in 1923, provided the final piece of evidence for identifying the binary system. "With this plate, we could figure out how much the star has moved in the century since the photo was taken," Shara said. "Then we traced it back six centuries, and bingo, there it was, right at the center of our shell. That's the clock, that's what convinced us that it had to be right."

Following the discovery, the team was able to learn more about the binary system, discovering that since the 1437 nova eruption, it had undergone several smaller explosive events knowns as dwarf novas. This is where eruptions are produced but on a much smaller scale, so nowhere near as bright.

Finding dwarf novas coming from the same binary system appears to indicate they work in cycles. Over hundreds and thousands of years, they produce dwarf novas while building up the hydrogen required to produce a massive nova eruption.

"In the same way that an egg, a caterpillar, a pupa, and a butterfly are all life stages of the same organism, we now have strong support for the idea that these binaries are all the same thing seen in different phases of their lives," Shara said. "The real challenge in understanding the evolution of these systems is that unlike watching the egg transform into the eventual butterfly, which can happen in just a month, the lifecycle of a nova is hundreds of thousands of years. We simply haven't been around long enough to see a single complete cycle. The breakthrough was being able to reconcile the 580-year-old Korean recording of this event to the dwarf nova and nova shell that we see in the sky today."

Commenting on the findings in a related Nature article, Steven Shore from the University of Pisa said the study was a "lovely piece of historical scholarship." He said astronomers will now need to find other similar systems that are currently in "temporary retirement," and that the study provides the key to finding them.

"This discovery suggests that cataclysmic variables generate novae for part of the period between successive classical novae, potentially settling a long-standing debate in the field regarding the nature of these explosions," he wrote.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Hannah Osborne is Nesweek's Science Editor, based in London, UK. Hannah joined Newsweek in 2017 from IBTimes UK. She is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.