Racheal Stirling's neck throbbed as the 6 train rumbled over the tracks. It was late afternoon in September 2014, and Stirling was headed uptown from her East Village apartment. She stepped off the subway on 125th Street in East Harlem and trudged toward a boxy brick building, the headquarters of the New York Police Department's Special Victims Division.

She had hoped for a bright, clean office full of relatively friendly detectives, men and women who were eager to help. But when she walked inside, an officer led her down a dark, dingy hallway into a small room with plain white walls. There, she waited nervously, going over what had happened in her mind—details she had filed with her local precinct the day before. Soon, the door opened, and Lukasz Skorzewski, a baby-faced detective in the Special Victims Division, walked in. He sat across the table, and almost immediately, she says, she had a bad feeling. Not only had he not read her complaint, she tells Newsweek, but when he asked her what had happened, he seemed confrontational, brusque.

Three days earlier, according to a statement Stirling later made in court, she had been hanging out at her apartment with Juan Scott. He lived on her block, and the two had been enjoying a "carefree summer fling." But as Stirling, then 26, sat barefoot next to Scott on her bed that evening, he suddenly made a confession: He liked to climb onto his roof to watch naked women through their windows, then find them on the street and ask them out. "Kind of makes you wonder how I found you," said Scott. He then started taking off his clothes and suggested they have sex. Stirling felt uncomfortable. His comments were disturbing, she recalls, and she told him she didn't want to sleep with him.

Enraged, Scott smashed a beer bottle on the floor, the shattered glass blocking her path to the door. He started screaming at her and pinned her down, threatening to rape her. Stirling cried and begged him to stop. At one point, Scott slammed Stirling's head into the wall and shoved his fingers inside her. This is it, she thought. This is how I die.

After hours of Scott screaming and sexually assaulting her, according to Stirling's statement, he apologized and used a broom to clean up the broken glass. Stirling realized her only chance to get away from him was to act as if everything was normal, so she pretended she wanted a cigarette and suggested they go outside to smoke. Once they reached the sidewalk in front of the building, Scott asked for a hug and a kiss; Stirling agreed, hoping to keep him calm. They said goodbye, and as he walked away, she stepped back into her building and locked the door behind her. Later, she went to the hospital and learned she had a broken rib, a sprained hip and a concussion.

As she sat across from Skorzewski at the police station, Stirling's head and hip still hurt. She stared at him, waiting for his response. But he seemed unconvinced by her story, she thought. He told her she should call her attacker to record the conversation and get him to confess to the assault, a standard investigative technique. But the thought of calling Scott was terrifying. During the attack, Scott had threatened to find and rape her whenever he wanted to have sex, and now she was supposed to casually call him up? Skorzewski pressed her, asking, "What are you afraid of?" she recalls in an interview with Newsweek.

Stirling breathed. She swallowed her fear. She picked up her cell, dialed the number. The detective told her to act normally, to avoid conflict. They needed Scott to feel comfortable; she had to act as if she'd like to see him again.

At first, Scott seemed suspicious, but Stirling kept talking, mollifying his concerns. And as the detective listened in, Scott eventually apologized for the assault. Stirling felt relieved. Skorzewski had a confession, she thought, and could now quickly arrest him.

Her relief didn't last. After she hung up the phone, she says, the detective told her the attack was just a misdemeanor, that wouldn't result in any time behind bars. "He's not going to prison for this," Skorzewski said, then tossed her case file to the side of the desk. (Through his lawyer, Skorzewski did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Stirling was stunned. She pleaded with the detective. "If he did this to me, he's definitely going to do it again to the next woman who rejects him," she recalls saying. "He's going to do this again."

'A Long Way to Go'

Six months after dozens of women accused Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein of rape and sexual harassment, thousands of women have come forward on social media and shared their own stories of mistreatment, under the hashtag #MeToo.

Yet only about a quarter of women in the U.S. who are raped report the attack to law enforcement, according to national data from the Department of Justice. Advocates for sexual assault victims say their reluctance is, in part, related to the ways that police investigate sex crimes. In recent years, Justice Department probes have identified several police departments across the country that regularly fail in their handling of rape and sex crime cases. In Baltimore, federal investigators discovered that detectives rarely tried to identify or interview suspects or witnesses, even when women clearly identified them after being raped. In Memphis, Tennessee, police often failed to submit rape kits for testing, according to a retired lieutenant who testified last November as part of an ongoing lawsuit filed by victims.

New York City has similar problems. Stirling is just one of many sexual assault victims who say they experienced poor or careless treatment at the hands of Special Victims detectives. About half of the nearly 700 sexual assault victims whom the nonprofit Crime Victims Treatment Center in New York City helps each year report some kind of negative interaction with the police, like the detectives appearing bored or dismissive or not calling them back for weeks, says Christopher Bromson, the group's executive director. And about 15 percent of those victims report "egregious" treatment, such as a detective saying something like "This wasn't a rape," Bromson says.

A big part of the problem, critics say: Many investigators in the city's Special Victims Division have little to no prior investigative experience; about a third of new recruits come directly from patrol duty, according to a March report by the city's Department of Investigation, the agency that probes internal corruption. Recruits receive just five days of formal specialized training, compared with six to eight weeks of instruction for a motorcycle patrol officer, the watchdog found.

Prosecutors have said those detectives sometimes mistreat victims, close cases too quickly and discourage people from pursuing prosecution. "The detectives were yelling at the victims and saying inappropriate things, such as 'The district attorney is going to make you look like a slut on trial,'" Lisa Friel, a chief of the district attorney's Special Victims Bureau at the time, said in 2009 in a confidential draft of an NYPD memo written about a poorly performing Special Victims detective and obtained by Newsweek. "They also threatened the victims that they're going to lock them up."

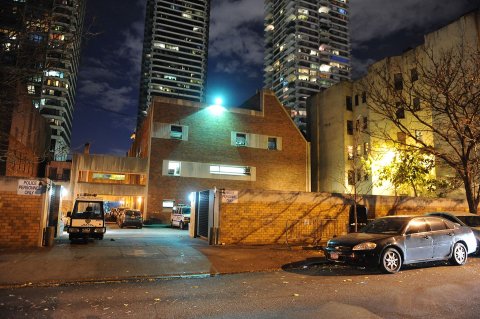

The NYPD says it has undertaken a number of efforts to change the Special Victims Division's culture in recent years, all aimed at treating sexual assault victims with more sensitivity. A special unit now reviews all sex crime complaints, about 8,000 each year, to make sure they're correctly classified as felonies if necessary. Another team investigates cases where police suspect a date rape drug like GHB was involved. The NYPD even moved the Special Victims headquarters from the higher-crime East Harlem location Stirling visited to a calmer spot in the East Village.

In one major reform that began last year, the division began allowing victim advocates to review a sample of random felony cases to help them better understand the process and allow them to weigh in on it. The department also implemented new interviewing training for detectives. This, the NYPD says, is helping it produce better information and evidence from victims without re-traumatizing them. Called forensic experiential trauma interview, or FETI, the technique prioritizes conversation over interrogation, with detectives asking broad questions about what the victim experienced. "It's going to transform the way police interact with victims," Susan Herman, the NYPD's deputy commissioner for collaborative policing, told Newsweek in an interview late last year.

The NYPD is the largest police department in the country, and its practices can have an outsized impact on how U.S. law enforcement deals with rape and sexual violence. "I think we as a police agency are far ahead of most police departments in sexual assault investigative services," Deputy Chief Michael Osgood, who took over as head of the Special Victims Division in 2010 as part of an effort to overhaul it, said in the same interview. "I'd be surprised if any other police departments are superior to us."

Critics say problems remain. The recent Department of Investigation report found the Special Victims Division was severely understaffed, with just 67 detectives working 5,661 cases last year. (That's 20 times the caseload of homicide detectives.) In part to cope with the staffing shortage, the division downgraded "acquaintance" rapes—assaults where the victim knows the attacker—according to the report. NYPD leadership instead directed detectives to prioritize "stranger" rapes and cases that attract more media attention. The report called for the NYPD to overhaul the Special Victims Division and double its number of detectives. (In a statement, the NYPD bashed the report as inaccurate and misleading. It said there are actually 85 Special Victims detectives currently catching cases and maintained that the division's investigators are the best trained in the department. An NYPD spokesman added that the total head count in the division increased by 36 people this year.)

The fallout from the report was swift. The City Council held a hearing April 9 as lawmakers proposed legislation to improve the division. "The criminal justice system is not nearly as responsive to victims as it should be," Terri Poore, policy director at the National Alliance to End Sexual Violence, a policy group in Washington, D.C., told Newsweek in an interview last year. "We have a long way to go." The NYPD's Herman acknowledged as much. "We need to get better," she says.

Stirling—whose story Newsweek corroborated with court records, emails and her contemporaneous notes—couldn't agree more. She says her experience with Skorzewski has led her to believe the NYPD has a deeply rooted problem with how it handles reports of rape and sexual assault. As she puts it: "I followed the rules to a T, and that did nothing for me."

'Call the Cops'

After her meeting with Skorzewski, Stirling, a copywriter, moved into a family friend's apartment in SoHo. She was terrified Scott might return and attack her, and her body broke out in hives from the stress. Every few days, she took a cab to the front door of her apartment so she could sneak in to feed her cat. (She had a roommate, but he often stayed with his boyfriend.)

Stirling hadn't spoken to Scott since she filed charges, but a few weeks later he realized she had reported the attack and began to send her threatening texts. "I will see you eventually," he wrote in a message Stirling provided to Newsweek. "You live on the same block."

Worried for her safety, Stirling pressed Skorzewski to look for Scott at his parents' house on Long Island or at his other relatives' East Village apartments. She begged the detective to put him behind bars. "You're the only person who can help me," she wrote in an email. "The sooner this guy is arrested, the sooner I can regain a sense of normalcy." But the detective never responded, she claims.

On October 8, a little over two weeks after the attack, Stirling moved back into her apartment. She was still afraid, but her injuries hadn't healed and she didn't feel strong enough to move from home to home as a guest. About a week later, around 11 p.m. on October 16, she was getting ready for bed after a long day at work when she heard a loud knock at the door. Her roommate looked out the peephole and spotted Scott. "It's him," her roommate whispered. "Call the cops." Which she did.

Scott stayed in the hallway for about 20 minutes, repeatedly calling and texting her. She answered once, because the number was blocked and she thought it was the police, then hung up when she heard him say, "Please drop the charges." But by the time the patrol officers arrived, about half an hour later, Scott was gone. Stirling told the officers they could probably find him at his apartment down the street. But the officers shrugged, she claims, and declined, saying Special Victims detectives would deal with him in the morning.

Three days passed before Stirling heard from the police again, she says. It was October 19, and a detective called to say Scott was behind bars and she needed to come uptown and identify him. She felt excited, relieved. But the feeling didn't last. When she arrived at the station, the Special Victims detectives told her that Scott had attacked another woman; he had assaulted her only hours after he showed up at Stirling's building. This time, the victim was a stranger. Around 4 a.m. the next morning, he had followed a 20-year-old into her apartment in Manhattan's Stuyvesant Town. Inside the elevator car, he forced her to the ground and pulled up her skirt to assault her with his fingers—just as he had with Stirling three weeks earlier, according to the criminal complaint.

The woman screamed, and residents of the building came out of their apartments to see what was going on. Scott ran, but security cameras captured him fleeing. The next day, a Special Victims detective arrested him at his mother's house on Long Island—the address Stirling says she gave Skorzewski multiple times.

When she arrived at Special Victims headquarters, detectives showed Stirling grainy surveillance photos of the man in the Stuy-Town attack and asked whether he looked like Scott. "Yes," she said. Now that he had attacked a stranger and been caught on tape, the authorities charged Scott with the assault on Stirling, his attack in Stuy-Town and another sexual assault a few months earlier.

The police had finally nabbed the man who had sexually assaulted her. But Stirling didn't feel thankful. She felt angry. They should have arrested him weeks earlier—before he hurt another woman.

"They treated me like I was lying and didn't believe me for an entire month," Stirling says. "It didn't have to be this way."

'Your Credibility Would Be Shot'

As Stirling awaited Scott's trial in early 2016, she began researching how police handle reports of rape and sexual assaults. The results shocked her. And one of the first stories that popped up on Google involved Skorzewski.

"EXCLUSIVE," a New York Daily News headline said. "Married NYPD cop accused of kissing, groping rape victim after booze-filled night in Seattle." "I was like, 'Holy shit, nobody informed me all that was going on!'" Stirling says.

In June 2013, a little over a year before Stirling's assault, a nursing student named Rachel Izzo, then 23, called the NYPD to report she had been raped in Manhattan. The assailant, she claims, was a writer for a television crime drama. Izzo had met him while she was visiting from Seattle. Skorzewski picked up the case. Izzo was back home in Washington state when she made the report, so the detective and his supervisor, Special Victims Lieutenant Adam Lamboy, flew out to interview her.

They met in a small breastfeeding room at Izzo's alma mater, Seattle University. Izzo felt comfortable on campus, and security told them the room was private and unoccupied. Inside, the Special Victims cops listened as she described how the writer had raped her in his apartment after they had dinner together; the writer undressed her even as she told him she wanted to keep her clothes on. "Are you sure you really said no?" Izzo claims Lamboy asked about two hours into the interview. Izzo felt attacked. She shut down and didn't elaborate when the cops asked if she had any questions.

The next day, however, she felt emboldened. She wanted to know how they planned to investigate. Skorzewski asked to chat in person, and after Izzo got off work, the two met to discuss her case. Afterward, the detective asked her to walk with him to a restaurant where Lamboy was having lunch. When they arrived, the latter was drinking at a table outside with his girlfriend and asked Izzo to join them.

She declined, but Lamboy insisted. "It's OK," he said, according to the lawsuit Izzo filed in federal court against both officers and New York City. "We'll protect you." The detectives urged her to order a drink, and over the next 10 hours, they hopped from bar to bar in Seattle's trendy Capitol Hill neighborhood, according to the lawsuit.

Lamboy and Skorzewski got so drunk, the suit alleged, they were cut off and refused service, even as they discussed Izzo's case and other rape investigations in front of her. "You're my favorite victim!" Skorzewski told Izzo.

At some point after midnight, Izzo said she needed to go home. The officers, however, persuaded her to spend the night at their hotel, where Izzo slept on the bed in Skorzewski's room. (He slept on a nearby couch.)

The next morning, Izzo woke up and started watching television, she says. To her surprise, Skorzewski climbed into the bed, touching her and saying he wanted to kiss her, according to her lawsuit. Frightened and confused, she froze. She told him that was inappropriate. He persisted, and she told him she had to keep her clothes on. The detective started laughing, remembering that was what she had told her rapist back in New York City. "Then I just gave up," she says. Skorzewski kissed and fondled her. After a hal- hour, Izzo stood up and went into the bathroom, where she started to cry. (In court documents, Skorzewski denied almost all of the claims Izzo made in her suit; Izzo later settled for $10,000, paid by the city, Lamboy and Skorzewski.)

When she returned to the bedroom, Skorzewski confronted her about what had just happened, Izzo claims. "It can't leave this room," he said, according to her suit. Before leaving for New York the next day, Lamboy was more explicit, telling Izzo that her speaking out about their night drinking together could jeopardize her case. "Your credibility would be shot" if people discovered their night out, she was told, according to the suit. (A lawyer representing Lamboy said the lieutenant didn't know about any intimate contact between Izzo and Skorzewski and learned about that only after he returned to New York City.) Izzo felt crushed.

Over the next few months, Skorzewski texted and called her nearly every day, according to her lawsuit. The two had long conversations about their lives and the cases he was working. Izzo says she knew their continued contact was strange—and she felt he kept in touch to keep her quiet. But after her rape by the man in New York, she was desperate for support, and he was offering it. "[I've] never bonded with a victim like this before," Skorzewski told her.

In October 2013, Izzo says, Skorzewski urged her to fly to New York to stage a call with the man she said raped her to record a confession. During the call, Skorzewski jotted down questions on a notepad for Izzo to ask her attacker. Just hearing her attacker's voice made her feel uneasy, and the attempt to lure him into admitting the attack failed. Afterward, Skorzewski stopped returning her calls, she claims.

Angry and frustrated, she tried his office. A Special Victims detective picked up. Izzo claims the detective told her the division had closed her case and asked her to stop calling—then suggested she hadn't been truthful about the attack in New York. "We don't play games here," Izzo alleges the female detective told her. I'm sorry you had a bad experience, the detective said, "but that does not mean anything criminal happened."

Izzo was despondent, and in April 2014 she reported Skorzewski and Lamboy to the NYPD Internal Affairs Bureau, the unit charged with investigating police misconduct. Eight months later, the Internal Affairs probe confirmed parts of Izzo's complaint, and Lamboy and Skorzewski eventually pleaded guilty to departmental—not criminal— charges of bad conduct with a victim. Both detectives admitted to acting inappropriately with Izzo, while Skorzewski admitted to being intimate with a victim in a case he was working on, according to records filed as exhibits in Izzo's lawsuit.

As Stirling read about Izzo for the first time, she couldn't believe it. Skorzewski had been under investigation for five months when he took her case. How, Stirling wondered, was that ever allowed?

'I'm So Sorry'

In June 2016, Scott pleaded guilty to the three sexual assaults. But Stirling still felt wronged by the NYPD. So as his sentencing approached, she prepared a statement blasting the police for how they handled her case. When she discussed it with the assistant district attorney who prosecuted her case, however, he urged her not to criticize the department. "He said something along the lines of 'We want to focus on how awful Juan Scott's actions were,'" Stirling recalls. "'We don't want the story to be about how the NYPD messed up.'"

She didn't relent. Standing before a judge and a crowded courtroom in downtown Manhattan that November, Stirling read her statement. She talked about the concussion she suffered in the attack, how it made it difficult for her to think clearly or finish her sentences, as well as how Skorzewski made a terrifying experience even worse. "If the police had taken me seriously, this third assault could have been prevented," Stirling told the court. "The system has failed me at every step of the way." The judge sentenced Scott to 14 years in prison.

Two months later, in January 2017, Stirling delivered her story again, this time to NYPD Commissioner James O'Neill. She had come to police headquarters along with victim advocates who wanted to press the department to improve how it investigates sexual assault cases. Sitting at a conference table, she recounted how Skorzewski had ignored her pleas for help. According to the advocates, O'Neill was dismayed and immediately apologized. "I'm so sorry this happened to you," he said. The advocates said O'Neill told them he believed the FETI training, along with other reforms, would help with the problems they raised. (The NYPD declined to comment on the meeting.)

For Stirling, though, the department's response seemed more talk than action. The NYPD had ultimately placed Skorzewski on "dismissal probation," a punishment in which an employee is nominally dismissed but kept on the job for one year, according to police records filed in Izzo's lawsuit. "When the year is over, so is the probation," BuzzFeed reported in a recent investigation that criticized the practice. Today, Skorzewski is no longer a detective investigating sex crimes, but he remains an officer in the NYPD.

"You'd think the NYPD would want to distance themselves [from Skorzewski]," Stirling says. "He's a liability to their name."

'Our Names Are the Same'

Nearly three years after her assault, Stirling received an email from Noah Hurowitz, a reporter who had covered Scott's sentencing for the website DNAinfo. Stirling had contacted him months earlier to thank him for his coverage but hadn't heard back. Now, he had a surprising offer: Would Stirling like to meet Izzo? The reporter had interviewed her for a piece about how the NYPD investigates rapes, and Izzo—who knew of Stirling's case—had asked for an introduction.

Stirling agreed, and Hurowitz connected them via email. The two women exchanged messages and discovered they had a lot in common: "Our names are the same," Stirling recalls thinking. "We're both from Washington state, we were screwed over by the same detective, and we both love cats."

They were both living in New York City as well. So on a cool spring day in May 2017, Stirling and Izzo met for the first time in Cobble Hill, a quiet, fashionable neighborhood in Brooklyn. They bought tea at a coffee shop and sipped it as they walked a few blocks east to Boerum Park. They eventually sat down on a bench and talked about what they had been through.

Both recall how Skorzewski hadn't updated them on their cases after their initial reports. Izzo gets angry when she sees news stories about rape or sexual assault, and Stirling had terrifying flashbacks about her attack and nightmares where Scott got out of jail, only to hurt her again as police stood by and did nothing. It felt good, they thought, to have someone who understood what the other was going through. "I hate using this word, but I was relieved to have a 'rape buddy,'" Stirling says. "She understood me in a way that no one else could."

Izzo agrees, adding that many victims she's met are so immersed in their attack, they can't focus on anything else. Not Stirling. "I got this air from her that she's really strong and badass and didn't act like a victim at all," Izzo said. "I really related to that." After about an hour together, the women said goodbye.

Today, they text back and forth at least once a month, trading news stories about rape cases and leaning on each other when they have a hard day. (The revelations about sexual abuse by a U.S. Gymnastics team doctor were especially upsetting to Izzo, who competed in the sport when she was younger.) Together, they say, they found the strength to call out the NYPD and push for changes so other women are treated better.

As Izzo puts it, "We didn't let it kill us."