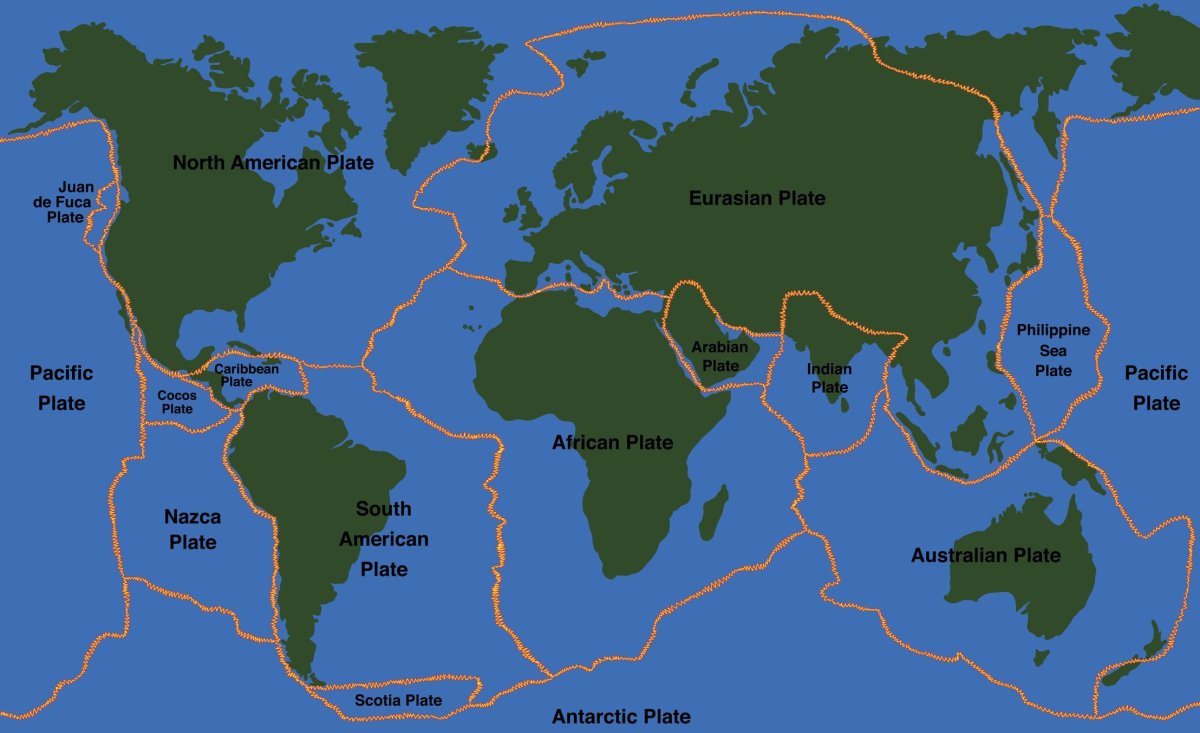

Three times more water is being sucked into Earth's interior through its subduction zones than was previously thought, scientists have discovered. These huge fissures that scar the planet's surface appear at the boundaries of tectonic plates. When they collide, they drag water down miles and miles, locking it up inside the rocks in the plates.

Understanding the global water cycle is hugely important—water covers most of the planet and is necessary to the survival of all life on Earth. We know there are vast quantities of water locked up inside Earth. Research published last year indicates there is as much water in Earth's mantle as there is in all the oceans combined. After being pulled in, the water is eventually spewed back out as water vapor during volcanic eruptions hundreds of miles away.

Scientists know subduction is the only mechanism through which water is taken into the planet's interior—yet our understanding of it is fairly limited.

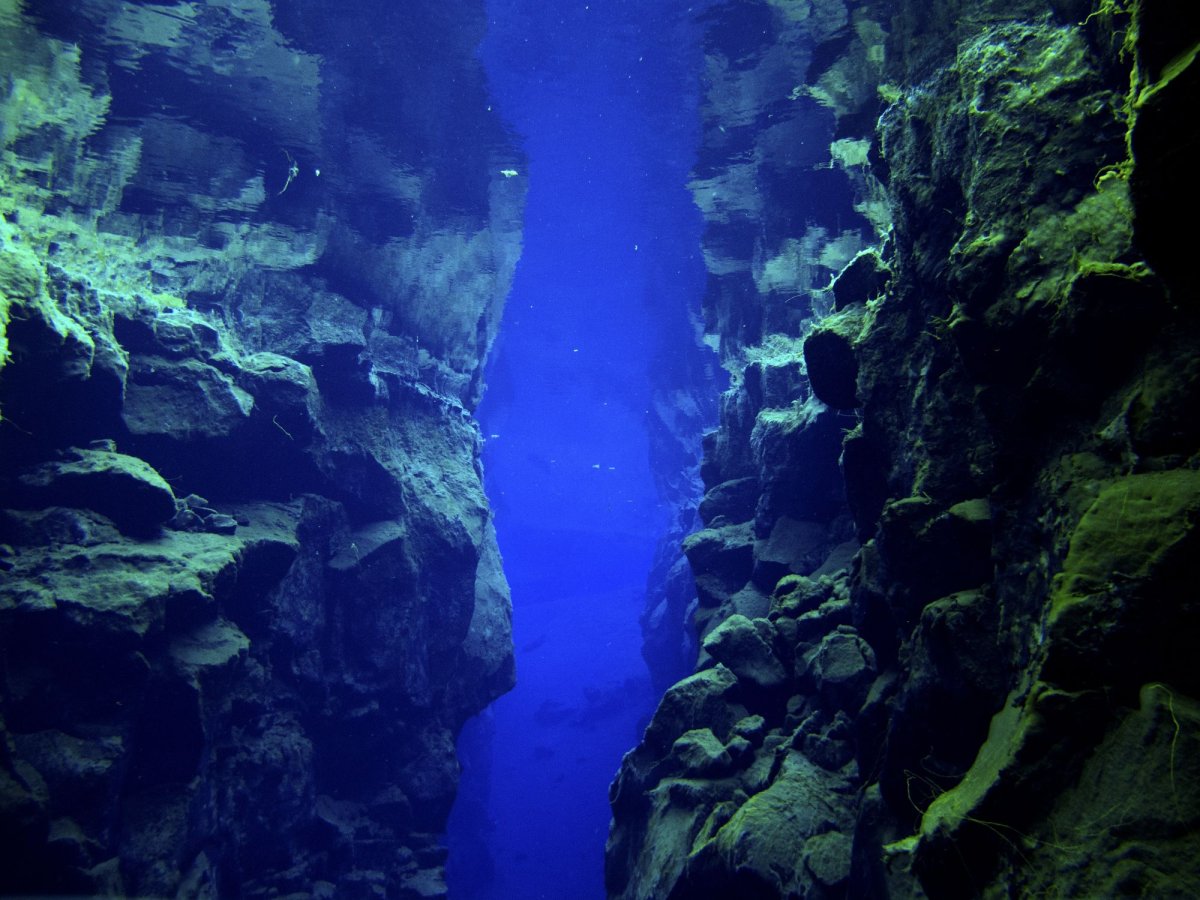

Douglas Wiens and colleagues from Washington University in St Louis have now studied water subduction at the Mariana Trench in the Pacific Ocean. This is the deepest natural point on Earth, extending down almost seven miles below sea level. It is part of the subduction system where the Pacific Plate is thrust beneath the Mariana Plate.

When water runs down into Earth's crust along the fault lines, it gets trapped. At certain temperatures and pressures, chemical reactions mean the liquid water becomes "wet rocks"—a hydrous mineral that then forms part of the tectonic plate. These wet rocks are then pushed deeper and deeper into the mantle.

In their study published in the journal Nature, the team establishes how much water is being pulled into Earth's interior through the Mariana Trench in this way. They gathered data using 19 seismographs dotted across the trench, listening out to everything from ambient noise to underwater earthquakes. With this, they were able to build up a picture of the type of rocks that lie up to 20 miles beneath the sea floor. The speed at which the seismic waves travel indicates how much water the rocks could hold.

Findings showed the amount of water held in the rocks was far higher than initially thought—up to four times previous estimates. If we apply these findings to subduction zones around the world, it means around three times more water is being pulled into Earth's interior in this way.

Wiens said that one caveat of the research is assuming the Mariana Trench is representative of other trenches. However, he said it does not appear to be unusual in terms of its intensity or how much the plate faults. "In fact, some other subduction zones such as Tonga seem to have more faulting than Mariana, with larger fault throws on the seafloor," he told Newsweek. "This suggests that, if anything, Mariana might have less water than Tonga."

If correct, the findings mean there is a big inconsistency between how much water is being absorbed and how much is being expelled out. "Through geological time, the amount of water in the Earth's interior would increase, and the amount on the Earth's surface would decrease," Wiens said. "That is inconsistent with the observations that the oceans have been present in the current form for at least for the last 550 million years."

Researchers believe far more water is being expelled through volcanic eruptions than previously thought—and this is something that will need to be addressed when it comes to understanding the global water cycle.

"Water is key to understanding how our planet has evolved through geological time," Wiens said. "Many studies suggest that the presence of abundant water on the Earth's surface and in the Earth's mantle is what allows plate tectonics to occur on the Earth. Understanding how water interacts with terrestrial planets is also key to understanding how likely it is that planets—such as exoplanets—are habitable."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Hannah Osborne is Nesweek's Science Editor, based in London, UK. Hannah joined Newsweek in 2017 from IBTimes UK. She is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.