An octopus in the deep sea was observed brooding its eggs for four-and-a-half years, longer than any other known animal, a paper published on Wednesday in the Public Library of Science, or PLOS ONE, revealed.

Researchers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute found a female octopus 4600 feet below the ocean surface clinging to a rocky ledge while guarding a clutch of eggs in May 2007. The scientists went back to the site off central California 18 times over the next four-and-a-half years, and found the Graneledone boreopacifica octopus, identified by distinctive scars on her body, in the same place.

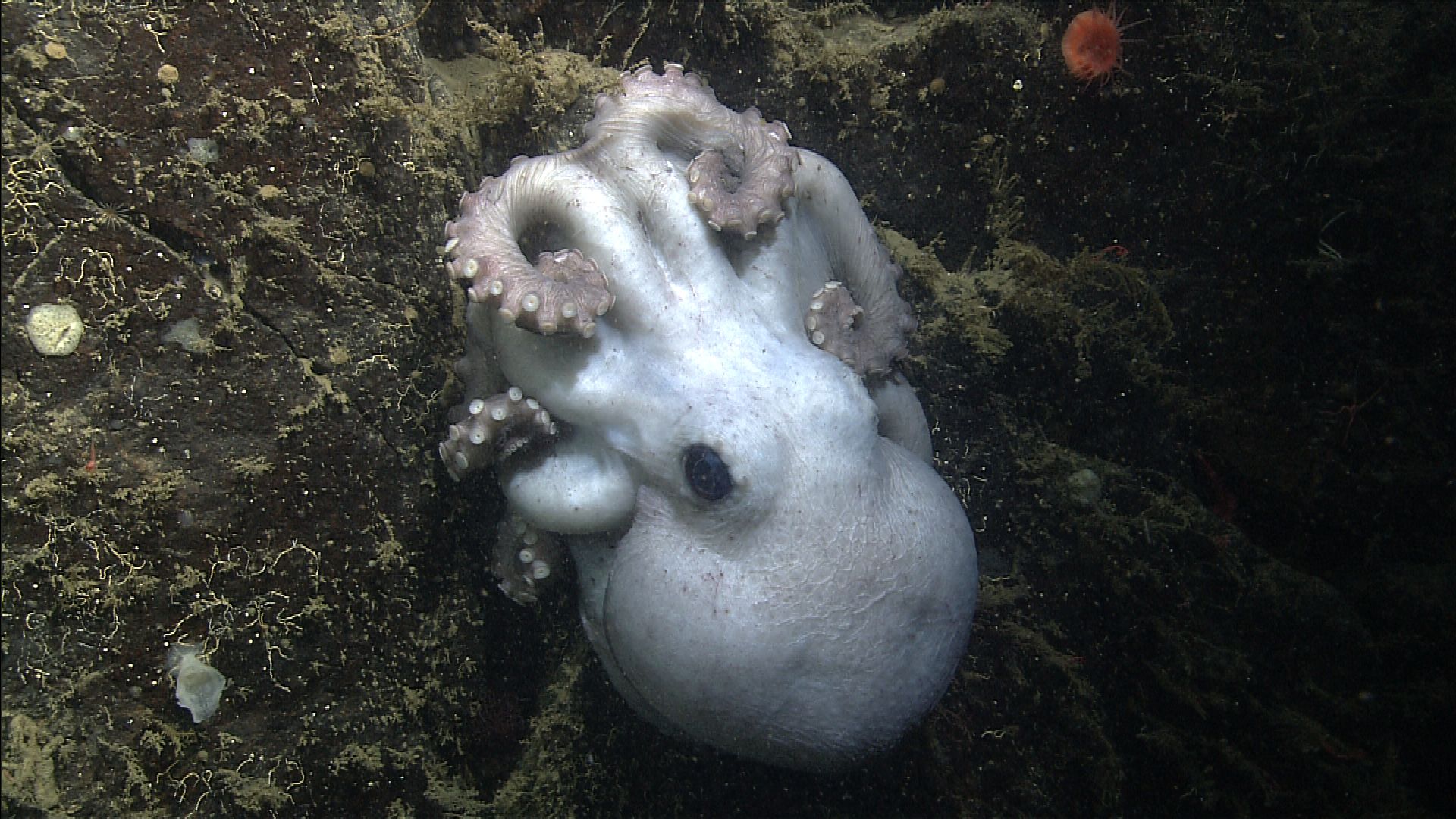

Time went by and the octopus, whom the scientists referred lovingly to as Octomom, "occasionally shifted her position slightly, or uncurled and lifted one or two arms," said the study, but, "the female always remained centered over the clutch of eggs." Overtime, the octopus lost weight, became flaccid and weak-looking. She went from a pallid purple to a pale, almost white hue.

The researchers did not see her eat; in fact, when shrimp or crab came near her, the octopus pushed them away. When the scientists offered her pieces of crab using a remotely operated vehicle, she ignored them.

The eggs, in the meantime, grew larger; and their resident young octopuses became visible to researchers. The mother octopus had to continuously bathe the tear-drop-shaped, olive-sized eggs in fresh, oxygenated seawater and keep them clean.

"These octopuses are at the very extreme end of the spectrum where they are putting a lot of parental investment to make sure that their offspring are competitive when they hatch," said Brad Seibel, professor of marine biology at the University of Rhode Island and one of the main researchers in the study.

Bruce Robison, who led the team of researchers, sent out photographs of the mother octopus to his colleagues after each dive. "It was sort of like getting pictures of your kids after a while," said Seibel with a laugh, referring to the scientist's growing fascination with the octopus and her brood.

The mother octopus was last seen in September 2011, after 53 months of observation. When the scientists returned a month later, the brooding octopus was gone and the clutch size was revealed to have been between 155 and 165 eggs. Most female octopuses die after laying their first and only set of eggs.

"Hatchlings of G. boreopacifica are the largest and most developmentally advanced coleoid cephalopod hatchlings known to date," said the paper, which indicated that this octopus is one of the most abundant deep-living octopods in the eastern North Pacific. Cephalopods are a group that includes squids and their relatives. "They emerge as virtual miniature adults, without a pelagic juvenile phase," the paper concluded.

The longest octopus brooding known to the authors of the paper prior to this was 14 months at 7 degrees Celsius.

How did the mother octopus survive so long this time? Low water temperature, low metabolic demand due to inactivity and the reduced presence of predators at such depths helped. But, Seibel admitted, these findings indicate that scientists still have a lot to learn about the deep sea.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Karla Zabludovsky covers Latin America for Newsweek. Previously, she reported for the New York Times from Mexico, covering regional politics, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.