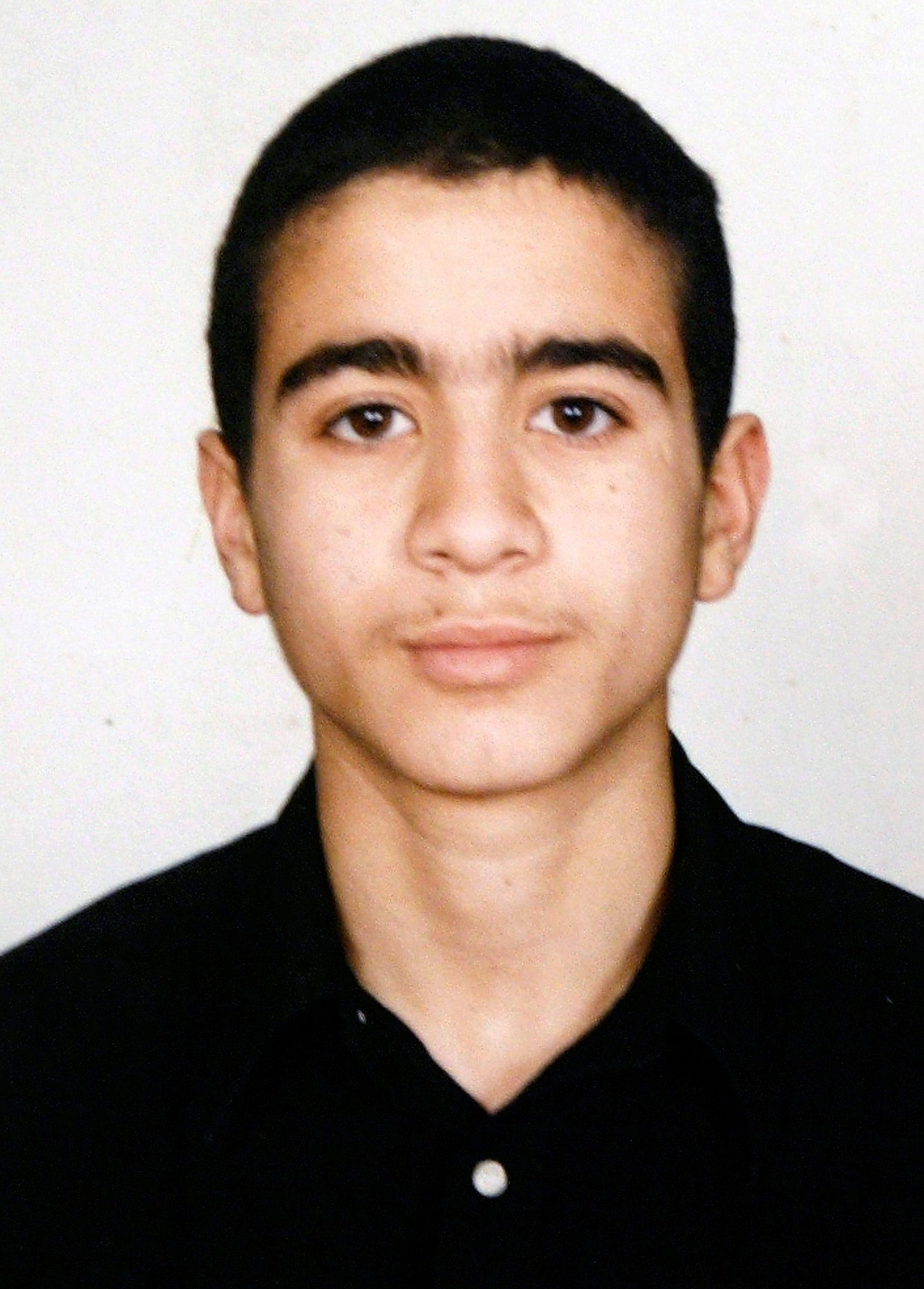

The Canadian government's formal apology and reported CAD$10.5million ($7.7million) compensation payment to Canadian citizen Omar Khadr, alleged former child soldier affiliated with Al-Qaeda and one of Guantánamo Bay's youngest ever detainees, has sharply polarized public opinion.

While critics angrily denounced the pay-out to Canada's "poster boy for terrorism," others saw a vindication of Khadr's struggle to uphold his constitutional rights, and a damning indictment of some of the most glaring abuses of the war on terror.

As the horrific exploitation of children by Islamic State, Boko Haram and other armed groups draws increasing global condemnation, Khadr's case brings the challenge of responding to the use of child soldiers into timely focus.

According to U.S. allegations, Khadr's father Ahmed, who took him to Afghanistan, introduced him to Al-Qaeda leaders at age 10, and sent him for military training at 15 and into the battlefield shortly afterwards, making him a child soldier under national and international law.

In 2002 at age 15, Khadr was captured in Afghanistan by U.S. forces after a firefight, in which he allegedly threw a grenade that killed U.S. Army Sergeant Christopher Speer. Khadr was seriously wounded and transferred to Guantánamo, where he was held for a decade.

As a lawyer appointed to represent Khadr said in 2010: "He was there [Afghanistan] because his father told him to go there. He was there because Ahmed Khadr hated his enemies more than he loved his son."

Khadr was a vulnerable child who was callously exploited by the people who should have protected him.

Whatever else Khadr is alleged to have done, he is first and foremost a victim. The notion that children are particularly vulnerable and therefore in need of special protection, especially in situations of armed conflict, is a hallmark of justice and child protection systems the world over.

International human rights law recognizes that due to their immaturity and relative under-development, children alleged to have committed crimes deserve to be treated with special care, taking into account their age, capacity for rehabilitation and lower degree of culpability. Any justice system dealing with children must have their best interests at its heart.

However, in Omar Khadr's case, the U.S. flouted its obligations under national and international juvenile justice standards, subjecting him to years of unlawful detention, abusive interrogation and unfair trial in one of the most notoriously abusive detention centres in the world.

Under international law, children can only be detained as a last resort and for the shortest appropriate time, and their cases must be dealt with promptly. They must be held separately from adults, allowed contact with their families, granted access to a lawyer and be able to challenge the legality of their detention. They have an inalienable right not to be tortured or held arbitrarily.

Khadr was detained with adults, held for over two years before having access to a lawyer, and for more than three years before he was charged by a military commission that the U.S. Supreme Court later judged to have violated U.S. law and the Geneva Conventions.

While in Guantánamo, Khadr was subjected to sleep deprivation and held in prolonged solitary confinement. He told his lawyers that interrogators shackled him in painful positions, threatened him with rape, and used him as a "human mop" after he urinated on the floor during one interrogation session.

The U.S. is primarily responsible for the treatment of Khadr. But Canadian officials cannot escape their share of responsibility. It was the collusion of Canadian intelligence officials in Khadr's mistreatment that the Canadian Supreme Court ruled had offended "the most basic Canadian standards about the treatment of detained youth suspects."

In 2010 Khadr accepted a plea bargain, confessing to five charges including murder, providing material support for terrorism, and spying. Under the deal, Khadr was transferred to Canadian custody in 2012 and was released on bail in 2015. Khadr has since said that his guilty plea was entered under duress and is challenging his conviction in the U.S.

Khadr's case serves as a reminder that child soldiers are first and foremost victims of grave abuses of human rights. National authorities must prioritize their rehabilitation and reintegration, while holding those who recruited them to account. If they choose to prosecute former child soldiers, including those accused of terrorism offenses, they must strike a delicate balance between ensuring accountability for their actions as alleged perpetrators and protecting their fundamental human rights as victims.

In Khadr's case, an egregious failure to do so has only served to add one grave injustice to another, leading to a lengthy and divisive miscarriage of justice. No child exploited in armed conflict should ever be treated this way again.

Tim Molyneux is a programme manager at Child Soldiers International, a human rights organisation that seeks to end the military recruitment of all children.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.