Many say the opioid crisis that has killed more than 183,000 Americans since 1999 is driven by crooked pharmaceutical executives who have done just about everything, legal or otherwise, to convince the public that opioid painkillers are safe. Even President Donald Trump, who recently declared the epidemic a public health emergency, said companies that make the potent and highly addictive painkillers are responsible for the surge in deaths.

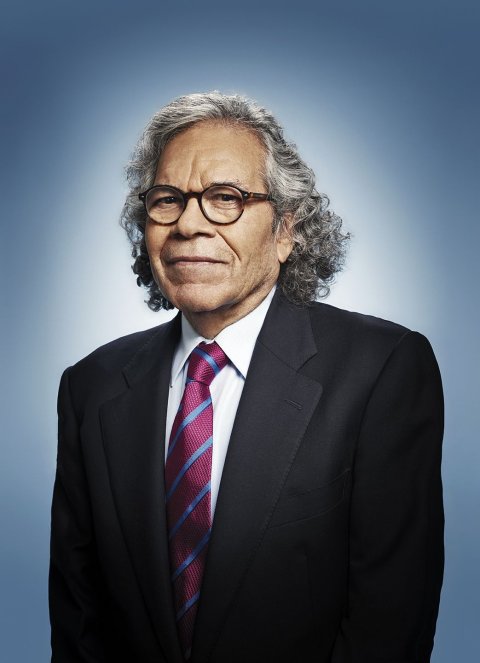

Fentanyl is one of the most dangerous opioids on the market, 50 times more potent than heroin. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that overdoses on this synthetic opioid have increased 540 percent in the past three years, and many say the drug is responsible for the current epidemic. Insys Therapeutics, one of the companies that produce a form of fentanyl, is now mired in an ugly legal battle after multiple executives—including its founder, John Kapoor—were arrested on conspiracy charges in late October. Attorneys general in New Jersey, Arizona, Oregon, Illinois and Massachusetts have filed lawsuits claiming the company plotted to illegally boost sales of its drugs. In all of the lawsuits, Insys is charged with lying to insurance companies, fabricating information about patients and providing incentives to physicians to prescribe the drug.

Insys Therapeutics produces Subsys, a powerful fentanyl-based liquid that earned approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2012 specifically for use by cancer patients with pain that doesn't respond to other painkillers—what's known as "breakthrough cancer pain." Subsys is a fast-acting spray used under the tongue; the mucous membranes beneath the tongue have an abundance of capillaries, so the medication is absorbed directly into the bloodstream without needing to go through your digestive system. This delivery method is highly effective, but it means that overdosing on Subsys is far too easy—and possibly just a few accidental sprays away.

Ongoing federal investigations suggest Insys ran an elaborate scheme to push the drug on non-cancer patients—what's called "off-label use"—despite the fact that the company has not submitted clinical data to prove Subsys is safe and effective to manage pain not related to cancer. The U.S. Attorney's Office in the District of Massachusetts charged Kapoor with "leading a nationwide conspiracy to profit by using bribes and fraud to cause the illegal distribution of a fentanyl spray." The charges include racketeering, mail and wire fraud, and violation of a federal law passed in 2014 (known as the Anti-Kickback Statute) that prevents drug companies from providing large incentives to physicians for prescribing their drugs. Kapoor resigned from the company's board of directors in late October, but said in a statement, "I am confident that I have committed no crimes and believe I will be fully vindicated." (He pleaded not guilty at his arraignment in Boston on November 16.)

Many details of how Insys pushed its drug came to light through a congressional investigation led by Democratic Senator Claire McCaskill of Missouri, a ranking member of the U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. In September, the committee—chaired by Wisconsin Republican Ron Johnson—published the first of what her staff says will likely be several reports on the unethical sales and marketing practices of companies that produce opioid drugs. It laid out how Insys created a separate department to convince insurance companies to sign off on coverage of the drug for patients who weren't authorized to take it. These employees posed as representatives from the doctors' offices of patients who were prescribed the medication.

In response to the opioid crisis, the committee has issued requests for documents from five companies that produce the majority of the supply of opioid prescription painkillers in the U.S.—Purdue Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., Insys, Depomed and Mylan. Insys was the first subjected to McCaskill's scrutiny. She says Insys has followed in the tradition of the unethical marketing and sales practices developed in the 1990s by Purdue, which told physicians that pain is undertreated in the U.S., that opioids were the best way to treat them, and that the drugs aren't addictive. "As it turns out, these messages were exaggerations at best and outright lies at worst," she said during a roundtable discussion about her report in September.

All of these companies have settled lawsuits about such practices or have lawsuits pending. Purdue Pharmaceuticals—maker of OxyContin—reached a number of unprecedented settlements, including one in 2007 that involved 26 states. Since then, the lawsuits against opioid manufacturers have continued to pile up. There are lawsuits against opioid makers in just about every state, prompting many experts to suggest that the legal battle against the prescription painkiller epidemic is starting to look a lot like the late 1990s fight against Big Tobacco.

Subsequent reports, such as one from Reuters, suggest some 80 Insys employees engaged in various schemes to get the medication into the hands of more patients who didn't need them.

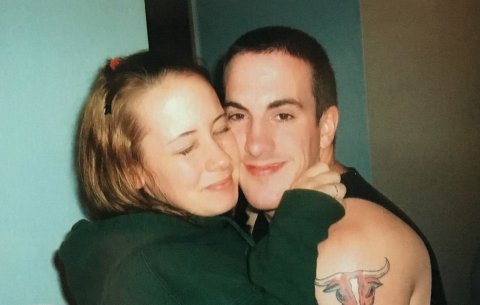

Sarah Fuller was one of those unfortunate people, says her mother, Deborah. The 32-year-old died of a Subsys overdose in March 2016, but she never had cancer. The family is now suing Insys. Sarah had suffered from fibromyalgia and chronic pain related to two automobile accidents some 10 years before.

Deborah barely knew anything about fentanyl until after her daughter's death, when she began going through Sarah's belongings. That's where she found the pharmaceutical pamphlet Sarah had been given during one of the many appointments with the doctor who wrote her Subsys prescription. Deborah read the pamphlet cover-to-cover, and recalls that when she finished reading she was mostly confused, since it was made clear in the information that the drug was only for patients with cancer.

Though it would be months before the family received the results of Sarah's toxicology report, Deborah felt she already knew the drug had killed her daughter. "When I got into what it really is and the dangers of the drug, I thought, Why in the name of God would they prescribe that to her?" she tells Newsweek. "She was so not at all a candidate for the drug."

She believes Sarah was, however, an ideal target for doctors to push off-label use of Subsys. Like most of the 100 million Americans who suffer from debilitating, chronic pain, Sarah desperately wanted to make it stop. "She would call me and say, 'I hurt all over,'" says Deborah. While the pamphlet Deborah found listed the risks of the drug, the language was hard to understand and not written for patients, especially patients like Sarah who, her mother says, had suffered with lifelong learning disabilities and was prepared to try just about anything to get through the day without hurting.

Deborah says her daughter was also eager to stop taking Lyrica, which another doctor had prescribed to manage her fibromyalgia. The drug is known to cause significant weight gain; Sarah added 100 pounds to her 5-foot-3-inch frame while taking it. Her mother says her daughter longed to lose weight in time for her wedding, which would have been this past August.

Sarah had initially sought out a new doctor to find a way to treat her pain without medication. Her mother said she had a history of prescription painkiller use that had landed her in the hospital before. This time she wanted to manage her pain without any prescriptions—possibly with physical therapy or even surgery. But the new doctor began prescribing opioids anyway. Before putting Sarah on Subsys, her doctor prescribed other painkillers, including OxyContin and Percocet. This would show the insurance company that Sarah had tried the less potent and cheaper options—called "step therapy"—but was still experiencing pain. Investigations into Insys show this was a standard protocol of doctors who needed to give the impression to an insurance company that the other prescription painkillers weren't working for the patient. In order for a doctor to receive kickbacks from Insys, insurance companies would need to approve prescription requests for Subsys, which costs thousands of dollars per month. In Sarah's case, Medicare paid as much as $24,000 per month for her Subsys prescription, according to documents collected by the family's lawyer after her death. The drug is far more expensive than other popular painkillers. According to the family attorney's records, a prescription for OxyContin at a CVS pharmacy costs a little more than $250 per month. Her patient records from every visit to the doctor didn't document any changes in her pain, even when she was taking Subsys.

Sarah's fiancé says Subsys initially "seemed like a miracle drug." But soon he noticed changes in her; she became more withdrawn and lethargic. She complained of sleepiness, dizziness and weakness, all side effects of the medication. Over a period of more than a year, Sarah began spending an increasing amount of time at home, says Deborah. She stayed in her bed with shades drawn so her bedroom was pitch black. Unless Sarah had to work or was going out for dinner with her fiancé, she was at home in her pajamas, most likely sleeping. "Two weeks before she died [from the overdose] she kept saying 'I feel like I'm dying,'" says her mother. "And I said, 'You need to get off of this stuff. All of it.'"

Months later, Sarah's toxicology report revealed she had higher-than-lethal levels of fentanyl in her blood, suggesting that she had been prescribed a higher dose than she should be taking. The family's attorney says Sarah's doctor continued to increase the Subsys dose over time. The toxicology report also suggested that the Subsys had interacted with Xanax, another medication prescribed by the same doctor to help her sleep. Using both drugs together can be deadly. (The Fuller family recently reached a confidential settlement with Sarah's doctor, according to their attorney.)

The family's attorney obtained an audio recording of a call between an Insys employee and a representative from Sarah's insurance company's pharmaceutical service to get prior authorization for her Subsys prescription. The Insys employee said she worked "with" Sarah's doctor. She also misrepresented Sarah's condition, claiming she suffered from breakthrough cancer pain. The Insys representative also said other drugs, like OxyContin, had "an inadequate analgesic effect" and the "patient is opioid tolerant" and therefore needed Subsys. The family attorney said there were no notes in her medical records to document changes in her pain.

"They lied so they could make their money," says Deborah about the phone call.

After Sarah's death, Deborah also learned the doctor's office had arranged an in-person meeting for Sarah with an Insys pharmaceutical representative in order to "educate" her about the drug. At the meeting, the pharmaceutical representative showed Sarah how to use Subsys. Pharma reps don't typically meet with patients, a practice that is established to be unethical, at best.

Many of the details from Sarah's case appeared to be common practice for Insys. Over the summer, for example, Anthem health insurance filed a lawsuit against the company, claiming that half of the patients on its insurance plan using Subsys were never diagnosed with cancer.

Insys declined to comment on Sarah's case, which is still pending, but it released a statement in September in response to ongoing accusations, insisting it has changed its business practices, and that employees are no longer communicating directly with insurance companies.

But Insys denies its product is in any way responsible for the uptick of overdose deaths from fentanyl. "It's inaccurate and misleading to suggest that Subsys has contributed to the abuse of illicit synthetic fentanyl," according to the statement, which added that the opioid crisis began more than 15 years ago, while Subsys has only been available since 2012.

While it's true that Insys isn't the only company producing fentanyl-based painkillers, the indictment of so many top executives is unprecedented in this case. Paying fines for causing addiction and death is no longer enough. There's clearly more pain coming for everyone in this business.