Toward the end of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, the best-selling book and now an HBO movie, a woman stands in a science lab, holding in her hands a frozen vial. "She's cold," says Deborah Lacks, played by Oprah Winfrey. She says that because the vial contains cells directly descended from tissue taken from Deborah's mother more than 50 years earlier. For Deborah, holding it is like holding her mother, who died when she was just 2. "You famous," she says to the vial. "Just nobody knows it."

Nobody knew it because nobody was told. Medical research has long followed the principle of anonymity. Tissue removed during surgery or other procedures can be examined, shared, discussed and put through all manner of poking and prodding without the original owner's consent, as long as the identity is stripped from the sample. Even if the cells lead to lifesaving vaccines and medications, the person they were taken from never needs to be disclosed. That's the law.

But in Immortal, that tissue, that bit of a woman's body, is more than a research specimen. For a daughter desperate to know more about her long-deceased mother, holding frozen cells derived from a cancer-ridden cervix is "as close as she would ever come," explains Winfrey. And to get even that close, she had to brave confrontations with medical authorities, racism, her family history and her own troubled psychology.

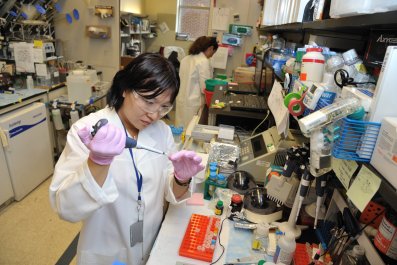

Rebecca Skloot wove three inextricably linked threads into her nonfiction page-turner, which has sold more than 2.5 million copies since it was published in 2010. The movie, which premieres April 22, tells an abbreviated version of the same narrative. First comes the story of Henrietta, a black woman from Baltimore who died of cervical cancer in 1951 at age 31. Scientists had long been searching for human cells that would continue replicating outside a body, which would allow them to experiment directly on human cells, a crucial step for medical progress. For years, doctors removed tissue from patients to see if their cells possessed that magic property.

Related: The best books about cancer

Henrietta's did—and that phenomenon changed the world, starting with the 1952 creation of a polio vaccine. The ability to cultivate Henrietta's cells in petri dishes transformed every inch of the medical research field. The progress we've made against tuberculosis, many infectious diseases, cancer, infertility and other serious conditions can be traced back to Henrietta's cells. They were also the first to be cloned and have led to a vital understanding about how these building blocks of life grow and die.

"Deborah, there isn't a person alive who hasn't benefited from your mother's cells," Skloot, played by Rose Byrne, tells Winfrey's character early in their relationship. Skloot, a young science journalist trying to unearth Henrietta's story, is not only the book's author but also a central part of the story it tells. But in the global distribution of Henrietta's immortal cells and the ensuing discoveries, she was forgotten. The doctors who'd treated Henrietta at Johns Hopkins Hospital called her cells "HeLa," refusing to attach her full name, ostensibly to protect her and her family's privacy. Her children knew nothing of their mother's extraordinary role in medicine until 1975. As they slowly came to understand the significance of their mother's cells, they questioned why they were excluded from that knowledge—as well as from the profits from the many new medicines HeLa led to.

Deborah just wants to know her mother, and that yearning brings her to meet with Skloot, who knows that getting the story hinges on access to the Lacks family. But having been ignored by academics and dissuaded by family—some wanted monetary compensation from the discoveries HeLa enabled, and some worried the pursuit would worsen her fragile mental health—Deborah sometimes trusts Skloot and sometimes is wary of her. "I wanna learn everything I can about my mama's cells," Winfrey's Deborah tells Skloot. "I'm tired of wanting to know and hiding." Minutes later, she is snatching away the envelope containing Henrietta's medical records that she'd just given Skloot. "I don't know who to trust," she says. She walks away in a burst of anger, the first of many such outbursts during her times with Skloot. "She's feeling lied to and thinking about all the times she's been betrayed," says Winfrey, who was also the film's executive producer.

Their races—Deborah is black, Skloot is white—heighten the tension between the two women, as does the racism Deborah encounters as she travels with Skloot to track down her family's history. For George C. Wolfe, who wrote the screenplay and directed the movie, portraying that racial dimension required understatement. "It's in the DNA of our country," says Wolfe, "and it plays out in very subtle dynamics."

In one key scene, Deborah asks a psychiatric hospital employee for information about her sister, who'd been committed there as a child. The employee ignores her, responding only to Skloot. For the real-life Skloot, that moment, some version of which happened repeatedly in the 10 years she and Deborah researched this story, was revelatory. "I'd never thought of myself as privileged," she says, "but working on this story, I realized that my skin color gets me access to things."

In Deborah, Winfrey saw the acceptance that often results from unrelenting discrimination. She cites a moment in the film when Deborah tells Skloot, "Go ahead on, girl, keep on being white," recognizing that Skloot could get answers that she never would. Their dependence on each other—Skloot needed Deborah to get to Henrietta, and Deborah needed Skloot to learn about HeLa—slowly becomes something more. "They became friends in a way that she'd never anticipated," says Winfrey. "She found great comfort from Rebecca."

But finding comfort also meant unburdening herself of the tormenting memories of child abuse suffered at the hands of the aunt who raised Deborah and her brother after their mother died. That release finally comes during a visit to Virginia, where Henrietta, a tobacco farmer, was raised. In the home, a former slave cabin in Atlanta restored for the movie, Deborah, now in her 50s, reveals the horrors she endured to Skloot.

Accessing the emotions necessary to play that scene proved challenging for Winfrey. Her own history of abuse is widely known, but she found that connection wasn't enough. "I no longer had a charge from my own personal abuse," she says. "So I listened to other people's stories." On her way to shoot the scene in the slave cabin, Winfrey called someone she refers to as one of her daughters, a student from a school Winfrey founded in South Africa who now attends college in the U.S. Winfrey knew she had been beaten by her aunt but had long been silent on the matter. Winfrey asked the young woman if she would share her story. "And I will do that scene in honor of you," Winfrey told her.

In the scene, Winfrey's agonizing portrayal embodies at once a child's cry for love and an adult's defiance against a crime she had no power to prevent. Winfrey says the young woman who confided in her was also strengthened by the exchange. "It ended up cracking her open to the point where she was willing to have therapy about it," says Winfrey. "She had not been willing to talk about it before."

Winfrey originally had no intention of playing Deborah, who battles anxiety, depression, rage and other extreme mental conditions. "I didn't want to take on that space," says Winfrey. "Not a way to spend your summer." But Wolfe wanted her. "There's an incredible ferocity to Oprah that Deborah also has," he says. Winfrey remembered her friend, actress Audra McDonald, urging her to find a way to work with Wolfe at any cost. "'It will change you,'" Winfrey recalls McDonald telling her. "And she was right."

Playing Deborah, who died in 2009, was "the most challenging role I've ever had," says Winfrey. She listened to Skloot's interview tapes, met with the Lacks family and scrutinized the book. "She put a lot of pressure on herself to bring Deborah's story to life," says Byrne, adding that on the set, Winfrey was reserved. "She wasn't the bubbly Oprah personality, the TV journalist we've all grown up with."

But Wolfe "is a genius at nuance and interpreting emotional behavior," says Winfrey. Under his guidance, she found ways to capture Deborah's essence without mimicking her. Skloot, who served as co-producer of the film and was often on the set during filming, verifies the accuracy of Winfrey's portrayal. "She became Deborah," she says. "I felt like she was in the room with me."

In the movie, Deborah finds peace as she learns the history of HeLa. At a Johns Hopkins laboratory in the same building where her mother's cells were first taken, Deborah stands in the green light of a magnified image of HeLa cells. Basking in that glow, it is as if she is being infused with the warmth of the mother she never knew. "Now she is complete," says Wolfe.

Related: Genetic signatures may help stop aggressive cancers in their tracks

After Immortal was published, the Lacks family, many of whom were children when Deborah died, became deeply involved in educating students and the public about her legacy and advocating for patient consent before tissue removal. Much of that work has been done through the Henrietta Lacks Foundation, which Skloot established in 2010. Two family members serve on a National Institutes of Health group responsible for supervising how data from Henrietta's genome is used. "They are doing exactly what Deborah hoped they would do," says Skloot. Although two family members have been outspoken in their objections to how their family has been portrayed (though they admit they have not read the book or seen the movie), the vast majority have been supportive of the foundation's work.

But many people who believe in informed consent—that patients should be asked before their cells are used in research—still feel violated by the medical establishment. A proposed change to the Federal Policy for Protection of Human Subjects to require such permission was shelved in the last weeks of the Obama administration, with news coverage of that swamped by the presidential inauguration. Skloot hopes the movie will stir the debate again. "Everybody wants the research to happen, but people just want to know." And science is still wrangling with racial discrimination, from the history of experimentation to current disparities in health care.

As Winfrey sees it, the story told in Immortal is part of the national conversation required for addressing this distressing rift. "Every time we get a chance to show black people and the humanity of ourselves, and the commonality of the human experience," she says, "we crack part of the code of racism."