Investigative reporter Gerard Ryle has made a career out of exposing corruption on a global scale. He's won multiple awards, written an acclaimed book and exposed the financial wrongdoings of some of the world's most powerful people. But, while highly respected in journalistic circles, he was far from being a household name. Now, in the wake of the Panama Papers exposé , he has propelled himself and the small, charitable organisation he runs, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, firmly into the media spotlight.

Before becoming the first non-American director of the ICIJ, which is based in Washington, Ryle spent 26 years working as an investigative reporter and editor in Australia and Ireland. He uncovered some of the biggest stories in Australian journalism, including the investigation into fraudster Tim Johnston, who duped the Australian, British and Russian governments over a fuel pill which he claimed would revolutionize the way energy was used worldwide. But even that pales in comparison with his latest project—the Panama Papers leak.

Ryle coordinated with more than 100 media organizations to analyze the 11.5 million files that exposed a global system of tax evasion. The documents implicate everyone from world leaders such as the Russian President Vladimir Putin, the Syrian President Bashir-Al Assad, relatives of China's President President Xi Jinping and the Icelandic Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunlagsson, who resigned earlier this week. The offshore investments of the father of the British Prime Minister, David Cameron, also were revealed—although there is no suggestion that Cameron or his father broke the law. Celebrities such as Simon Cowell, Jackie Chan and Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York, also were named in this unprecedented leak which covers a period spanning from the 1970s to the spring of 2016.

Now, the story is out, the offshore trading industry is under scrutiny, and the rich and powerful around the globe are squirming, but the question remains—how did this small organization pull this off? I caught up with Ryle to get some answers.

I guess you've had a busy few days since the story broke on Sunday?

It's been non-stop here, the phones just keep ringing. I suppose I'll miss it when it ends.

How did you first come across this story?

The documents were first obtained by a journalist called Bastian Obermayer, 38, a reporter for the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung. We had worked together in the past on other projects, such as last year's Swiss Leaks investigation [which exposed the inner working of HSBC's Swiss private banking arm]. In 2014 I learned, through Bastian, that the German government had purchased data about Mossack Fonseca [the Panamanian law firm exposed in the recent leak] from a whistleblower. That data was then offered to other tax offices around the world including those in the U.K. and Iceland.

Through Bastian's contacts we got hold of that data. It was interesting but not super interesting. That leak is unrelated to the data we eventually got but it is part of the history of how this happened. The German government raided the Commerzbank in Frankfurt in February 2015, as a result of the data they had purchased, and Süddeutsche Zeitung ran a story on it. I had a disagreement with Bastian and his colleague Frederick Obermaier, 32, because I didn't want them to reveal that we had extra information about Mossack Fonseca [in the data]. They said they had to do so. They were right, and I was wrong. They published and then someone contacted them offering more data on Mossack Fonseca. It went from there.

When did you first see the documents?

Initially, we had about one million documents, which we thought was a lot of material. Bastion received them first, through his contact. When he told me what he had I booked a flight straight to see him in Munich. The three of us then spent about four days looking through the documents.

Did you immediately realize how important a story this had the potential to be?

Yes, we all agreed this was big. Among the first names we saw were those with links to Robert Mugabe and Muammar el- Qaddafi. We saw enough names from enough different nations to know that we would be able to get an international collaboration [of journalists] together. We arranged a meeting with the editors in chief of Süddeutsche Zeitung—we had to negotiate to stop them publishing the story straight away. They agreed the ICIJ would be in charge of putting together the collaboration. Then I flew to London and met with James Oliver, a producer on the BBC's Panorama, and David Lea, the former investigations editor of the Guardian. I wanted to know if both the BBC and the Guardian would be in? They said yes, absolutely.

How did you persuade the editors at Süddeutsche Zeitung to go against their journalistic instinct and not publish the moment they saw the documents?

It took a long time. They were being polite but I think their first intention was to publish the story quickly. But, they could see that that we knew what we were doing. Frederick and Bastion were onboard my plan—they knew it was going to take months to go through the documents.

How did you start going through such a vast amount of data?

The documents arrived in parcels. We would have indexed several million and then another million would arrive, and so on. We counted 11.5 million files that we had to index. It included every email sent by the firm over the past 40 years, every passport of every client, it was a motherlode really.

When did you decide you were ready to let other journalists in on the secret?

We hosted a meeting in Washington in June 2015 for around 40 to 50 journalists from around the world, who all travelled to the U.S. at their own expense. We rented a room at the National Press Club, where we unveiled the project and the tools we had built for it, which included a virtual newsroom and an effective search system. You can't just parcel up the documents for the U.K. and give them to the British reporters, you need to give all the reporters access to all the documents at all times. That was the only way the collaboration could work.

How did you decide who to invite to that first meeting?

It was done on trust. We invited people who had worked with us before and who we knew wouldn't waste our time. It wasn't as hard as you might think! We tend to work with reporters, rather than the bosses. Once you get the reporter excited about the story, then they will advocate for it with their bosses.

Did you manage to get all the collaborators together at any point?

We had another bigger meeting in Munich in September, with over 100 reporters. Some editors were there too including the Guardian's Kathryn Viner who flew over with her deputy Paul Johnson. That meeting lasted two days and was hosted by Süddeutsche— who allowed us to takeover some rooms at their offices in Munich. We didn't pay for anything as we are a not-for-profit organization, run on a shoestring.

How did you get everyone to agree to keep this huge secret?

We made everyone sign an agreement stating that they weren't allowed to tell anyone what they were working on. The only thing we insisted on is that the ICIJ decided when publication day would be.

Why did you chose to publish now?

We were looking at a lot of different dates. The TV crews had their needs, every country had its own considerations. The Germans wanted to publish on Saturday as that is their big day for news, in the U.S. it's Sunday and in the U.K. it's normally Monday. We had planned to go in March then quite late on the Germans realized that Chancellor Merkel was under a lot of pressure, and that the regional elections they had thought would be minor might turn out to be very significant, so then we had to convince everyone to wait for another couple of weeks.

What was your first big discovery among the Panama Papers data?

The first one was Iceland. We knew about it pretty early on but didn't know if was significant—if the prime minister had declared his interest in the offshore company, Wintris [that owned bonds in Iceland's banks. So, when Iceland's financial sector collapsed in 2008, Wintris became a creditor to those banks—an enormous conflict of interest]. The material on Iceland jumped out at us, we knew it involved the collapse of the banks, and that some of those named were in jail. We needed an Icelandic journalist we could trust and our Swedish partners recommended Johannes Kr. Kristjansson—a freelance reporter, who was quite famous in Iceland.

How hard was it for him to keep secret the fact he was working on a story which could bring down the prime minister?

It was a huge risk for Johannes. He put everything into it. He gave up all his other work for nine months to do the story and lived off his wife. I went over to Iceland to visit him because I realized he must be the loneliest person in the world. We spent a lot of time discussing strategy and how best to manage the confrontation. My policy is always to do whatever it is you would normally do—forget fetishizing another country's ethical rules. In the end we involved the Swedish television channel, SVT, in the confrontation interview with the Icelandic prime minister which went viral all round world. It was a great moment.

When did the documents concerning David Cameron's father's offshore investment fund come to light?

We knew about that early on too. I was keen to get Cameron into the story to head off criticism from the Kremlin that we were focusing on Russia. What had happened was that we put the questions into the Kremlin and the associates of Putin a week in advance of publication and instead of answering them they held a press conference denouncing us and saying it was all a plot. I think Putin thought it was all about him, so we thought we're going to wait and show it's not just about him, it's about everyone.

What was your favorite moment in this epic investigation?

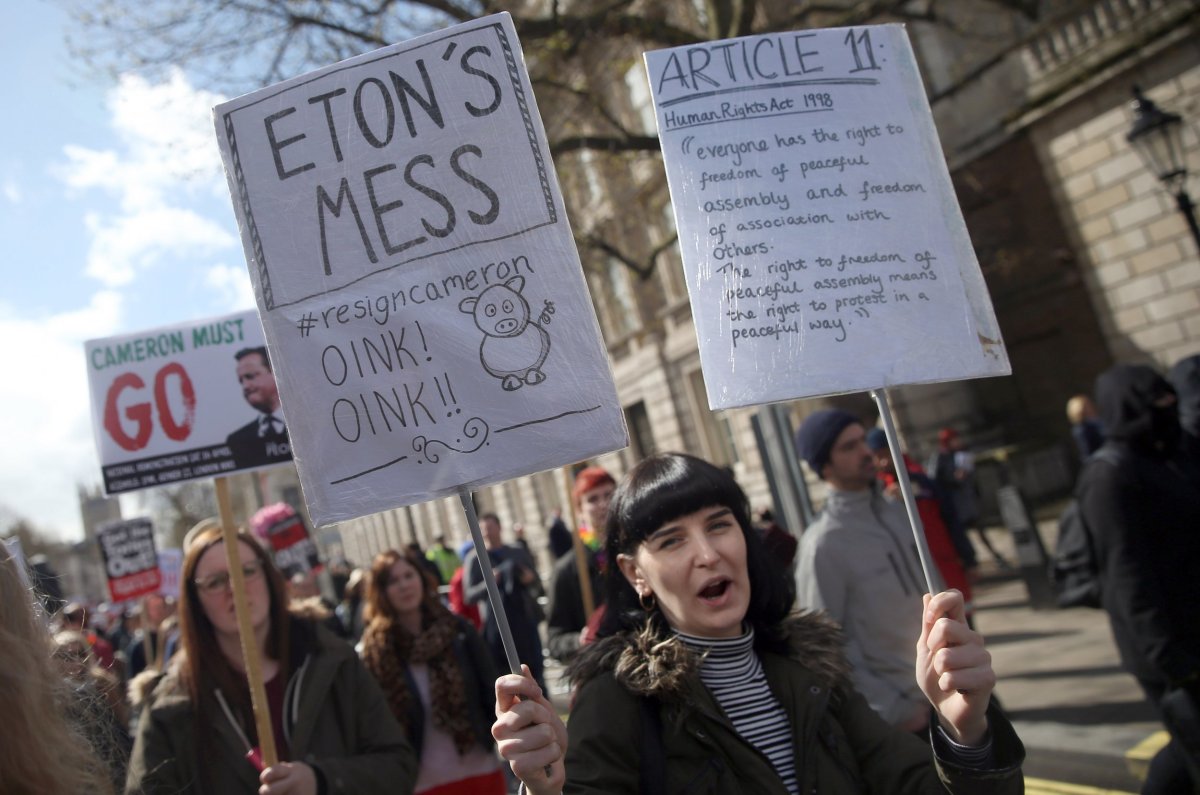

Towards the end, Johannes started saying "Wintris is coming" borrowing from Game of Thrones and referencing the name of the company linked to the Icelandic prime minister. Then after we published he was saying "Wintris has arrived." Also, coming into the office the day after publication, stressed and tired after non stop interviews to find that one of my staff had emailed me a photo of the protest outside the parliament in Iceland. The image filled my entire screen—for me that was a real "holy shit" moment.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.