Updated | The U.S. at the end of 2016 is one of the safest countries in the world. If we didn't have loose gun laws and a health care system that is inaccessible to many, it would probably rank right up there with the rest of the Western world, due to its wealth, education and its citizens' longevity. But most Americans don't believe that: They exist in a dread zone between high anxiety and mortal terror.

Watch: First trailer for 'Patriots Day,' about Boston Marathon bombing

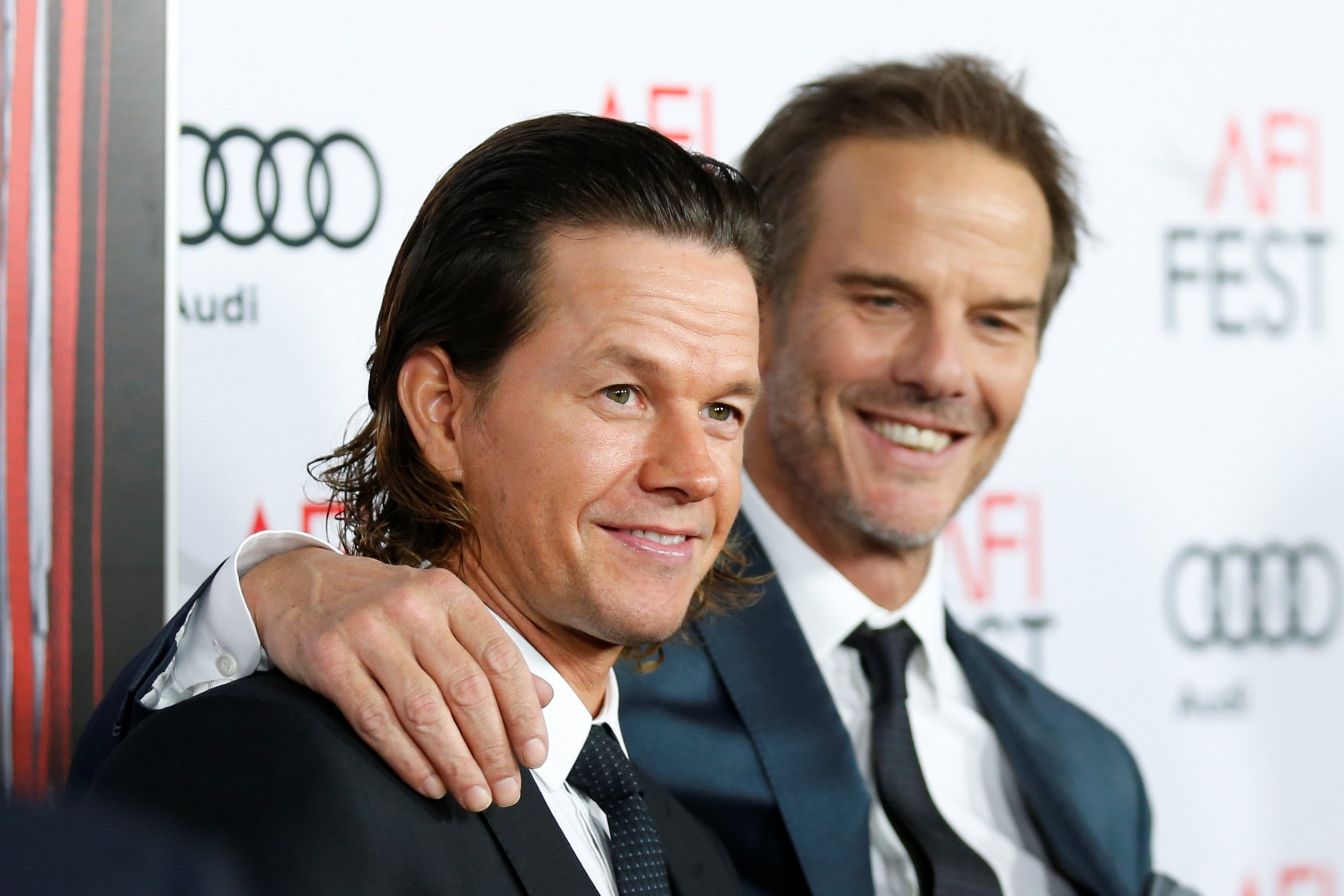

Patriots Day, the new Mark Wahlberg-Peter Berg movie about the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, will do its part in keeping that fear stoked.

The opening scene treads some time-honored movie ground. You've seen these Boston cops before: big-hearted, tough white guys who punch each other in their shoulders and call each other "chowda-head." Sometimes they get demoted by the suits upstairs just for following their good instincts. They're charged with keeping order in a great, multi-cultural, multi-colored city, a city where Hispanics, Asians, blacks, Jews, Muslims and whites form a miniature America—a mongrel America that Islamists hate.

This is the third time Wahlberg and Berg have teamed up to spin action-packed dramatic gold from real-life dross. Their other movies are about the BP oil well disaster (Deep Horizon) and a Navy Seal team's disastrous attempt to kill a Taliban leader in Afghanistan (Lone Survivor).

Critics have generally liked these flicks, and so have audiences. They hew to a post-9/11 filmmaking formula: turning actual American tragedies into (hopefully blockbuster) hero movies. Here's how it works: Producers scour the country for the rights to famous incidents of America or Americans under attack; writers identify a hero or three, throw in some jihadis if available, bring on half a minute of female love interest (the heroes are rarely female and the men are rarely gay); aaaand—action!

The test of success for these ripped-from-the-news films is whether the audience, knowing the ending, still can't look away from the screen. Patriots Day passes that. It's tense, engaging and moving, although the screening I attended didn't resemble the one described in The New York Times, where the audience gasped and sobbed.

The movie sticks pretty close to the facts, with Wahlberg playing a traumatized Boston everyman cop who happens to be at the Boston Marathon finish line when the bombs go off and in Watertown when the perp is apprehended—and pretty much everywhere in between. A few special effects will rock the multiplexes, like when small homemade bombs send police cars in Watertown flying in the air and bursting into fireballs.

But as visually and emotionally riveting as the movie is, it's politically difficult to watch. Since 9/11, Hollywood—and certain other media—have portrayed American victims as heroes. That's OK, but in doing so these productions perpetuate American exceptionalism even though jihadism is a global scourge, killing exponentially more people of other nationalities than Americans.

I saw Patriots Day on a winter afternoon when Russian and Syrian jets were decimating the last bits of a historic, ancient Syrian city caught in the war between American-backed rebels and the regime of Bashar al-Assad. There was something unseemly about watching a film in which an American city gets locked down against the threat of two young men even while in real life a city was being pulverized into dust. If there ever was an #aleppostrong, nobody is left to tweet about it; or, if they are, they've lost everything that connected them to the internet. That's also true for hundreds of millions of people around the world, where violence really is a fact of daily life.

Boston was so well defended that the perpetrators were identified within hours and one killed and the other apprehended within a few days. Their carnage was horrific: Two pressure cooker nail-bombs killed three civilians, and wounded nearly 300 others. They later shot and killed a security guard. That's real, random trauma, and it is the thing that terrifies Americans from Omaha to Baton Rouge, from Bangor to Sacramento.

In another era, Patriots Day might have been called Bombers' Day. The movie does a good job portraying what's known about the Tsarnaev brothers, their relationship and their motives. A scene of the federal counter-terrorism squad interviewing black widow Katherine Russell flicks at one of the enduring mysteries of the event. The elder Tsarnaev was probably mentally ill, and he manipulated his drifty, pothead brother into committing murder with him. But besides their jihadism, very little separates the Tsarnaevs from any other men in the pantheon of America's ideology-free mass killers, whose names are bloody spatters on American history: Whitman. Huberty. Klebold. Harris. Holmes. Lanza. Roof. Sherril. Dear.

Those white men with Anglo names have killed exponentially more Americans over the years than all the homegrown jihadi terrorists combined. But with the exception of Michael Moore's Columbine, I can't think of a recent film about any of them. Is this because our existential national fear needs an alien, foreign focus? Or is it that that the victims of violence inflicted by people who say they hate our country are more easily drafted into hero narratives than those killed and maimed by non-ideological murderers who look and talk like us?

In Boston, it is historical fact that after cops pulled the bloodied Dzohar Tsarnaev out of the drydock boat, city streets rang with jubilation usually reserved for the Red Sox and Tom Brady's Patriots: "Lets go Boston! Let's go Boston!" Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick says of the bombers at the end of the movie: "They gave us a stronger sense of community."

In New York, the since-renamed Freedom Tower—that impossible sliver of geometry against the sky, rising from the ground zero hole of 2001 and visible from so many distant odd corners of the city—reminds this community everyday of our resilience. We should be proud of it, as Boston should of surviving and uniting and supporting victims. But in the business of Americans remembering terrorism, there's a fine line between honoring and fetishizing.

At a panel discussion after the screening, Berg and Wahlberg (who hails from Boston) talked about how careful they were to personally assure Bostonians that they weren't going to dishonor Boston or exploit the victims. But they don't seem to have considered the politics of their choice of subject.

I asked Berg whether the stories of the many heroic survivors and communities victimized by all the non-ideological, gun-toting mass murderers are ripe for film adaptation. He said he had done some work in Sandy Hook for television, but did not see it as compelling movie fodder. Maybe so. And yet, surely there were heroes in the Sandy Hook massacre—and in Aurora and Charleston, to name but a few—men and women who died or survived heroically, and whose communities rallied and came together behind them.

Top Hollywood directors and actors have many choices about what stories to put money and talent behind. Movies about jihadi violence against Americans on American soil reaffirm a prevailing anxiety, and thus can become box-office gold. Maybe that's all that matters. But the choice of story is also a political act. Patriots Day tries to be about heroism in a multi-cultural community. But as a choice of commercial movie subject, it encourages the terror and xenophobia shared by so many Americans who think—without any factual basis—they'd be so much safer if their country was just a few shades whiter.

This article has been updated to clarify how a security guard was killed after the Boston Marathon attack.

Read more from Newsweek.com:

- 'Rushmore' and 'The Lion King' among films added to Library of Congress Film Registry

- The shows and films coming to Netflix in January

- Friend of Boston Marathon bomber set for prison release after sentencing of time served

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Nina Burleigh is Newsweek's National Politics Correspondent. She is an award-winning journalist and the author of six books. Her last ... Read more