Honolulu lies on a great sickle-shape of bay, the crescent that connects the scoop of Pearl Harbor to the crater of Diamond Head—an emblematic sight that appears in the earliest engravings, as well as the most recent photographs of the city. This combination of beach and crater cone, backed by deep-green folded cliffs, makes for a dramatic natural setting. Yet it is not a beautiful city. It is a sprawl of tumbled bungalows, a few tall buildings, and many coastal hotels.

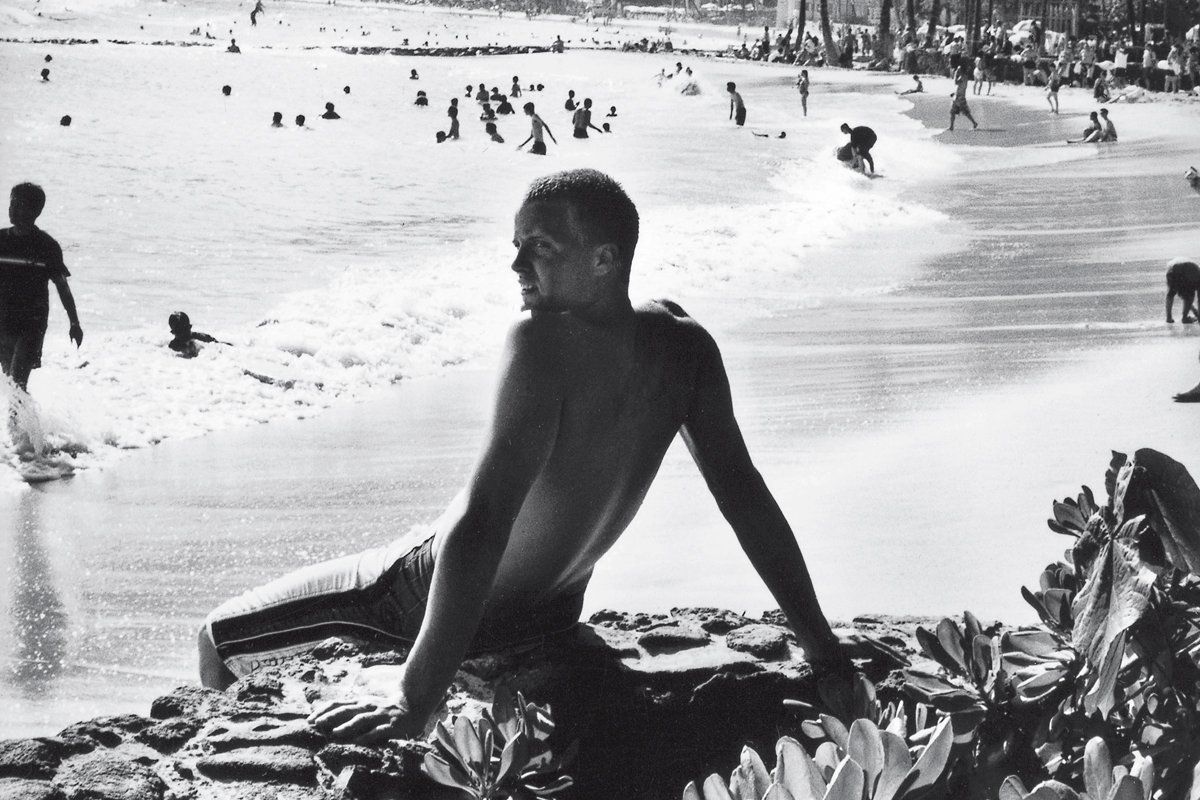

Any city planner with foresight would have taken advantage of the dramatic serenity of this seafront and fashioned a corniche, a road along the ocean, as in Alexandria and Nice and Eastbourne, to give drama and beauty to the city. But Honolulu wasn't planned—it was improvised by philistine businessmen, real-estate developers, land grabbers, opportunists, me-firsters, and schemers. Their demand for seafront property meant a building boom that blocked the view. The boom goes on. The ocean is invisible from most of Honolulu's streets. Fortunately, all beaches in Hawaii are public: you can sit on the sand or swim in front of the most expensive beachfront house or chic hotel.

The smash of sunlight on the sea brightens Honolulu, which has the best weather and cleanest air of any city in the world. Locals seldom remark on the weather unless it's raining; they love the lights; the pretty song "Honolulu City Lights" is one of the city's anthems. But on rainy days Honolulu is radically altered, and its face made plain. While New York and Paris are more beautiful in bad weather, Honolulu in the rain is a prosaic, not to say ugly place. Its few lovely buildings are its oldest, and are rather small, and hidden. Its most venerable building, Washington Place, home of the governor, is a white candy box behind a hedge—lovely, but scarcely visible. Honolulu has no municipal architecture of any beauty; its hideous traffic makes it unfriendly to pedestrians; just a few streets define its downtown.

The city is sprawling and hard to define. Look closer and you see not a city but a collection of seaside neighborhoods, backed by the folded cliffs and ancient lava flows; the creases now softened by the greenest foliage imaginable. I live in a small rural settlement some distance away, but I like Honolulu because it seems more a small town with pretensions than a real city.

Honolulu has been disrespected by most of its literary visitors. Herman Melville passed through in 1844 and mocked it for its missionary hypocrisies. W. Somerset Maugham, who saw little more than the harbor, portrayed the city as seedy. For James Jones, Honolulu was a soldier's fantasy of loose women. James Michener was fair-minded about the city in his novel Hawaii, but was resented for writing it; and when he met opposition for wanting to live in the posh neighborhood of Kahala, it was front-page news.

After I published my novel Hotel Honolulu, I was jeered at for seeming presumptuous. I tried to put the multi-layered complexity of the city into that book, the way the city is a beach for some, a place for bingeing and getting sunburned; for others a place of proud neighborhoods and small schools—you are pigeonholed in Honolulu for the high school you attended; the prom is the social highlight of the year for many. President Obama was raised in one of these neighborhoods, in an apartment house that is often described as modest, on a side street, a 15-minute walk to his high school.

Ask tourists why they like the city, and they will name a hotel or a Waikiki restaurant. These people have no idea that Honolulu is a secret city, a place of beloved noodle shops, sushi bars, grocery stores; a park where a softball game is usually in progress, or a church hall is hosting an orchid-growers' club. This city of the residents is self-contained, secure in its smugness, and dense with churches. It is truly multiracial and tolerant not because it is colorblind but because it is a society acutely sensitive to race.

People in Honolulu express themselves by eating. One of the most successful charitable efforts recently was "Eat the Street for Japan," a large gathering of lunch wagons crowding a neighborhood; thousands of people eating and, content, donating money for Japan's tsunami and earthquake relief. It seemed a peculiarly Honolulu event, a way of using the city virtues, the outdoor party, a combination of balmy weather, fresh air, good humor, voracious appetite, and generosity.

Theroux is the author, most recently, of The Tao of Travel:Enlightenments From Lives on the Road.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.