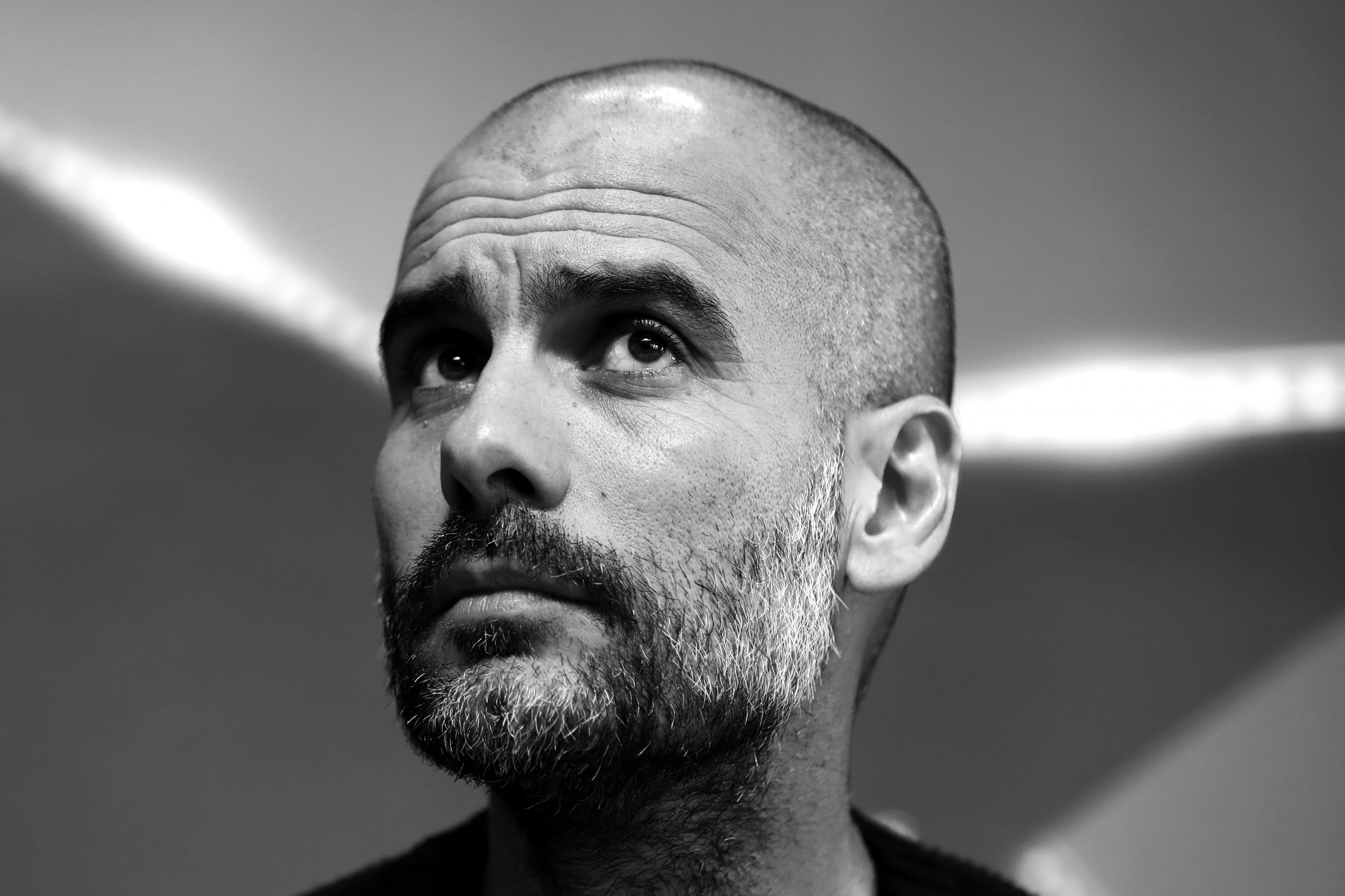

In the summer of 2016, the most celebrated manager of football's modern-day era arrived in the English Premier League to take charge of Manchester City by way of Bayern Munich.

Pep Guardiola began his coaching career at Barcelona, where he had excelled as a player, turning a team that had begun to stumble under Frank Rijkaard into one of the game's greatest ever sides, both in terms of aesthetics and results.

When Guardiola moved to Bayern in June 2013, he faced a challenge of his philosophy. Shorn of his home-grown Barcelona talent, including Xavi, Andres Iniesta, and most importantly of all, Lionel Messi, would the Spaniard stick to his distinctive style or acquiesce to the Bavarians' different demands?

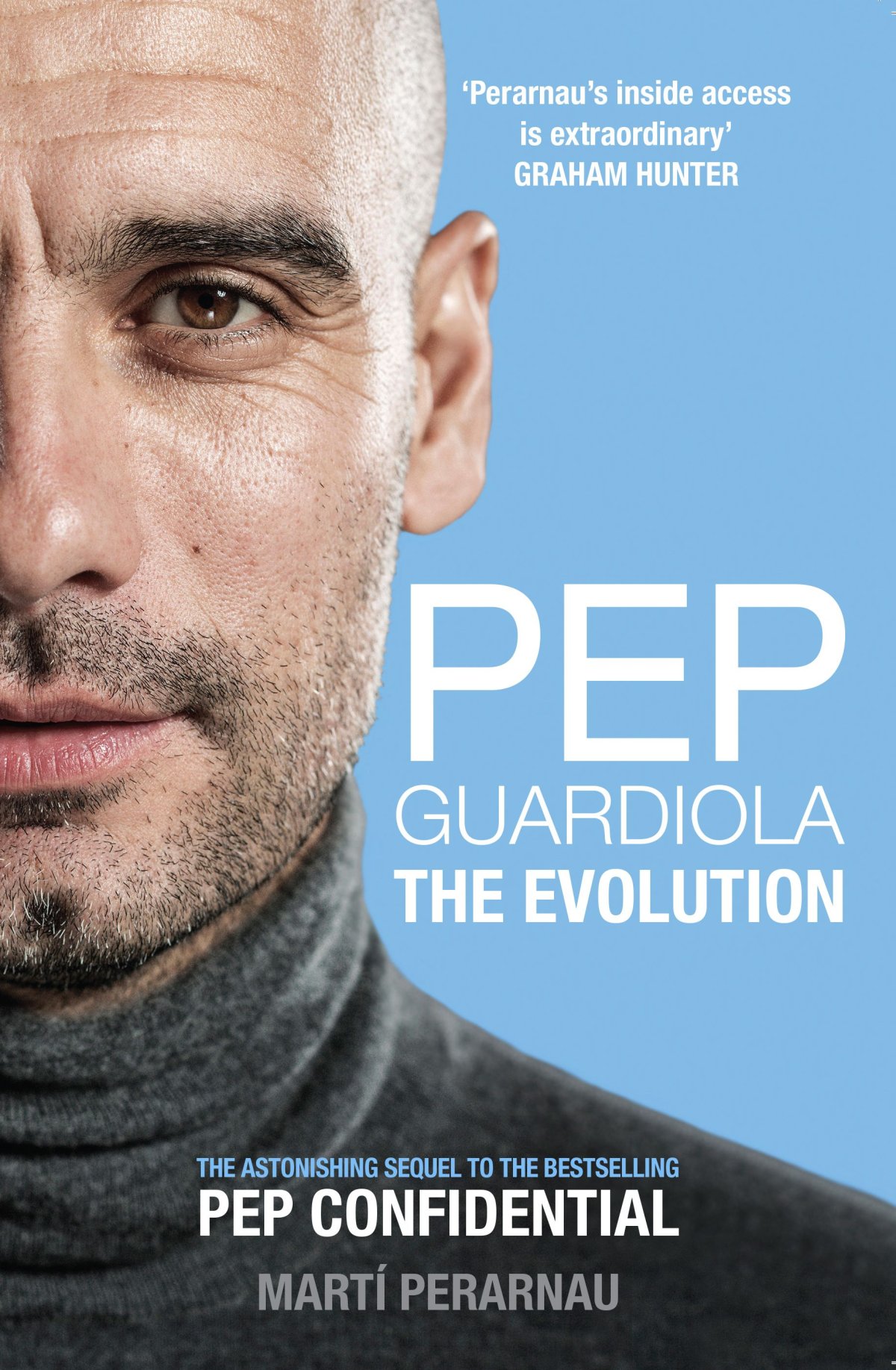

In this extract from a new biography, Pep Guardiola: The Evolution—which also takes in the start of his career at City—author Marti Perarnau explains how Guardiola received advice on updating his methods from an unlikely but brilliant source.

When he first arrived in Munich, Pep fully intended to bring Cruyff's and Barça's game to Bayern. However, almost as soon as he was established at the Bavarian club it became clear that he'd have to go another way. There were two reasons for this: he understood immediately that he lacked the right kind of players to reproduce the same playing model and the wide range of talent in the squad opened up whole new possibilities in terms of strategy and tactics.

Ferran Adria, considered the world's best chef for many years and certainly the most creative and groundbreaking of his peers, was happy to share his observations about Guardiola. His comments about the need for personal development and education were particularly insightful. 'In my view, Pep went to Bayern too soon. He would have been better taking not just one sabbatical year, but actually two or three to travel extensively and educate himself about the rest of the world.

I understand a club like Bayern is hard to turn down—there aren't many clubs with such an impressive history and track record—and he really had to grab the opportunity when it came his way. I still say however that it would have been better for him to spend some time expanding his horizons. I'll explain why. Basically Pep has never developed a scientifically tested working methodology. That's why I encouraged him to visit MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) during his year in New York. MIT is the most pioneering center of innovation in the world and I wanted him to meet Israel Ruiz, its executive vice-president, and see the work they're doing in their technology and design department, MediaLab. I really felt that it would help develop his own methodologies.

'It's one thing to be a football expert who has watched thousands of games but it's quite another to know how to apply scientific principles to your work. It's almost like your players are robots on whom you test your ideas. Or at least that would be the ideal scenario in a scientific context. When you talk to Pep he always says, "At Barça, my tactics consisted of getting the ball to Messi." You never really get a sense of how Pep judges his own performances.

We're good friends and I think I know him pretty well but I don't see him applying any kind of tried and tested scientific approach to his work. Obviously it's a tough ask, because it would involve getting away from football altogether for a couple of years. But it's the only way to get the mental space necessary to start decodifying the game and then begin to construct the right methodology. I did it. I closed my restaurant el Bulli, put some distance between myself and my work and then started to de-codify cooking.' Adria gets it spot on when he quotes Pep because the former Barça manager has often said, 'When I was at Barcelona I saw my job as making sure the team did the right things at the right time to get the ball to Messi exactly when he needed it. And then Messi would score.'

A different approach was required at Bayern. There was no Messi to work his unique brand of magic, nor a group of players who'd been trained since a young age in how to apply his philosophy on the pitch. So the coach had been obliged to construct a different circuit-

board of football at Bayern, very different to that of Barcelona—most of all because he lacked a miraculous creator and taker of goals like Messi.

Adria sees parallels with basketball. 'Phil Jackson used to say that it was what Scottie Pippen did for the Chicago Bulls that allowed Michael Jordan to be Michael Jordan—and Xavi and Iniesta were the ones at Barça who allowed Messi to be Messi.' Bayern couldn't offer Pep a Messi or a Xavi, but it was this that in the end proved the stimulus to come up with new, more imaginative ways of winning.

Adria says that Pep's deliberate decision to test his own capabilities was the catalyst for the explosion of creativity and new-found versatility we witnessed. 'Almost immediately Pep realized that Bayern couldn't be another Barca. He had no Messi, no Xavi or Iniesta and without these three key players it would be impossible to recreate the monster he'd unleashed in the Catalan capital. So he did the smart thing and decided to rely on his own instincts and resources. He was effectively testing himself.

Had his success at Barca been a flash in the pan? There was only one way to find out. And, as we know now, nothing could be further from the truth because Guardiola went on to reproduce the same basic model but with modified concepts and different interpretations at Bayern. Some concepts changed because they were inapplicable, others because there were more appropriate ways to apply them… only the absence of Messi (and Xavi and Iniesta) prevented him from replicating the full glory of his Barca years and his many triumphs at Bayern prove beyond doubt that, with or without a touch of Messi magic, his model works.'

After having spent three years observing Guardiola at Bayern, I believe that this new-found eclecticism is now a central part of his character. He has successfully fused the philosophy of a radical 'Cruyffista' (possession, passing, attack, defending high up the pitch) with the German qualities of speed and vertical play, putting the ball into spaces, crossing into the box and overloading attacks.

In reality, the true measure of a coach is not so much the quality of his convictions but rather his ability to teach and embed them even in less than ideal conditions. A good coach should be constantly revising his beliefs, amending and adapting them to achieve the perfect synergy between his own philosophy and the club he represents. A belief system should never become the straitjacket of dogma and it's clear that Guardiola now sees his philosophy as just a frame of reference within which he can move and expand.

Pep Guardiola: The Evolution by Martí Perarnau is published on 4 November by Arena Sport (£14.99, paperback). Available from all good bookshops and at www.birlinn.co.uk.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.