This year is the International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements—and today (March 6), the modern version celebrates its 150th birthday.

To find out more about the table and how new elements are added to it, Newsweek spoke to Molly Strausbaugh, assistant director at the Chemical Abstracts Service—a division of the American Chemical Society. Below is a transcript of our conversation, which has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How was the periodic table developed? What's the significance of March 6?

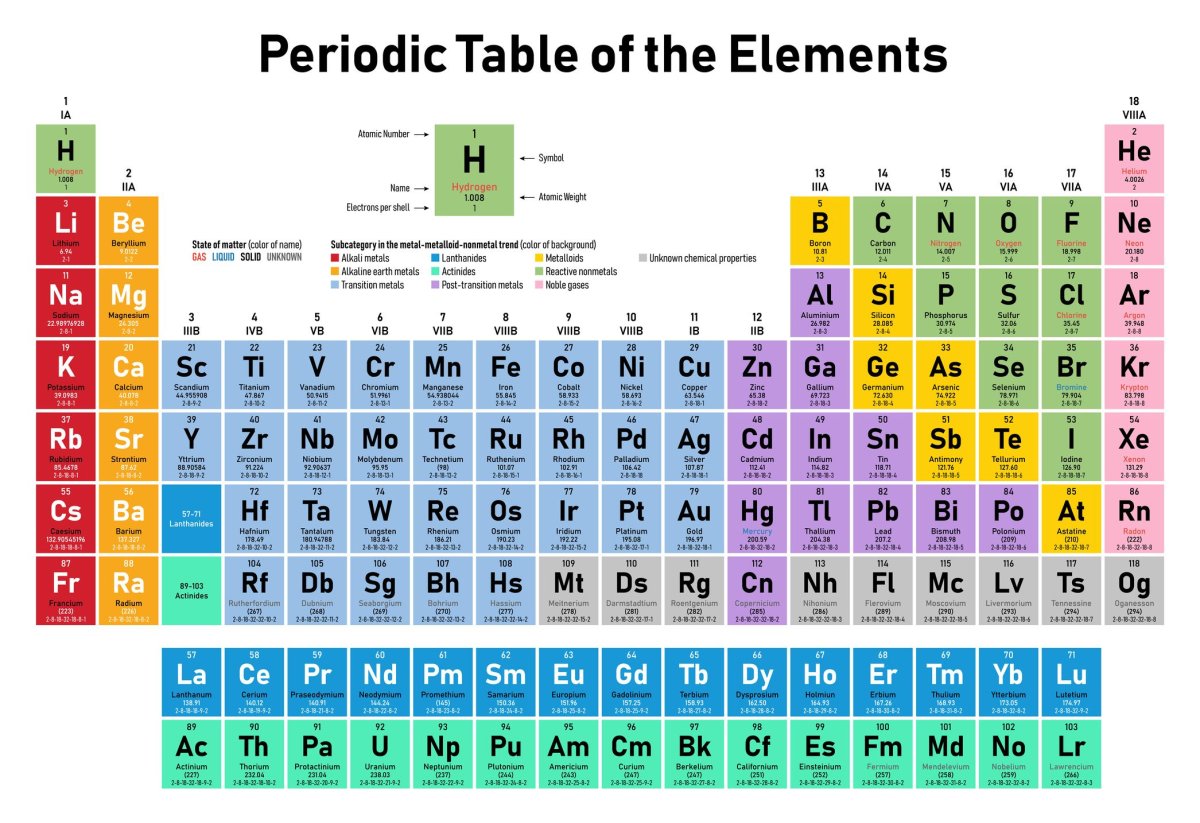

The modern periodic table was developed by [Russian chemist] Dmitri Mendeleev and March 6 is significant because that was the day in 1869 that it was presented to the Russian Chemical Society and released publicly. In developing it, what Mendeleev did was start arranging elements in order of atomic weight and then grouping them.

If you look at the construction of a periodic table, it goes down in rows and columns. I would consider the columns groups, which are arranged by chemical and physical properties. The rows, or periods, are arranged by the total number of electron shells (so same period, same number of electron shells) but pulling out the two bottom periods (rows) is about also fitting the periodic table on a page.

What elements have recently been added to the periodic table and how are new ones discovered? Can you give some examples of any particularly interesting ones?

The most recent ones have been Nihonium, Moscovium, Tennessine and Oganesson—so numbers 113, 115, 117 and 118. These are all man-made. When we talk about Nihonium—I'm going to pick on that one—the name is one of two ways to say "Japan" in Japanese. Nihonium is the first modern element that was discovered in an Asian country.

These are coming from particle accelerators. They are being produced. So essentially you have a target—something to hit—and you've got to have a particle that's hitting it. Then you're looking at what comes out; it's done very fast. These new elements are the result of chemists and physicists working together. So, there's definitely design, technology and resources that go into making elements like this.

What's the drive behind this kind of research? What are scientists trying to gain from creating new elements?

It provides a better understanding of our universe and it furthers technology. What can we do, and what can we learn?

Which was the last non-man-made element to be discovered?

From a purely natural standpoint, Francium, discovered in 1939, was the last element that was first discovered in nature. Some other elements discovered after that are naturally occurring; however, the original discovery process was man-made.

So once a new element is created in a particle accelerator, what's the process between that point and it actually appearing on the periodic table?

So, you can't just say I've got something and there it is. There is a definitely process. When someone says, 'I've found something,' they would report their discovery to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), as well as the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics. They have a joint working group.

So, you would report your discovery to this working group, then it would be established and verified. Subsequently, those who have been part of the discovery process are invited to propose a name and a symbol to IUPAC's Inorganic Chemistry Division. Typically, we'll see elements named after people, places, mythology, maybe a mineral or similar substance, or a property of the element. Helium, for example, comes from Helios [a god in Greek mythology].

Are we likely to see more man-made elements created in the next few years?

I would say that the search continues, we're seeing a lot of different theories that are published about that—what approaches are there, what technologies are there, how far can we go. So, I'm not going to make a guess on that but there's definitely a lot of research coming out through peer-reviewed articles.

Is there a theoretical limit to the number of elements that we can identify?

I think this is unknown territory, there are plenty of theories that are out there. Essentially, I don't think that we know.

What is the value of the periodic table?

The periodic table is a fundamental part of understanding chemistry. Elements define our universe: they are the components and foundation of the substances that we interact with every day.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.