The drag queen, pitched precariously on top of the prison, tottered improbably at the building's edge, in a little black dress, high heels and mountaineering gear. The occasion, this past July, was Philadelphia's popular Bastille Day celebration, a block party for the French Revolution with musical theater, political satire—and this splash of danger.

John Jarboe, high atop the 189-year-old Eastern State Penitentiary, long closed and turned into a tourist attraction, was playing French chanteuse Édith Piaf. Then he did what—judging by the gasps—some 1,000 people clearly thought he wouldn't do. He climbed over the edge and began to repel down. The crowd held its collective breath as, a few hops and a couple of furtive shuffles into his descent, Jarboe stopped beside a covered banner and tore away a sheet to reveal a single word: "RÉSISTEZ."

Wilder shouts broke out, and for a moment, as the crowd's fever seemed to build on itself, it felt as if insurrection really was in the air. This was Philadelphia, after all, home of the American Revolution and a city proudly anti-Trump. Even better, at the climax of his show, Jarboe introduced "a real, living revolutionary": the city's new district attorney, Larry Krasner, who is achieving a kind of celebrity rare for a city prosecutor. Since taking office in January, he's been a guest on network news shows, and even Comedy Central, as well as an adviser to 2020 presidential candidates—all because he's blowing up what prosecutors do: promising more lenient prison sentences for nonviolent offenders, legalizing pot possession and prostitution, and eliminating cash bail so the poor aren't stuck in jail before trial.

At the Bastille Day show, Krasner gamely followed a script that echoed his campaign speeches. "You keep calling this a mob," he said to "Piaf." "But it looks like a movement to me."

Taking the mic from Piaf, he fired questions at the crowd: "Do you want people with mental illnesses to be treated for those illnesses rather than incarcerated?" he asked. "People with drug addictions…nonviolent offenders?"

At each question, the crowd hollered back—stiffly at first, then strenuously, catching the moment: "Yes!!!"

In a final flourish, Krasner waved his hand and liberated "Bastille" prisoners, who poured from the penitentiary. It was a stirring performance, perfectly symbolic of what Krasner has framed as "a movement"—one that will remake the criminal justice system.

At one point, the Piaf character asked Krasner, "Why, Larry? Why do I find you so attractive?"

"That's normal," replied the DA, sleek in a black suit and tie. "When you do radical things, you just look really hot."

Even in liberal Philly, the existence of Krasner's candidacy set off a political earthquake. A career defense attorney, he never prosecuted a case in his life. And within the world of Philadelphia's celebrity defense bar, he was never among the first rank. He wasn't a go-to guy for the city's mob, nor did he spend decades pulling down headlines, trying the city's most sensational homicide cases.

Instead, when protesters from Occupy Philadelphia and Black Lives Matter got arrested, he defended them. And he sued the police department at least 75 times for civil rights violations. He'd enjoyed a career, he liked to joke, that rendered him completely "unelectable."

"I get it," says Chuck Peruto Jr., a longtime city defense attorney. "The fear people had around him. Everyone wanted to know: Whose side will he be on? The defense or the prosecution?"

Whose side are they on? is the foundational question facing all reform DAs around the country, from liberal enclaves like Chicago to more conservative bastions like Columbus, Mississippi, where candidates have run and won on platforms like Krasner's. Now that they're in office, they need to define themselves in a way voters find comfortable, or someone else will define them.

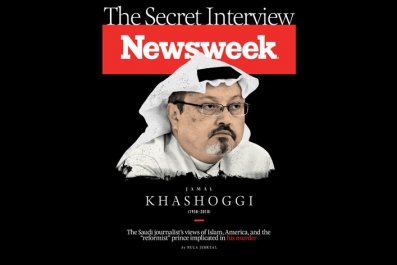

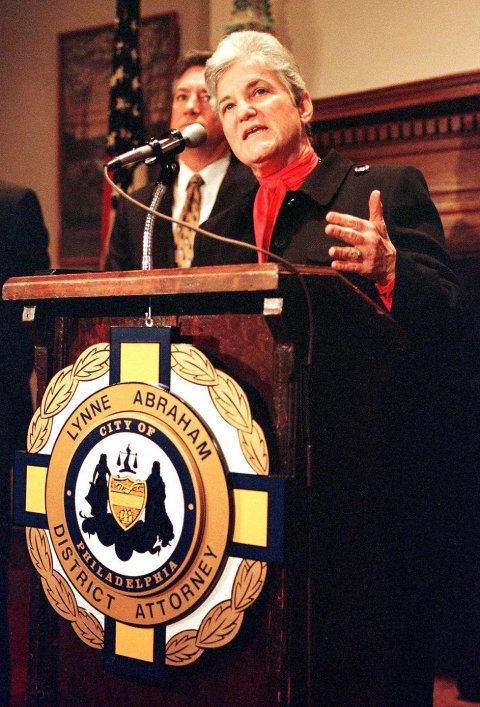

And that dynamic in itself is something new. Because for many decades we've known exactly what to expect from sitting prosecutors. In Philly, that is best exemplified by former DA Lynne Abraham, a diminutive, sweet-faced grandmother who ran under the banner "one tough cookie" and sought the death penalty with such regularity The New York Times dubbed her "America's deadliest DA."

Nationally, the phenomenon of aggressive prosecution extended from seeking the harshest possible sentences, all the time, to what legal scholars and enterprising reporters dubbed a "win at all costs" mentality. While arguing that they must "speak for the victim," a phrase that appeared, on its face, unassailable, some prosecutors broke the law, engaging in outright misconduct, such as withholding evidence that might point to the defendant's innocence.

The National Registry of Exonerations, which tracks wrongful convictions, has recorded 2,287 exonerations in America since 1989, of which 50 percent include "official misconduct" by police or prosecutors who were responsible for the false imprisonment. Philadelphia has had 23 exonerations. Krasner is determined to see if that number is low.

In this environment, the idea that a career defense attorney, vowing to favor the scalpel over the sledgehammer, might run and win seemed impossible. But social activism, particularly the recent efforts of groups like Black Lives Matter, has helped reshape the landscape, driving the conversation about justice reform to center stage. As a result, Krasner ran at a choice political moment for an insurgent candidate. And since his win, he has become the poster boy for what is becoming, yes, a movement.

I meet Krasner in his office, a long and book-lined aerie on the 18th floor of a Center City high-rise, a few days after his Bastille Day performance. He cuts the figure of a professorial dream date: Fit and trim at about 5 feet 10 inches and 170 pounds, he looks ready to run marathons. His personality, however, is a bracing mix of the theatrical skill you would expect from a career-long trial attorney and the plain talk of a farmer from the Midwest, where he grew up.

I found him still willing to marvel over his campaign. "I get that my candidacy was, in a certain respect, 'funny,'" he says. "I actually laughed about it myself."

But he never considered himself a long shot. His wife, Lisa Rau, a city judge known in Philly legal circles for being skeptical of police testimony, had run an outsider campaign back in 2001, winning a Democratic primary race. "I figured my chances were about 40 percent," Krasner says.

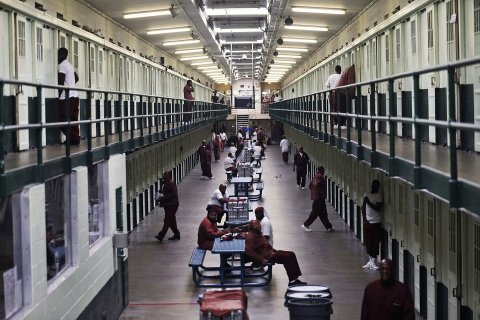

He was feeling momentum. The national prison population has boomed, since 1970, from around 300,000 to more than 2 million—a population larger than 15 U.S. states. We were locking higher percentages of our own people behind bars than even authoritarian governments in China or Russia.

And the statistics reveal an alarming racial bias: Though African-Americans and Hispanics are about 32 percent of the U.S. population, they made up 56 percent of the prison population in 2015. Furthermore, according to a 2016 report by the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan nonprofit, some 39 percent of prisoners should be free, either because they've been in prison so long they have aged out of the criminal demographic or they're nonviolent offenders.

Krasner recognized Philadelphia as Exhibit A: In 2015, it had the highest incarceration rate of the country's 10 largest cities, spending roughly $300 million a year on its prisons. The overcrowding, Krasner reasoned, sparks violence behind walls, where most of the inmates are awaiting trial, many stuck because they are too poor to pay bail. "The costs," he says, "are crippling and unnecessary." Rehabilitation services are a fraction of incarcerating someone, and that holds true, realistically, no matter how many times the person relapses and returns for more treatment. "So why," Krasner says, "when these people are nonviolent and statistically unlikely to ever be dangerous—why as a society would we not do that?"

At the same time, activists pushing for legislative fixes had come to realize that the most direct solution to reducing sentences is the DA's office. Prosecutors wield remarkable power, deciding whom to charge, with what crimes and how long a sentence to seek. They also decide if a plea deal should be offered, which is perhaps their greatest power. In the system as it exists, defendants are so intimidated by the potential for a stiff sentence that 90 percent of them plead guilty, for a reduced sentence, rather than go to trial.

Krasner considers the system hopelessly broken, and so he thought only an outsider could be trusted to fix it. When he looked at the prospective field in Philadelphia, he saw only "the usual suspects"—old attorneys who'd prosecuted cases before and didn't augur the "radical change" he felt was necessary. So, in February 2017, just three months before the primary, he announced his candidacy and discovered his past was a benefit.

Because he couldn't run from the charge that he had never prosecuted a case, he embraced it. "You're right," he'd say. "I haven't contributed to this out-of-control justice system. I fought it." After a few weeks of pitching his platform, his campaign adviser, Brandon Evans, pulled him aside and told him, "It's working." Little old ladies would listen to Krasner's response and open their purses. "They fished out little notepads and index cards," says Evans, "and wrote down his name."

Along the way, he also received attention from billionaire George Soros, who has backed reform DAs across the country: The Republican Party's No. 1 enemy funded nearly $ million to promote Krasner's candidacy. He crushed the competition.

Clearly, money matters. More than a dozen Soros-backed DAs are now in office. But the Soros touch isn't that of Midas. Three candidates he backed last year in California lost. The revolution might be funded by a liberal billionaire, but the ideas and their resonance with the public reflect a chemistry that doesn't rely on cash. And so, when Krasner took office, he didn't do it sheepishly, like someone who'd had his new title purchased for him. He took it on like a man with a mandate.

Of all the reform candidates to take office, Krasner is perhaps the most unlikely—and important. He was born in St. Louis to an extended family of grandparents and cousins who labored as farmers and mechanics. His nuclear family had intellectual heft. His father, William, the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, wrote mystery novels with titles like Resort to Murder, as well as textbooks, as a ghostwriter, in various academic disciplines. His mom, Juanita, was an evangelical protestant so open-minded in her faith that she urged young Larry to learn about his half-Jewish roots, even though his secular father "couldn't care less."

Krasner came of age in the 1970s, and the news was must-see, on TV or in newspapers, and issues like civil rights and Watergate were raised at the dinner table. He decided on law school and got his degree at Stanford in 1987. His first big job was in the office of the Philadelphia public defender. He then entered private practice after three years, with the deeply held belief that the Constitution and each individual's inalienable rights must be protected.

Where other attorneys brag about big cases in which they helped a local rapper or reputed mob boss go free, Krasner points to work he did, with a gaggle of civil rights attorneys, to identify a city narcotics squad that likened themselves to the dirty cops in the movie Training Day. That notorious crew allegedly planted drugs, falsified warrants and beat suspects for at least six years. Krasner helped free hundreds of people they'd imprisoned, and those cops aren't working in narcotics anymore.

He can also point to dozens, if not hundreds, of protesters he helped beat bogus charges. "These were people who weren't criminals at all," he says, "but their lives had been derailed because they had exercised their constitutional right to free speech."

"That's the thing about Larry," says fellow defense attorney Guy Sciolla. "He's a true believer, and a lot of people might talk about it, but his career shows you he always, always meant it."

Less than a week into his tenure as district attorney, Krasner had 31 of his inherited subordinates called in to work on January 5; they schlepped through the aftermath of a snowstorm to face his new reality.

In what can be described only as a purge, Krasner's handpicked new managers asked for the resignations of the line prosecutors and supervisors whom he viewed as obstructionist. He also had security accompany them out the door to make sure they emerged with nothing more than their personal effects.

If Krasner wanted to send a message, he couldn't have done any better. A little over a month later, he issued a memo, setting forth policy changes. Certain charges, the memo declared, must be declined: pot possession, regardless of weight, and prostitution, for anyone with two or fewer prior sex-work convictions. Those with three prior prostitution convictions would be diverted to Project Dawn Court, an alternative sanction, where defendants could seek social and health services. And shoplifting was to be treated as a mere summary offense, unless the items exceeded $500 in value.

Plea offers, for cases excluding violent crime, sexual assault and felonies with a gun, were to have the lightest sentence possible under state guidelines. But it was another item that garnered the most controversy: Prosecutors would be expected to conduct, for sentencing, an assessment of how much the defendant's incarceration would cost and why it would be money well spent.

The last bit struck justice system professionals as part genius, part gaga. On the one hand, Krasner was connecting prosecutorial discretion to practical concerns about costs and benefits and the economic inefficiency of mass incarceration. On the other, he was asking prosecutors to undertake the kind of analysis best left to their more experienced supervisors, which would offend judges who presumably understood the costs.

Krasner's treatise has since been likened to Martin Luther's "95 Theses," the basis of the Protestant Reformation, which he reputedly nailed to a church door. And while it contained policies for his staff, it was also an open letter. "That was intentional," says Krasner. "We wrote it to be understood by people who are not lawyers, free of legal jargon, because we knew it would be leaked. But we had no idea, none, that it would bring us so much attention nationally."

The memo, which went viral online, put Krasner at the forefront of the reform movement. In the past six months, he has been more visible than any city DA in memory. He has appeared on Vice News and Full Frontal With Samantha Bee, and in the weeks I was with him, he was followed by two documentary film crews. He has been covered in The New Yorker, The Washington Post and The New York Times.

Much of the coverage bears a valedictory air. The experience of these new prosecutors is portrayed as if the fighting really has ended, and this experiment in justice reform can proceed as we imagine experiments do—unimpeded, the "scientists" involved able to carry on in peace. But in truth, this reform movement has major hurdles ahead and powerful opponents. In Philly, Krasner's critics point to those firings after he took office. And they did look cruel: old soldiers escorted beyond the castle walls by the new king.

But what people didn't know is that Krasner had conducted a listening tour before taking office. He visited with reformer DAs who'd preceded him, like Kim Foxx in Cook County, Illinois, and Kim Ogg in Harris County, Texas.

Ogg, for one, told Krasner to be careful. Like him, she had determined who would never get with a reformist program, but unlike him, she gave them two weeks' notice. In the interim, as her departing prosecutors whiled away their remaining days, events occurred, which she didn't discover until they were gone: Hard drives got wiped, and thousands of emails were deleted.

She also received calls, from victims and witnesses, telling her they'd been phoned by people identifying themselves as prosecutors, who said things like "I'm leaving because the new DA doesn't care about you."

"I'll never know what was destroyed or deleted," Ogg says, "so we'll never know what kind of damage was done."

Krasner's mass ouster was purely defensive. "We had some awareness from working as attorneys in this city—and interacting with people [in the office]—of who was really never going to get with this program," he says. "I felt we couldn't take the risk that there might be some effort at sabotage here."

As honeymoons go, Krasner's was brief. "We are in a Krasnerian experiment of justifying, minimizing, and forgiving bad behavior," wrote Stu Bykofsky of the Philadelphia Daily News, in a column about the DA's early days in office. "If the crime rate goes down," he wrote, "Philadelphia will become a national model. If it goes up, the revolution will end with Krasner's head on the chopping block."

There was little doubt which outcome the city's powerful police union wanted. Having vociferously opposed his campaign, the Fraternal Order of Police blasted Krasner as anti-cop; not only was he declining to bring charges for bread-and-butter offenses, but he also quickly expanded a unit devoted to reviewing the integrity of past convictions. Tensions rose in September, when, for the first time in two decades, Krasner leveled first-degree murder charges against a cop for an on-duty shooting. The white city police officer had shot two separate fleeing black suspects, one fatally.

Philadelphia's judges and attorneys were also skeptical of Krasner, ever alert for incidents that might show the real guy to be the satire he engaged in at the Bastille event—freeing all the prisoners. I chased down a steady stream of tips from Krasner critics about outlandish plea deals for undocumented immigrants, rioting teens and career criminals. None of them, however, were true.

Peruto, the veteran city attorney, says there are entrenched interests and people simply used to the status quo. They expect the prosecutor to go at the defendant, hammer and tongs. Anything else is suspect. "People resist change," he says, "and Larry is big change."

As of this September, Krasner had already declined to prosecute roughly 10 times the number of pot and prostitution-related charges his predecessors did the previous year. (If even half these people did six months in city jail, the cost to taxpayers—at Krasner's estimate of about $42,000 per year—would have been more than $13 million.) And he's sped up the process of resentencing for "juvenile lifers" to comply with a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that deemed life sentences for minors unconstitutional. His office's homicide conviction rate—85 percent—is in line with that of past administrations.

But as Krasner has pursued his agenda, he has drawn the ire of another, non-establishment force: victims' families. His office, this May, filed a motion declaring a nine-year-old murder conviction an "egregious example of police and prosecutorial misconduct" and dropped the charges; the accused went free. But they didn't inform the victim's family first. They tried, his spokesman said, but failed to make contact. A reporter from The Philadelphia Inquirer, however, found the family on his first try. Meka Jackson, sister of the murder victim, Antwine Jackson, said the only thing they'd ever received from Krasner was a card indicating someone from the office wanted to talk about developments in the case. But, they reasoned, what developments could there be? The killer was convicted long ago.

Steven Bernstein, a family member in another case, wasn't informed that the death sentence given to his brother's killer was being reduced to a life prison term. And in another case, the family of murdered city police Sergeant Robert Wilson III said they weren't notified that Krasner was about to finalize a plea deal until it was too late for any meaningful discussion.

This isn't a lack of etiquette, or even coldheartedness. It is a violation of state law. Victims' relatives in Pennsylvania are supposed to be notified and consulted before decisions on plea deals are reached. They are to be given the chance to speak at events like resentencing hearings. After word of these offenses leaked, the director of the state's Office of Victim Advocate called Krasner in "complete violation" of the law. The problem is that the law is toothless, listing no punishment for prosecutors who fail to comply, even if transgressions are clear.

Krasner characterized these instances as "growing pains." He brought up his own experience, 10 years ago, of having his face slashed with a razor by one of a trio of muggers, to point out he understands what it means to be a victim. But, of course, there is some difference between a legal professional with an avowed, pre-existing philosophical stance who survives an assault and, for lack of a better word, a "civilian" who suddenly finds herself standing over her child's dead body.

His critics accuse Krasner of a "win at all costs" mentality. Carlos Vega, one of the former homicide prosecutors that Krasner asked to resign in the first wave, contends that "he doesn't want the family members there at the hearings for fear the judge might be swayed by them and reject whatever result Larry is seeking."

In Florida, reform prosecutor Aramis Ayala was forced to rescind her own ban against seeking the death penalty when the state attorney general stepped in and declared that, under the law, her office was required to consider capital punishment where appropriate. Krasner has since contorted himself into an unseemly position, breaking with his own stated position to never seek the death penalty in order to avoid a similar diminution of power.

In Louisiana, an early-release program designed to ease mass incarceration was assailed after a pair of inmates, freed under the policy, were later arrested and charged with murder. Advocates of the program point to Department of Corrections statistics, which reveal that inmates in the initiative show below-average recidivism rates. (Furthermore, one of the men arrested would have been out of jail anyway by the time of his arrest.) But a pitched battle is on now, between reformers touting positive but abstract statistics and critics wielding the emotional heft of a tragedy.

Scott Colom, a reformist DA in the unlikely location of Columbus, Mississippi, has made significant strides there. "Data takes a long time in this business," he says. "But I do know that in one year I diverted more nonviolent, first-time offenders to alternative measures, like rehabilitation, than my predecessor did in seven years."

But he also admits that he can't move as fast as he'd like. The criminal justice world started focusing on the power of the prosecutor, he says, and that was right. But in practice, the prosecutor's power isn't total. "There are other stakeholders," he says, "and part of this work is to be patient and respectful of them, to listen to their concerns and show them over time that this way of doing the job works in a way that is better for everyone."

Krasner nods at these stories. "We accept that this job brings great scrutiny," he says—as it should. And he knows that at some point the media will print a story about a criminal he agreed to give a minimum sentence, or whatever, who then went on to commit some awful crime. "That will happen," he says, "because at some point it's bound to in this line of work."

His only defense against this is everything else. "I realize there is this hunt for an anecdote so powerful that it'll suggest what we're doing here is not working," he says, "and all we can do is see if the data we accumulate will show that it is working—that fewer people are in prison but the city as a whole is no less safe."

In August, critics found an anecdote. A Center City real estate developer, Sean Schellenger, was killed by a delivery man named Michael White. What facts we know hit all of Philadelphia's buttons.

Schellenger, 37, was white. He'd been arrested in the past on burglary and battery charges and convicted on a disorderly conduct charge before embarking on a career as a developer. The man who killed him, White, 20, was black, working through a diversionary program after an arrest on pot possession and theft charges from the previous year. He'd attended college courses and was active in the slam poetry scene. One night this past summer, Schellenger went out drinking with friends; at some point, they were hollering back and forth with a man whose car blocked a narrow street. White, en route to a delivery, rolled up on a bicycle. What happened next is in dispute.

Schellenger allegedly used racial slurs. White, according to his supporters, felt threatened and drew a knife from the backpack he was carrying. Schellenger supposedly stepped toward the younger man, getting him in a bear hug, and White wound up stabbing him in the back.

Krasner, in a controversial decision, agreed with the defense to reduce the charges from first- to third-degree homicide, arguing there was no premeditated intent to kill. I interviewed a law enforcement official who saw a video of the incident and describes the homicide as a "three-second murder," meaning everything happened so fast that first-degree murder doesn't fit. But Schellenger's parents both blasted the decision. Linda Schellenger even claimed the new DA had "manipulated" her when they spoke, telling her she wouldn't need to attend a hearing because "nothing would happen." The family attended anyway, she says, and watched, blindsided, as Krasner agreed to reduce the charges. Krasner's legal decision appeared sound, or at least defensible, but he lost the victim's family along the way.

Again, the question came: Whose side are you on?

The city's reaction illustrates how our notion of what a prosecutor is supposed to do had shifted—not in these past couple of years, when reformers began showing up, but before that, when the idea of winning steep sentences and "speaking for the victim" took hold.

In fact, a prosecutor's job isn't confined to advocating on behalf of victims. The role of a prosecutor, as defined by the courts over the years, is to "seek justice." A prosecutor, if he begins to doubt his own case, is supposed to withdraw it. A prosecutor is required to look at all the evidence available and determine if the facts of a case really fit with, say, a first-degree murder charge, indicating a cold-blooded intent to kill, or a crime of passion, more justly regarded as a third-degree homicide.

Yet for decades, we've drifted—really, motored hard—away from this vision, coming to think of prosecutors as using the full weight of their power only when they apply the steepest possible charges. And now, in the Donald Trump era, there are powerful people, like Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who want to make sure we continue handing out the steepest possible sentences.

"My job," Krasner tells me, "is to get it right." In other words, to use the broad range of a prosecutor's tools to seek justice: the sword of a life sentence, the hammer of 20 years, the scalpel freeing nonviolent offenders from jail time, the balm of ordering them into a rehabilitation facility.

The problem, of course, is that we want it all—to see both appropriate punishments and grieving mothers comforted. Krasner's communications director declined to respond to the Schellenger family's criticisms, saying the office will continue to communicate with them as the case unfolds.

But it is also true that as these stories of angry loved ones grow, from Meka Jackson to Linda Schellenger, they begin to look like a pattern—evidence of a systemic problem in Krasner's office.

Erin Boyle, a line prosecutor who was asked to resign in June, remembers one of Krasner's new supervisors complaining after visiting a family. "He was saying, 'How dare they talk like that to Larry?'" Boyle says she explained, "'This is part of the job. When you're telling an upset family member something they don't want to hear, you have to listen respectfully and let them express their emotions.' But they just don't seem to get it, and I worry that maybe it isn't in them."

Whitney Tymas, the leader of Soros's PACs, says the fate of any single reform prosecutor isn't that important. "This is a movement," she says. "Nothing is going to stop it." But the moment one of these reform DAs loses a seat, the revolution in that city ends. And Krasner, fair or not, could be rendered vulnerable.

Toward the end of our time together, he tells me he doesn't care if he gets re-elected. "I'm not a politician," he says. "I have no intention of running for any other office, and I'm not even sure I'll run again for this one."

These words are, to put it mildly, somewhat shocking. Could Krasner really see all his work end, and things go back to the way they were, without feeling some remorse? "Well, you're right," he says. "I do care very much that the work we're doing here continues. I guess what I'm really saying is it doesn't have to be me that does it."