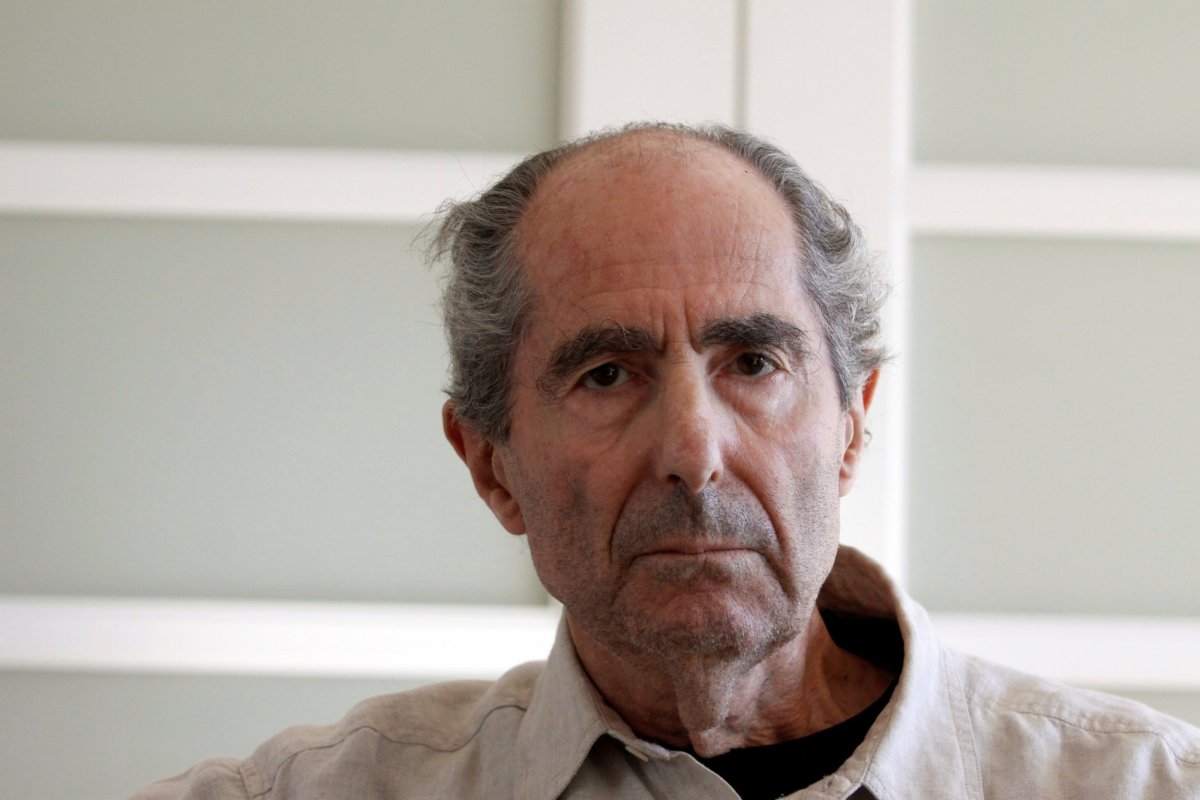

Philip Roth was a "giant of American literary fiction," "a titan of American fiction" and "a towering novelist," according to several of the many obituaries and tributes that have flooded the media since his death Tuesday night. He was a "novelist"—that's it, just a novelist—according to Wikipedia, the author's onetime nemesis.

But what about his nonfiction? Though known primarily for his novels (especially the scandalous for its time Portnoy's Complaint and the Pulitzer Prize–winning American Pastoral), the late author also was a skillful and outrageous chronicler of his own life. His memoirs and essays remain underdiscussed in his oeuvre, during his lifetime and now after.

Of course, with Roth the fundamental genre distinction—what's real, what's fake—was never quite so clear. "I write fiction," Roth once wrote, "and I'm told it's autobiography. I write autobiography and I'm told it's fiction, so since I'm so dim and they're so smart, let them decide." Confusingly, Roth wrote this line as "Philip," the quasi-fictional protagonist of his 1990 novel, Deception, who obviously shares real-life attributes with the author. (Give the audience a break for being confounded, Phil.)

Roth was well into his 50s by the time he published a book of new material marketed as nonfiction. Perhaps he had felt that his novels, with their unmistakably ruthless satirizing of Jewish-American life and libido, came close enough to life already. In 1988, he published a memoir, The Facts: A Novelist's Autobiography, chronicling his early life and career. But the title is winkingly ironic—even here, Roth indulges in sneaky narrative tricks designed to complicate the relationship between the writer and his work. (The book, for instance, contains a letter of critique purportedly from Roth's fictional alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman, to Roth.)

As anybody who obtained an English degree in the past 40 years can attest, Roth took delight in blurring the lines between reality and storytelling. There were the Zuckerman novels—including, among others, The Ghost Writer, Zuckerman Unbound and The Anatomy Lesson—each narrated by that Roth-like surrogate character. There was his series of "Roth novels"—including the eerily prescient The Plot Against America—which were told from the point of view of narrator "Philip Roth."

Other texts flirted with real-life characters: The 1971 satire Our Gang was an obvious (and heavy-handed) satire of Richard Nixon's administration, while Eve Frame, a character in 1998's I Married a Communist, was widely interpreted to be an unflattering stand-in for Roth's real-life ex-wife, actress Claire Bloom. (Bloom had, two years before, chronicled their marriage in a less-than-fairy-tale-like memoir.)

But more than 30 years into his publishing career, Roth set aside the meta-narrative bells and whistles and wrote movingly and straightforwardly about his own life and family.

The book was Patrimony, Roth's disarming 1991 memoir about the life and slow death of his father, Herman Roth. Like Joan Didion's astounding 2005 memoir, The Year of Magical Thinking, Patrimony represented a great American writer's attempts to come to grips with the confounding totality of grief. But whereas Magical Thinking was a memoir of loss—Didion's late husband, writer John Gregory Dunne, is depicted primarily as an absence, a "void"—Patrimony was a memoir about losing. Roth wrote much of the book in a state of "anxiety and bewilderment," he explained, before his father died but after he was discovered to have a large but supposedly benign tumor in his brain (which would eventually kill him).

In Patrimony, Roth employs his remarkable eye for comic detail in chronicling the absurdities of medical jargon and elderly care. There is none of the trademark lust or sexual exploits, because there is nothing sexually arousing about MRI scans or facial paralysis. But there is the characteristic tension between Roth's ornately detailed prose and sentence structures and the sordid matters being described (such as, for instance, an unflinching account of his elderly father soiling himself). And there is a certain poignancy in Roth's writing about his father's utter lack of poignancy: This is a man so averse to sentimentality that he begins disposing of his late wife's clothing 30 minutes after her burial, "driven by some instinct that might be natural to a wild beast or an aboriginal tribesman."

Like his fiction, Roth's memoir was marked by a preoccupation with self-interrogation. (Perhaps this is why Roth's critics sometimes blasted him as a self-loathing Jew.) But here he did not need to invent a psychoanalyst (as in Portnoy's Complaint) or a fictional alter ego to scrutinize the protagonist. He was the protagonist, and his father was present to do the scrutinizing, either in the corporeal world or in the subconscious. After the old man dies, Roth chooses to have him buried in a shroud instead of a suit, and then dreams that his father returns to reproach him for not choosing the suit: "You did the wrong thing."

Unlike Didion, Roth never took much interest in writing journalism. He was not trained as a reporter, and, as he wrote in 1963, in response to his fiercest Jewish critics, "to confuse a 'balanced portrayal' with a novel is finally to be led into absurdities."

That essay, "Writing About Jews," serves as a useful introduction to Roth's skill as an astute essayist and commentator. It is overwhelmingly defensive in places, but considering Roth's status as an iconic literary Jew, it is easy to forget how much discomfort and outrage there was in the Jewish media over how Roth's early work depicted Jews. Roth was blasted in editorials and letters, and even by a rabbi addressing the convention of the Rabbinical Council of America.

In his response, Roth articulated a clarifying mission statement that might apply to his lifelong interest in tales of perverts and adulterers: "The test of any literary work is not how broad is its range of representation...but the depth with which the writer reveals whatever it may be that he has chosen to represent."

Up until the final years of his life, Roth remained sporadically active in public discussions of his work. Any consideration of his nonfiction would be incomplete without mention of his hysterical 2012 New Yorker piece "An Open Letter to Wikipedia," in which he picked a feud with the online encyclopedia after its editors refused to let Roth himself correct a misstatement about his own book: "I understand your point that the author is the greatest authority on their own work," Roth's representative was told, "but we require secondary sources."

One wonders why a 79-year-old Roth—who expressed very little interest in having an internet presence—would be so preoccupied with a single line on Wikipedia, but his willingness to publicly lampoon the self-important website brought delight to his fans. (According to New Yorker editor Michael Agger, Roth faxed in the piece and chuckled when he was told about minor edits.)

Roth retired from writing in 2012—"the struggle with writing is over," proclaimed a Post-it note in his apartment—but he didn't really stop writing, because he continued to grant interviews, which seemed to occur in the form of epistolary and highly entertaining email correspondences.

Through these "interviews," an octogenarian Roth continued to be an active participant in political and literary affairs during a troubling era, and a master of descriptive prose.

Here he is in 2017, for instance, commenting on Donald Trump's presidency with scathing wit in a New Yorker piece:

I found much that was alarming about being a citizen during the tenures of Richard Nixon and George W. Bush. But, whatever I may have seen as their limitations of character or intellect, neither was anything like as humanly impoverished as Trump is: ignorant of government, of history, of science, of philosophy, of art, incapable of expressing or recognizing subtlety or nuance, destitute of all decency, and wielding a vocabulary of seventy-seven words that is better called Jerkish than English.

And as recently as January, Roth remarked upon the MeToo movement and male sexual desire in a colorful email exchange with The New York Times. ("I am, as you indicate, no stranger as a novelist to the erotic furies," Roth wrote to the Times. A hell of an understatement.)

In this interview, it became apparent that Roth was spending the final years of his life assessing his legacy, tying up loose ends and approaching his death candidly, even cheerfully.

"I'm very pleased that I'm still alive," Roth informed the paper of record. "It's something like playing a game, day in and day out, a high-stakes game that for now, even against the odds, I just keep winning. We will see how long my luck holds out."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Zach Schonfeld is a senior writer for Newsweek, where he covers culture for the print magazine. Previously, he was an ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.