Tim Page arrived in Vietnam as a 20-year-old in 1965 and spent the next five years covering the war, largely on assignment for Life and Paris Match magazines, United Press International and the Associated Press. In a personal essay for Newsweek, the photojournalist recalls his time covering the conflict with his peers and the uncensored daily photographic record that resulted.

Please be aware before scrolling that this post contains explicit images.

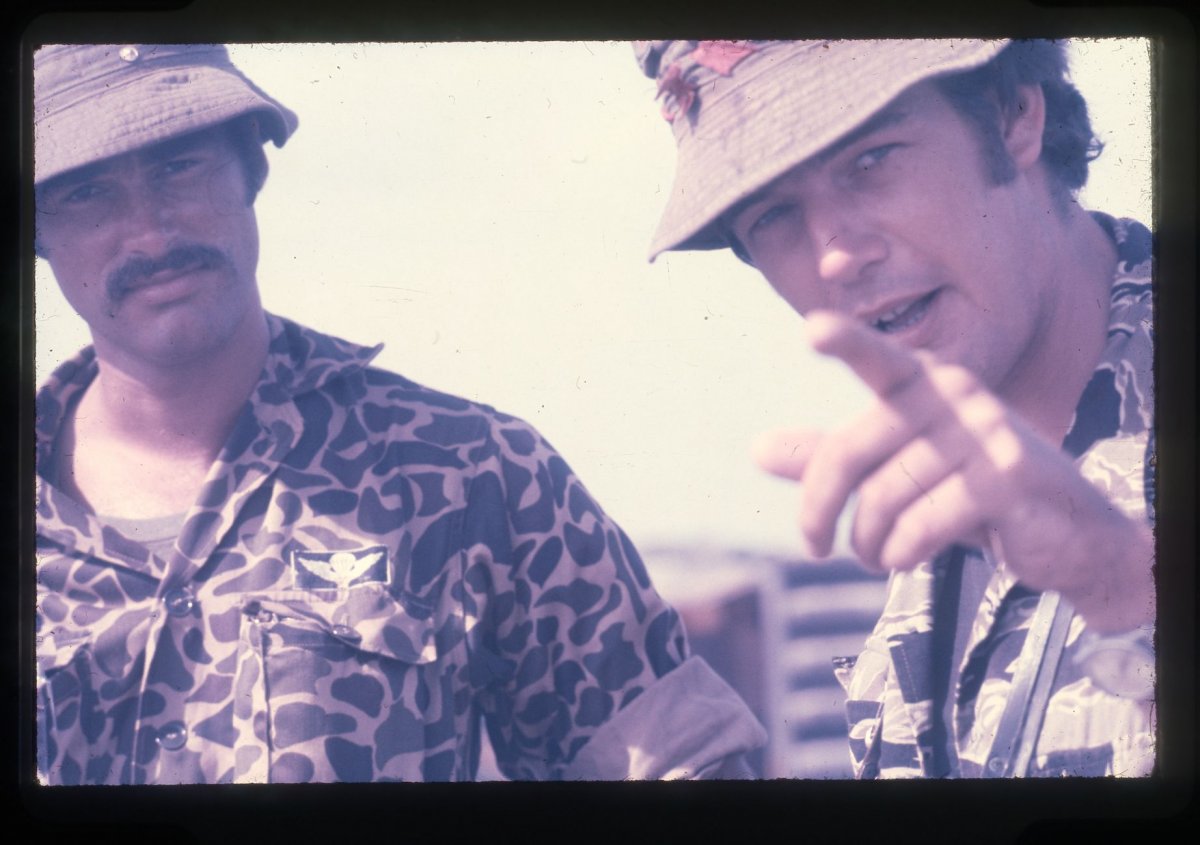

It was the youngest group of journalists to ever cover a conflict; Jack Laurence of CBS figured out the role at 26. Having said that, war is a young man's game. Old men send young ones to die. The Vietnam experience, including what occurred in Laos and Cambodia, would claim the lives of 135 photojournalists. The Robert Capa Gold Medal for bravery celebrates the famous photographer who was killed by a land mine in Tonkin on May 25, 1954. His "Death in Spain" and D-Day pictures set a benchmark we all strive to achieve.

It was the first time that images could stream almost live back to the presses and living rooms of the world. The first time there was an uninterrupted, save for technical issues, uncensored daily photographic record. We were shooting it in both color and black-and-white. Initially, your color had to vanish unseen to labs a world away on at best a Boeing 707, taking 24 hours to reach New York from Saigon. Maybe it is that color—the colors of photojournalist Larry Burrows of Life magazine, the Sunday supplements—that has come to represent the Vietnam War. The classics, however, are still monochrome; they are the ones that say "Vietnam." We all have 10 frames in our mind's eye, something that can't be said of other conflicts before or since. It was a war defined by its photography.

Where else could a debutante, a green shooter, be able to travel with the grand masters of our craft? Henri Huet had the patience to teach me the darkroom; Eddie Adams let me tag along; Horst Faas bought my first freelance pictures; and Larry Burrows had to show me how to load my first Leica, the result of my first Life spread. In 1965, Life paid $300 a page for black-and-white and $600 for color, a small inspiration to pack at least two bodies into the field. It was hot and wet, hot and dry. It was tough terrain and long slogs for an occasional rewarding frame when the proverbial ordure hit the rotors. It guaranteed the erosion of your gear, not to mention your body.

We were young, and the GIs, the grunts in the field, dug that we were their age. We confounded them by expressing our urge to cover their existence. Even in the most stressed, horrific death struggles, there was almost a tangible need to be documented emanating from the stricken GIs. Asians remained more stoic about their fates. It was the most profane of moments that you hungered to capture—feeling the interrogation of your fate at the same time as the fear of the end, of getting horribly wounded, of never being again, of the unknown. There was solace in going out into the field with a mate, a fellow journalist or photographer, and you never got in each other's frame. This was not a competition, and you willingly took the others' film back to their bureau (after having dropped your own at the lab first). At key happenings, you would find a handful of the hardcore you worked beside in the field.

During Mini-Tet at the Y-Bridge, I remember Philip Jones Griffith, Larry Burrows, Shimamoto San and myself standing around the back of a fire brigade truck wherein the mini-gunned body of a daughter of an abattoir worker was being keened over by her younger brother. And there's not one selfie of any of us. Mini-Tet was a bad time for the bao chi—Vietnamese for "journalist." Six were killed and eight wounded. I had arrived back in the country penniless a week earlier, seeking the thrill of gracing Life's pages, coming to rest on the coffee tables of the West and the dunnies of the outback.

That was the strength of those images—you kept on flicking back through them, finding familiars, friends, good feelings and fear. Now, although deluged with great imagery, photography is screen-born and temporal, flicking on, deleted, entropied, lost. Today, 40 years on, I can still return to a negative or transparency, emulsion only slightly time-worn, and reprint a glowing image that still brings an inner joy and revelation. This is not a lament, only a reality. We who survive have one foot in nostalgia. One of the strongest, enduring band of brothers and sisters who believed to the end that their photographs made a difference. It was ungarnished truth, in-your-face reality made more memorable by the lick that each shooter put upon his or her images. It was a war you lived in, not just one you visited. It sucked you into the beautiful country—its women, its food. The '60s additive of sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll. Cross cultures. Surfing at China Beach and peace prayers on an island midstream the Mekong. One hour in an ambush, the next reclined over a soothing pipe or propped at a bar with a dollar beer, retelling the last escapade as a temporal catharsis. The big rush came later when you could flash a spread in a magazine, the ultimate tangibility, that brought on other day rates of assignment. Back then, $100 bought a lot, when film was a buck a roll, a carton of ciggies, $3, Courvoisier, $6, and a Nikon F body, $95, in the PX.

To be in and out of combat at the drop of a helmet was the convenience of the chopper, the ubiquitous Huey, proffered to a generation of shooters accustomed to taxis. Riding them, shooting from them, inserted out of them, resupplied and rescued by them. A defining experience that made it a trademark of that distant conflict. For it is now 40 years since Saigon got renamed Ho Chi Minh City, after it was liberated on April 30, 1975. Finally, 30 years of conflict was over. Defined by Hu Van Es's chopper picture and Fifi de Mulder's one of the tank plowing through the palace gates. Both now deceased.

Where else was it possible for a PIO (Public Information Office) photographer to DEROS (Date Eligible for Return From Overseas) from the army, go freelance and win a Capa gold medal, like John Olson? Where could you jump ship with a camera like Dana Stone and grace a Time cover? Where could you arrive a B-grade film star and become a myth like Sean Flynn? Your dream and fantasy could be realized when you had the temerity to keep going out, often going back to units—ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam), Korean, American or Aussie—with whom you had a familiarity, a prior engagement. American units habitually notified their favorites about upcoming operations, hoping to draw you out to another conflict and proof of winning the war.

The photographers on the other side shot it to prove to their people that this was their glorious struggle and worth every life and sacrifice. They were spiked by editors in the West dissuaded from running any sympathy or support for the "evil communist mob." Now it can be appraised as the photojournalistic entity that it is: 75 of them perished, not all their remains recovered. Only today are they being honored. Vietnam is still unsure where its sympathies lie over its coverage. It likes to see ours in the light that it abetted the end of the war, its victory.

Maybe the only way to remember it is in the eloquence of their images in Requiem, a tribute to the 135 photographers who died from all sides. Fourteen of ours are still missing. Prominently among them, Sean Flynn, my brother and mate who disappeared April 6, 1970, captured by Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge troops in Cambodia. The quest to establish his and the others' fates led to the establishment of the IMMF (Indochina Media Memorial Foundation) and the inception of the book and its subsequent exhibition. My co-helmsman was the Pulitzer and double Capa winner Horst Faas, who was a photo editor for the AP based in London when our synergy reemerged. A copy of Requiem was buried at the crash site on the Ho Chi Mihn trail of the chopper that took the lives of Henri Huet, Larry Burrows, Shimamoto San and Kent Potter. Probably the worst day in photojournalism. Mentors and mates missing forever, their legacy is now in those pages. Images that will endure history, making the strongest anti-war statement. For all good war pictures have that effect.

Postscript:

The irony is that the only place to visit Requiem now is at the War Remnants Museum in Hoi Chi Minh City, albeit the Cambodia chapter has somehow politically been obviated from the entire show, which was donated by the Indochina Media Memorial Foundation and funded by a group of CEO veterans in Kentucky.

Tim Page's career spans 50 years of documenting conflict and its aftermath. He is the founder of the Indochina Media Memorial Foundation and co-editor, with Horst Faas, of Requiem, which commemorates the 135 photographers who were lost during the wars in Indochina. He now lives peacefully in Brisbane, Australia.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.