While city dwellers may not love sharing their streets with pigeons, to say that they find themselves in direct competition with one another may be a bit of an overstatement. But that was exactly the case for 15 people in a lab in Germany, who found themselves pitted against a group of Columbia livia pigeons.

In this experiment conducted by a group at Ruhr-Universitat Bochum, which compared pigeons' and humans' ability to switch between tasks, it was the birds that came out on top.

The idea for the experiment, researcher Christian Beste told Newsweek, started from the well-established fact that birds, including pigeons, lack a neocortex, layers of tissue in the brain thought to play a role in higher functions. It was previously believed that animals without a neocortex couldn't handle higher-order cognitive processes, but study after study has begun to show that, neocortex or no, birds do pretty well.

The humans and birds were set to the same task: respond to a light by pressing a key on a keyboard. In some trials, they were made to alternate between this task and another. In others, once participants started to respond, they were instructed to stop the task altogether and redirect their attention.

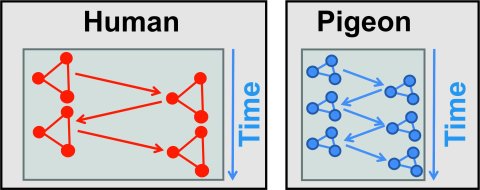

When it came to "multitasking"—switching immediately from task to task—the pigeons performed just as well as the humans. When there was a time delay between the end of the first task and the beginning of the second task, results clearly favored the pigeons.

"They are way better at switching between one task and the other than humans," Beste said.

Why the difference? Beste and his colleagues think the way the brains of pigeons are organized has something to do with it.

While birds lack a neocortex, the distance between neurons in pigeons is much shorter than in humans. That, Beste's group believes (they plan on testing this directly in further experiments), could explain their better reaction time.

In the wild, Beste says, that may be an advantage. If a pigeon is pecking away at a piece of corn and it happens to see a predator, the time switching between eating and flying away can mean the difference between life and death. Beste's response also calls to mind the pact between pigeons and humans described in Seinfeld (in the cases where that predator is a speeding car).

On a cognitive level, Beste says, there is no such thing as multitasking. Beste was clear on the distinction that any responsible person would make to a friend who insists he or she can fluidly text while driving, browse the web while walking, or tweet while working. While we may experience these instances as doing two things at once, we are actually toggling between two tasks very quickly.

Beste says that's underscored by the fact that, while the pigeons outperformed the humans when there was a time-delay between tasks, there was no difference between the two groups when it came to 'multitasking.'

So, pigeons (forget for a moment that they lack the capacity for written language) should by no means attempt to text and fly.