Just east of the Anacostia River's snake-like path through our nation's capital lies a neighborhood far removed from the wheeling and dealing of Capitol Hill. Anacostia, while a historically significant area, has long been fraught with gun violence. It's an area of Washington, D.C., that Congress may have forgotten, but it hasn't eluded capitalism's grasp: A Wal-Mart will soon be erected in the place of a structure known as Community of Hope, a resident observes. The same person says that one of the main thoroughfares, Benning Road, has been nicknamed the "pathway of death." Meanwhile, the Department of Homeland Security is moving into what was once a mental institution.

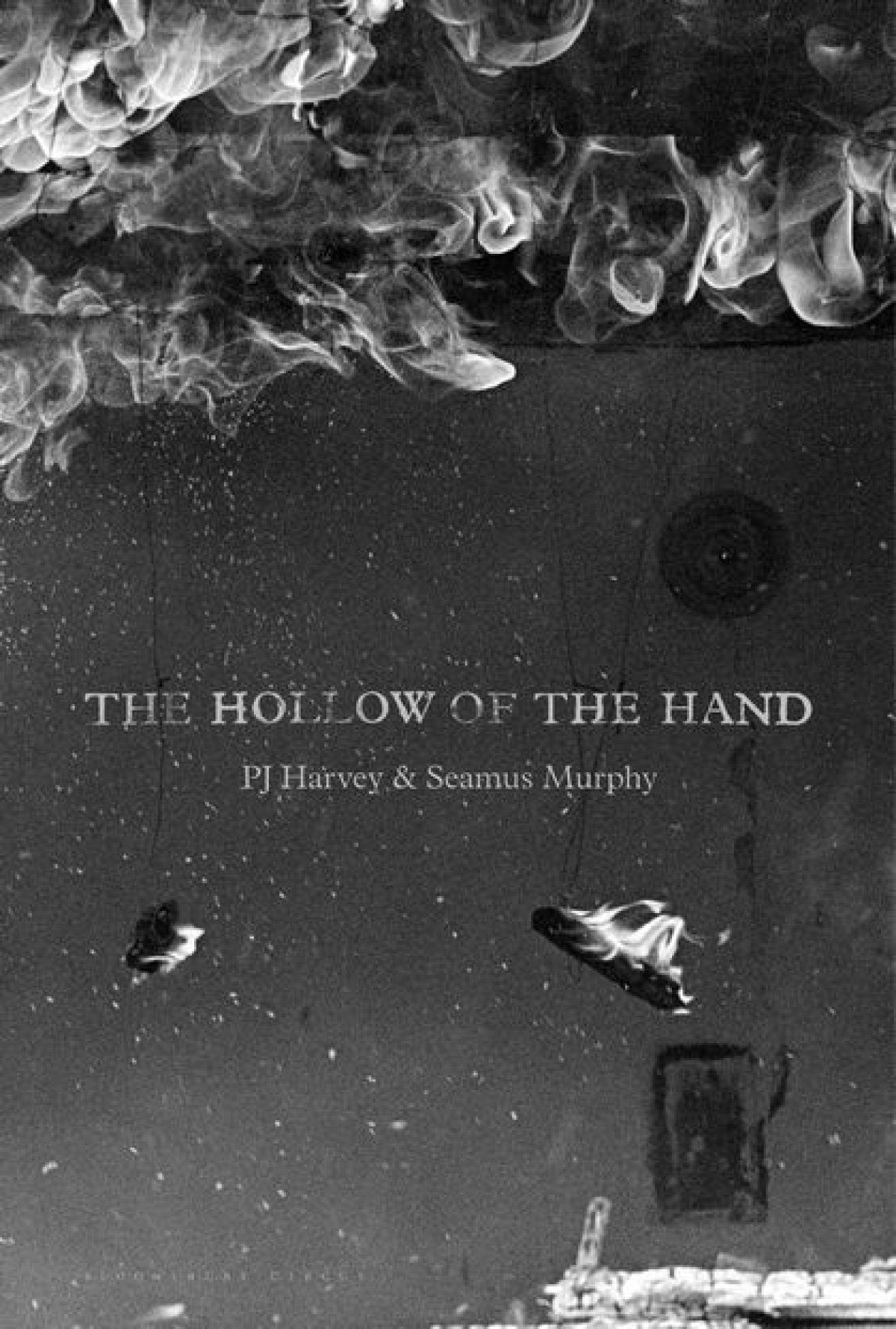

These competing forces are inscribed in Polly Jean Harvey's new book of poetry, The Hollow of the Hand, which traces the prolific English musician's travels through Washington, Kosovo and Afghanistan from 2011 to 2014. The book is a collaboration with Seamus Murphy, a war photographer and filmmaker whose emotive work captures the human consequences of battle, sorrow and sparse moments of intimacy. The exploration of the hollowness that war leaves behind, stateside and beyond, informed not only The Hollow of the Hand, which is out Tuesday, but also Harvey's forthcoming studio album, her ninth, which probes these parallel themes of globalization and the cyclical nature of violence.

Alongside another river, the Thames, Harvey set foot in a nondescript studio space in London's Somerset House in early 2015 to record her not-yet-titled new album. The project was unusual in part because of where it was recorded: The notoriously private Harvey had stepped out of her secretive space and directly into the public eye. Which is why I went in mid-February to the bowels of Somerset, where I peered from behind a glass pane at Harvey and her band recording the follow-up to 2011's Mercury Prize–winning Let England Shake.

Here, a lucky handful of revelers watched and heard everything that went on inside the glass box where Harvey and her band were sequestered with their music. Thanks to a one-way mirror and some sound insulation, the band couldn't see or hear the crowd. The experience of the observers varied depending on when they chose to attend, as the state of the band shifted and stages of recording progressed throughout the process.

When I arrived, the band was in medias res of a throttling, percussion-heavy number. Harvey stood at the center of the room—slight, serene—clad in a muscle shirt and black pants, surrounded by eight studio musicians. Her producers and musical compatriots, John Parish and Flood, sat across from her on a white couch. Murphy, who had contributed videos to Let England Shake, was there with his camera on, though I sensed he had long become part of the scenery. At that moment, Harvey was laying down a vocal track, and she went back and forth with Flood on whether to use the more "punk" take. Everyone in the room bobbed in a collective headbang to the chorus. Months later, I realize that it's cribbed directly from the very Hollow poem about Anacostia, titled "Sightseeing, South of the River." The song is titled "Community of Hope," and its chorus now rings familiar: "They're gonna put a Wal-Mart here."

Harvey's monthlong Recording in Process project, presented by Artangel and Somerset House, was something between an art installation and a deliberately placed peephole. It worked like this: From mid-January to mid-February, 50 fortunate Harvey worshippers at a time were whisked into a dungeon-like chamber at three different intervals throughout the day to briefly experience the minutiae of the making of an album before it's mastered, pressed on vinyl and packaged for your convenience. I knew none of these people, fans ranging from bespectacled 30-somethings to snowy-haired older couples, but it felt like we were going to take part in some kind of illicit ritual together.

Harvey has said what's in her immediate proximity is key to her process. This whitewashed room was filled (but not cluttered) with instruments: a bouzouki, a couple of saxophones, guitars, bass guitars, autoharps. The space itself was pristine, save for a series of eerie drawings tacked above the soundboard: two-headed wolves, birds circling in an ominous sky, goats being led to slaughter. Harvey drew these pieces in Afghanistan, which the Guardian's Sean O'Hagan noted may set the tone for the record as a thing of global anxiety, violence and destruction. Judging from the images and songs, the album is likely a spiritual sequel and an expansion of the themes explored the politically bent Let England Shake.

Everything in our world is exposed, yet this experiment somehow feels even more voyeuristic than pornography. Recording in Process was purposely invasive. It lay bare the interactions between players and producers, and, however unnatural, explored the "flow and energy of the recording process," as was said in a press release. That flow involves intimacy, awkwardness and occasional stretches of boredom. The project displayed the recording process as it actually is, which is pretty unglamorous. One could easily say Harvey has hitched onto the contemporary trend of performance artists doing activities in public such as sleeping, reading out lists or playing metal music while trapped in boxes. Still, Harvey has a well-publicized distaste for dissecting her music or giving interviews (she declined to speak for this piece).

But as she told Michael Morris, co-director of Artangel, the project was meant to be discomforting: "It's a situation that I have not been in before, and I'm not sure how it'll affect us. Will it make us step up our playing even more through the awareness that there may be an audience? Will it make us self-conscious in a way that could be really useful to the recording? I don't know the answers yet." Despite all the self-consciousness, the approach proved useful. For one thing, Harvey and the band sped through the recording. "We had earmarked another four to five weeks in case she needed it," says Morris, speaking to me over the phone. "But she actually got through the whole very quickly." I suspect that being observed might have had something to do with it. That leaves little time for the overthinking that often happens when one is alone.

Critics and audiences often speak of Harvey the way we do of natural disasters: with roars, silences, thunders. "There is nothing weak about this music," wrote NME of Harvey in the 1990s. "Its deep, unholy sexual charge stems back from the feelings of terror James Brown and Jerry Lee Lewis were able to incite the Godfearing Fifties, and it rightly offends those who need offending most." I've never doubted her confidence for a second, given her unapologetic performance style, clever subversion of gender in song (a gendered realm) and how consumed she is by pushing past her limitations. Who else would task herself with learning to play and performing on an album only instruments she didn't know, as Harvey did on 2007's stark White Chalk?

Perhaps exposing herself completely during the Recording in Process experiment was a way for Harvey not only to contend with culture's increasing desire for invasion but also to assuage her anxiety when it comes to spaces. This theme is everywhere in her work, from the fear of being trapped by walls in Rid of Me's "Me-Jane" to the dozens of examples within the poems in Hollow. In between Murphy's gripping photos of villagers, blue hands and burning buildings, Harvey grapples with being respectful of spaces and traditions. In a poem about Afghanistan, "The Guest Room," she writes of her anxieties as a guest in a place where the host can't kick you out: "Children bring us tea and bread. / I wish we had brought gifts. / I hope we know when to leave."

I put the book down after reading this line. It made think of what we demand of Harvey, as fans buying her albums and books, and as guests in the house she creates. We want to know how she does what she does. This fascination and expectation aren't unique to her: There is the sense that artists, whether PJ Harvey or Paul McCartney, must consistently provoke and challenge us intellectually, spur a change of heart or head, blow our minds and rock our bodies. We expect them to straddle the tenuous line between crowd-pleaser and trailblazer. So when artists dare to challenge and potentially scare themselves, we are merely spectators leaning on the glass, trying to find truth from the reflection.

While there's no lack of depth in her music, the little we know of Harvey as a person is the scraps she gives us. That's why this rather unsexy-sounding installation sold out in minutes. It's why I feverishly read the loose observations and visceral details constituting The Hollow of the Hand, cover to cover, practically in one sitting. Beyond the glass and on the page, she's both closer and farther away from us than she's ever been.

This past weekend, Harvey and Murphy celebrated the book's release at the London Literature Festival at Southbank Centre and performed 10 cuts from the new album, one that the London Evening Standard predicted would be "hard to forget." The globalization-centric music, combined with The Hollow of the Hand, won't let fans really know Harvey. We never will. But these two pieces are meant to give us a deeper insight into ourselves, how we can contend with the difficult questions of the world and what we demand of its people. If nothing else, there's hope in that, at least.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Paula Mejia is a reporter and culture writer. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, Rolling Stone, The A.V. Club, Pitchfork, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.