In Baldwin County, Alabama, an award-winning plan to provide guidance for private-sector developers was spiked—it was, constituents complained, part of a United Nations plot to end property rights, impose communism and force locals onto rail cars heading to secret camps. When the blueprint was voted down, residents cheered and sang "God Bless America." Every member of the zoning commission resigned in disgust.

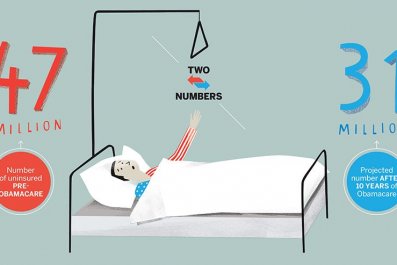

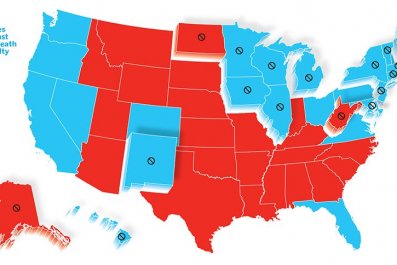

A federal proposal that would have paid physicians for time spent discussing elderly patients' medical and personal priorities in their final days of life was shelved. Some conservatives, led by former Alaska governor Sarah Palin, slammed the idea as creating "death panels" of bureaucrats to decide who would live and who would die. With the rejection of the plan, which had been supported by geriatricians, oncologists and advocates for senior citizens, the aged in the United States now only hear their options for resuscitation, pain control and religious support if their doctors provide the counseling for free.

In 2008, no one in America caught measles and 13,278 people contracted whooping cough. By 2013, measles infected at least 276 people in the U.S. and there were more than 24,000 cases of whooping cough. Medical experts attribute this trend to declining numbers of people being vaccinated, in large part fueled by a belief that doctors and pharmaceutical companies are hiding the dangers of immunizations to protect profits, even though earnings in this niche are so comparatively small that six out of seven companies have dropped out of the business in the past 35 years. Now, because of this false belief advanced by scientific frauds and celebrities, vaccine-preventable diseases that were once on the brink of extinction are roaring back.

George W. Bush murdered thousands by orchestrating 9/11. Barack Obama is a Kenyan national and holds the presidency illegally. Education standards developed by state governors are part of an anti-Christian communist plot that will turn children gay. Unemployment rates and the reported numbers for Obamacare sign-ups are lies engineered by the White House. Water fluoridation doesn't prevent cavities in children and has been adopted for a range of nefarious purposes. And on and on they go.

Conspiracy theories have been woven into the fabric of American society since before the signing of the Constitution. But what was once dismissed as the amusing ravings of the tin-foil-hat crowd has in recent years crossed a threshold, experts say, with delusions, fictions and lunacy now strangling government policies and creating national health risks. "These kinds of theories have the effect of completely distorting any rational discussion we can have in this country,'' says Mark Potok, a senior fellow at the Southern Poverty Law Center who recently wrote a report on the impact of what is known as the Agenda 21 conspiracy. "They are having a real impact now."

Experts say the number and significance of conspiracy theories are reaching levels unheard-of in recent times, in part because of ubiquitous and faster communications offered by Internet chat rooms, Twitter and other social media. "Conspiracy narratives are more common in public discourse than they were previously,'' says Eric Oliver, a professor of political science at the University of Chicago who has published research on the phenomenon. "We seem to have crossed a threshold."

The fears about Agenda 21 are a prime example. The name refers to a nonbinding statement of intent signed in 1992 by President George H.W. Bush and 177 other world leaders. The idea was simple: Under the auspices of the U.N., those countries expressed their interest in managing urban development and land-use policies in ways that minimized the impact on the environment. At the time, mainstream conservative and liberal politicians considered the concept to be fairly inconsequential.

No more. Extremist organizations latched on to Agenda 21 as an attempt by the U.N. and the "New World Order" to seize private property to advance the causes of communism and to crush all dissent. Death maps will be created to determine where people will be allowed to live, some of the theories go. Trees will be given the same rights as humans. Electricity companies will conduct surveillance on customers.

By 2012, the Republican National Committee—overlooking that a Republican president had signed Agenda 21—adopted a resolution slamming the document as an "insidious scheme" designed to impose a "socialist/communist redistribution of wealth." That language was toned down by the time of the Republican National Convention, but wild claims about Agenda 21 survived, saying the barely financed, unenforceable declaration was "insidious" and "erosive of American sovereignty."

Today, the Agenda 21 conspiracy is raised around the country when local zoning boards—many of whom have never even heard of the U.N. statement—attempt to adopt development plans that control willy-nilly construction while considering environmental impact. That Baldwin County proposal was felled by fears of Agenda 21. A highway construction project in Maine designed to ease traffic congestion was abandoned. Same with an oyster bed restoration plan in Virginia and a high-speed-rail proposal in Florida. The construction of bike paths—bike paths!—has been attacked by locals waving signs about sinister international conspiracies.

Even the recent controversy involving Cliven Bundy, a Nevada rancher who refuses to pay fees required under law for his cattle to graze on federal land, has been linked to the U.N. "You need to investigate U.N. Agenda 21, as this is what the Obama administration is following in order to steal your land and rights via zoning changes,'' an Idaho resident wrote to her local newspaper, the Coeur d'Alene Press, about the Bundy case. "The U.N. goal is to remove ALL private property rights, as they are considered 'unsustainable.'"

The letter wasn't tossed into the trash with the other bizarre, conspiracy-laden missives that arrive at news organizations every day. Instead, it was printed in the paper under the headline "BUNDYS: All part of U.N. Agenda 21." Never mind that grazing fees on public lands were established in 1934, almost six decades before Agenda 21, and that other ranchers hold 18,000 permits without any global intrigue involved.

These kinds of fearful convictions are not limited to one side of the political debates, research shows. "Who believes in these? Everyone," says the University of Chicago's Oliver. "Conspiracy theories go across the ideological spectrum."

Take the theories about the George W. Bush administration. There have been claims and suggestions that Bush used the 9/11 attacks—or even engineered them—as a pretext to engage in wars and increase the state security infrastructure; that his vice president, Dick Cheney, orchestrated the Iraq War to shovel millions of dollars in reconstruction contracts to his former employer, Halliburton; and that the administration rigged the 2004 election through fraud in Ohio. And while these ideas have been put forward by plenty of regular citizens, they have also been advanced by national political figures: respectively, Keith Ellison, a Democratic congressman; Senator Rand Paul, a Republican associated with the party's libertarian wing; and Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the son of Bobby Kennedy, who is now a liberal radio talk-show host.

Indeed, the prominence of some of the conspiracy theorists attacking the Bush administration is a reflection of a more disturbing trend: national political leaders who advance tales of secret schemes and treachery without a scintilla of evidence. Many politicians lent support to the idea that Obama was hiding his birth certificate, a central tenet of the claim that he was born in Kenya. Among those quoted in news articles making those statements are Senator Richard Shelby, then-congressman Roy Blunt, then-representative Nathan Deal and others. Former representative Cynthia McKinney was a proponent of 9/11 conspiracy theories. Senator Ted Cruz has said Agenda 21 involves attempts to abolish golf courses and paved roads.

Prominent business executives and pundits also push unsupported claims about conspiracies. Jack Welch, former chairman and CEO of General Electric, proclaimed that declining unemployment figures released by the government before the 2012 election were fraudulent. Dick Morris and other political commentators advanced the idea that polls showing Obama winning the 2012 election were the result of a conspiracy among polling firms. Jesse Watters, an interviewer and producer at Fox News, said that when numbers from the White House showed high sign-ups for health insurance under Obamacare, the administration was "straight-up lying."

Experts who study conspiracy theories are uncertain as to why so many national figures are now openly advancing suspicions of sinister plots. "There are certainly people who will take things further than they honestly believe,'' says Dr. Michael Wood, a lecturer at Britain's University of Winchester who teaches the psychology of conspiracy theories. "But it is also quite possible that these ideas about conspiracy theories have taken hold in top levels of politics. It would be strange if politicians were completely immune to this."

Often, when prominent individuals suggest that their political opponents are engaged in nefarious activities, they hedge by saying they are merely attempting to raise questions that should be considered—a way, experts say, of starting conspiracy theories. "One of the most common ways of introducing a conspiracy theory is to 'just ask questions' about an official account,'' says Karen Douglas, co-editor of the British Journal of Social Psychology and a senior academic who has researched conspiracy theories at Britain's University of Kent. "It's quite a powerful rhetorical tool because it doesn't require any content, just the introduction of doubt about the official story."

But accusing political opponents of serious wrongdoing based on unsubstantiated nonsense plays havoc with social discourse. When each side attacks the other based on wild theories—calling them terrorists, anti-American, murderers, racists and the like—the tribal divisions cripple basic governance.

"The reason we should worry about conspiracy theories and misinformation is that they distort the debate that is crucial to democracy,'' says Brendan Nyhan, an assistant professor in Dartmouth's government department who has conducted research on conspiracy theories. "They divert attention from the real issue and issues of concern that public officials should be debating."

That is what has happened with the issue known as Common Core standards in public education. They were developed by the National Governors Association, working with an organization of state school superintendents, with the intent of advancing educational standards and identifying the math and literacy skills that every student at each grade level should have. The standards are now being implemented in 44 states.

There are strong reasons to support or oppose Common Core, and whether it is the right way to improve the nation's school system is open for debate by well-meaning participants. Legitimate questions exist about whether the standards have been appropriately tested or whether teachers should be judged based on the performance of their students on Common Core exams. Unfortunately, that discussion has been derailed by conspiracy theories about the standards, built on falsehoods, misunderstandings and beliefs in ominous, secret plots.

"It is communism," Glenn Beck, a prominent conservative commentator, said on a television program last year when speaking about Common Core. "We are dealing with evil. And there comes a time where you have to just say what it is, and it's evil.''

Again, those types of accusations have found their way into the political process, along with false allegations that the standards were assembled by the Obama administration, a fiction that has led opponents to deem them "Obamacore." According to a just-released report from the Southern Poverty Law Center, the conspiracy theories flowed in April at a hearing before Alabama's Senate Education Committee about legislation to allow school districts to reject Common Core. "We don't want our children to be taught to be anti-Christian, anti-Catholic and anti-American," the report quotes Terry Bratton, a Tea Party activist, as saying. "We don't want our children to lose their innocence, beginning in preschool or kindergarten, told that homosexuality is OK and should be experienced at an early age and that same-sex marriages are OK."

Common Core teaches none of those things. In fact, it pretty much teaches nothing—there is no curriculum, no imposed method of learning, no books that must be studied. Indeed, the only materials every student is expected to read in Common Core are the Preamble to the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the Declaration of Independence and Abraham Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address.

Common Core is about skills, not substance. For example, a reading standard for fourth grade says students should be able to "determine the main idea of a text and explain how it is supported by key details." While the standards do include a list of books as examples of what students might read to help them sharpen these abilities, none of them are required. A teacher or local school district can choose all, some or none of those suggestions and still be part of Common Core.

So is Common Core a worthwhile nationwide undertaking? America might never know. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, about half of the more than 200 bills about Common Core filed by legislators around the country would slow or stop the adoption of its standards.

Conspiracy as Contagion

Where does a conspiracy theory come from? Often, it is generated by fringe groups whose information is picked up by more credible sources, until it eventually reaches the mass media. The Southern Poverty Law Center's Potok cites the example of what is known as the "Aztlan Conspiracy,'' which holds that Mexico is secretly planning to invade the United States and retake seven states in the Southwest. The law center traced the theory to a radical anti-immigration group of about a half-dozen Americans. The idea was picked up and promoted by larger and larger groups, until finally Lou Dobbs, the well-known broadcaster who was then working at CNN, mentioned it.

"That's how it goes,'' Potok says. "It starts with a fringe group, and, before you know it, it's on national television, which makes it incredibly difficult to have a serious conversation about immigration."

While the growth in the number of news outlets has helped spread conspiracy theories, it doesn't compare to the impact of social media and the Internet, experts say. With these technological advances, people who believe in a conspiracy can seal themselves off with like-minded people online, creating a situation in which no corrective information is heard but the theories can still spread. "If you have social networks of people who are talking with one another, you can have a conspiracy theory spread in a hurry,'' says Cass Sunstein, a professor at Harvard Law School who wrote the book Conspiracy Theories and Other Dangerous Ideas. "It literally is as if it was contagious."

While some may dismiss conspiracy theorists as ignorant or unstable, research has shown that to be false. "The idea that only dumb people believe this stuff is wrong,'' says Dartmouth's Nyhan. "The reality is that more knowledgeable people can fall victim to these claims as a way to confirm what they already want to believe."

Researchers agree; conspiracy theories are espoused by people at every level of society seeking ways of calming the chaos of life, sometimes by simply reinforcing convictions. "The world around us can feel more disordered and chaotic for various reasons,'' Nyhan explains. "Conspiracy theories provide a way to restore feelings of control and order.''

The research on those who buy in to conspiracy theories can be perplexing. For example, one study showed that a person who believes Britain's Princess Diana was murdered in 1997 is also more likely to think she is still alive. Those who think that Osama bin Laden was dead before an American SEAL team raided his compound in 2011 are also more likely to be convinced he escaped.

This ability to hold two contradictory thoughts goes to the nature of conspiracy theories and their believers. Psychological research has shown that the only trait that consistently indicates the probability someone will believe in a conspiracy theory is if that person believes in other conspiracy theories.

And the number of people who believe in these often very tall tales is enormous. According to a poll last year by Public Policy Polling, a national firm, 28 percent of Americans believe a secret power elite is conspiring to rule the world through a global authoritarian government, 15 percent believe the government adds mind-control technology to television broadcasts, and 14 percent think the Central Intelligence Agency was instrumental in introducing crack cocaine to America's inner cities during the 1980s.

Similar—and sometimes more extreme—results appear in polls about medical conspiracy theories. Research conducted by professors Oliver and Thomas Wood and published in March by The Journal of the American Medical Association shows that 49 percent of respondents believed in at least one medical conspiracy theory, while 18 percent believed in three or more. The theories best known to the respondents involved cancer treatments, vaccines and cell phones; these were also the ones that saw the greatest numbers of people subscribing to them. Thirty-seven percent believed the Food and Drug Administration was conspiring with pharmaceutical companies to suppress natural cures for cancer, while 20 percent thought that corporations were preventing the government from releasing data showing that cell phones cause cancer or that doctors secretly believe vaccines are dangerous but still want to use them on children.

"Why Deny It if It Wasn't True?"

As with political conspiracy theories, fears about medical plots have real-world consequences. People who more strongly believed in conspiracy theories were significantly less likely to use sunscreen or have an annual medical checkup. Those results held true even after the researchers controlled for socioeconomic status, paranoia and the general social estrangement of the respondents. A similar study conducted by Douglas and Daniel Jolley, a postgraduate researcher at the University of Kent, found that people exposed to conspiracy theories about immunizations were "more reluctant to vaccinate" than those in a control group.

Despite these real-world effects from conspiracy theories in policy, politics and public health, any attempts to combat these suspicions face an enormous challenge: Marshaling facts to demonstrate the falsehood of a conspiracy merely serves to convince the theorists even more that they are right. Put simply, correcting people with data and information will not convince them that they are mistaken. "If people try to correct a false belief, they can simply entrench the belief," says Harvard's Sunstein. "The thought some people have is, Why would someone deny it if it wasn't true? In other words, the denial is proof of the truth of the theory."

For example, a study conducted by Nyhan and others exposed subjects to Sarah Palin's allegations about death panels. Then they were provided with information showing that the statements were not true. Those who disliked Palin, or who liked her but had low political knowledge, readily accepted the correction. But, the report says, showing participants the true information "backfired among politically knowledgeable Palin supporters, who were more likely to believe in death panels and to strongly oppose reform if they received the correction."

This means that some conspiracy theories will simply prove uncorrectable for some people. In fact, even attempting to discuss ways to disprove conspiracy theories can result in new theories. For example, Sunstein wrote an article in 2008 about conspiracy theories and government, and the problem of theorists who are online and speaking only to other true believers. Usually, those people could be ignored, but what about instances where, say, a group of Islamic fundamentalists or other extremists are spreading conspiracy theories that might promote violence? In those instances, Sunstein says, a possible tactic could be "cognitive infiltration of extremist groups," by which he means government agents would enter chat rooms and join social networks where these kinds of dangerous theories are promoted and introduce information intended to raise doubts about them. The agents might disclose their role with the government or not—Sunstein said each option offers different risks and rewards.

And with that, the swarms of conspiracy theorists attacked. Sunstein, they declared, was attempting to squelch dissent, perhaps even helping track down government critics online. In fact, the conspiracists advancing this new conspiracy said Sunstein was obviously some sort of government manipulator, because he was formerly the administrator of the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. He was the disseminator of information from the White House! (Do a search online, or just check the customer reviews on Amazon.com of Sunstein's book. The "Sunstein is an agent of the government" conspiracy is everywhere.)

The truth? Sunstein's job involved no cloak, no dagger. Instead, he was overseeing efforts to reduce paperwork in government and to make sure that regulations were consistent with the law. More bond paper than James Bond. "A lot of these people think I was engaged in some kind of political propaganda and that that was my job,'' he says. "I was just making sure we reduce paperwork burdens.''

Sunstein was not alone. When the Southern Poverty Law Center released its report on Agenda 21, the phone started ringing. "We have been flooded with well-meaning people telling us what utter fools we are for having fallen for the elite's conspiracy,'' Potok says.

So it goes with the endless loop of conspiracy theories. They can't be corrected, they can't be killed. Anyone who attempts to disprove some feverish thought must be involved in the plot. Indeed, most of the experts interviewed for this article agreed on one fact: Once it was published, Newsweek would be accused of being part of the conspiracy.

An earlier version of this article cited cases for whooping cough cases from a non-governmental think tank. Those data do not coincide with figures from the government's Centers for Disease Control. The CDC reports that 13,278 people contracted whooping cough in 2008, compared with a provisional report of 24,231 people in 2013. Broader and completed CDC data more fully demonstrate the magnitude of the growth of the disease. For example, in 2001, the CDC reported 7,580 cases, about the same as it found each year back to 1996. By 2012, the last year with completed numbers, the CDC reported 48,277 cases.