Olivia Koburongo's grandmother was 86 when she died, but she should have lived longer. She spent the months preceding her death in June 2014 in various Ugandan hospitals as doctors tried to figure out what was causing her chest pains, shortness of breath and persistent dry cough. "In the end, they found out she had pneumonia, which is a treatable disease," says Brian Turyabagye, Koburongo's former business partner. "But it wasn't detected in time."

Wanting to understand how her death could have been prevented, the pair—both telecommunication engineering students at the time—researched the disease and discovered that while pneumonia regularly afflicts the elderly, "it was a bigger problem for the kids," says Turyabagye, whose nephew fell ill with the disease last year.

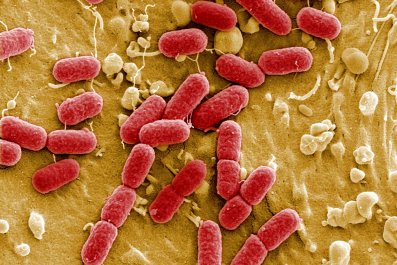

"Over 1 month of age, pneumonia is still the largest killer of children anywhere in the world," says Shamim Ahmad Qazi, a pediatrician who works with the World Health Organization (WHO). In 2015, this figure was close to 1 million—more deaths in children under the age of 5 than malaria, measles and HIV/AIDS combined. "In most cases, it's difficult to diagnose," says Qazi, especially in less-developed countries where X-ray equipment isn't widely available. In Uganda, pneumonia is often mistaken for malaria—the two share common symptoms like fever and cough—but people are quick to assume malaria because the disease has gotten greater publicity in recent years. And yet, according to UNICEF, only 2 cents goes toward pneumonia for every health dollar spent globally.

To combat this "forgotten killer of children," as the WHO calls it, the Ugandan engineers, together with their partner Besufekad Shifferaw, a fellow student from Uganda's Makerere University, have come up with a new tool to improve diagnoses in young children. The prototype Mama-Ope is a biomedical jacket that measures vital signs that can indicate the presence of pneumonia. Once the jacket is fitted snugly over a child's chest, it syncs with an app over Bluetooth, and in under two minutes readings flash up indicating the child's temperature, breathing rate and an assessment of whether the lungs sound normal or not.

"When you've got pneumonia, your lungs—because of the inflammation—get filled with fluid, so you struggle to oxygenate your blood and the body's natural response is to breathe faster," says Keith Klugman, the director for pneumonia at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. "In a community setting, fast breathing is not something that's recognized easily by mothers as a danger sign for a child, and that is something the jacket picks up on."

Related: First aid, by the bullet

Mama-Ope, which means "mother's hope," has been short-listed for this year's Royal Academy of Engineering's Africa Prize, worth about $30,000. The jacket is being tested with volunteer families in Kampala, Uganda's capital, before larger clinical trials are rolled out in hospitals countrywide, most likely by spring. "Eventually, we hope it will be used in the community—something that parents can buy and use to know who is facing the disease so they can be taken for treatment," Turyabagye notes.

Fortunately, his young nephew recovered. "We want to make a difference and to save lives," he says.