A hairless, pale-pink scar runs across the back of 35-year-old Bryce Mickelson's buzz-shaved head, an inch-long reminder of just one of the many brain injuries he's had in his life. At 3, he ran in front of a car and woke up from a coma in the hospital. At 7, a kid threw a rock at his face, ripping it open. At 12, he crashed his bike, his helmetless skull slamming into concrete. Mickelson's noggin has been banged, bruised and split open so many times he can't remember every injury. But he never considered the long-term impact of them until he ended up in jail.

Mickelson has served time for theft, domestic violence, distributing narcotics and possession of a weapon and drugs. His most recent stint inside of the Denver County Jail came after a trespassing charge. "Hey, maybe I'm just stupid," says Mickelson, sitting in a courtyard outside of his cell, his blue eyes droopy and his gray inmate's uniform shapelessly draped like nurse's scrubs over his 6-foot-2-inch frame. He seems to have always had trouble with learning, memory, anxiety and impulsivity. He could have been born this way—or, he admits, it could be due to drugs, which he started using at the age of 8. He's tried everything from marijuana to heroin, to LSD and cocaine. Or, he says, it "could be from a brain injury."

For the first time in his life, Mickelson has been learning about the brain and the many bad things that happen when it's hit over and over again. It all started when a graduate student working under Kim Gorgens, a neuropsychologist and clinical associate professor at the University of Denver, visited him in jail last December. The student interviewed Mickelson about his head injury history and put him through several hours of oral and computer-based tests. Two weeks later, Mickelson received a copy of his neuropsychological report, which showed evidence of repeated blunt force brain trauma. The report outlined his cognitive and behavioral challenges and suggested strategies that could help him cope.

It also qualified him for a traumatic brain injury class for inmates, led by a psychologist. In the weekly sessions, attended by a half-dozen men with many stories of being pummeled in the head with fists and baseball bats, the inmates discuss prompts like: Does having a traumatic brain injury change who we are? What triggers symptoms? And what aids or services can help?

This approach to quantifying a possible connection between brain injury and criminal behavior—and using that data to aide in inmate rehabilitation—arose three years ago. One evening in 2013, Gorgens met up with Judy Dettmer, director of the Colorado Brain Injury Program, and Jennifer Gafford, a staff psychologist for the Denver County Sheriff's Office. After spending some time talking, the women decided to collaborate to measure brain injury rates among the incarcerated and try to provide inmate support programming and services.

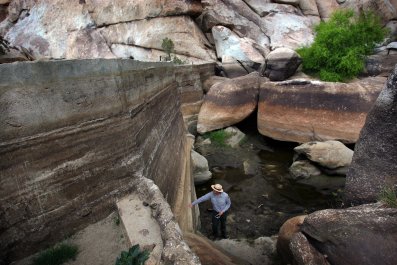

Within two weeks, Gorgens had assembled a team. Over a two-year period, her graduate students assessed 80 inmates in the Van Cise-Simonet Detention Center in Denver, which houses arrestees as they await sentencing. The findings from the pilot study were staggering: Ninety-six percent of inmates screened had suffered moderate or severe brain trauma. It was a sharp contrast to the estimated 6 percent of the general population with similar brain injuries, but it did match up with previous, similar studies from the past two decades. A 2008 study of 990 Minnesota inmates found a rate of 80 percent; a 2006 analysis of 200 Australian prisoners found 82 percent; and a 2007 survey of 107 male and 118 female inmates from six federal prisons found 87 percent.

After the pilot study, the team expanded its traumatic brain injury research to 15 correctional sites, probation programs and courts across the state. The researchers are now screening 1,200 adult inmates and probationers, as well as 500 juvenile offenders, a smaller segment of sex offenders and a separate cohort of veterans who pass through specialized courts. They anticipate the final numbers will be lower than the pilot findings, but based on preliminary results, they still expect the final numbers to be dramatically higher than traumatic brain injury rates in the general public.

Suddenly Aggressive

Convincing the general public to care about the mental health of society's cast-offs is no easy task. But in the past decade, the interplay of brain disorders and criminal behavior has started to become a topic of popular discussion, partly because some athletes and soldiers—society's heroes—have turned criminal, suicidal, emotionally volatile or violent, and a common denominator may be traumatic brain injury.

In December 2012, Jovan Belcher, a linebacker for the Kansas City Chiefs, killed his girlfriend in a murder-suicide. An autopsy of his brain found that he suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, the progressive degenerative brain disease caused by repeated brain trauma and concussions. In a 2015 study, researchers at Boston University found the disease—which is associated with anger, aggression, depression, impaired judgment and poor impulse control—in 131 of 165 former NFL, college and semipro football players, some of whom shot themselves.

In January, Dr. Bennet Omalu, the neuropathologist who discovered CTE in athletes, said publicly that he believes O.J. Simpson, the former NFL running back now serving up to 33 years for robbery and kidnapping, also suffers from the disease. In 1995, Simpson was found not guilty in the criminal case against him for the violent murder of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ron Goldman. He later lost a wrongful-death civil suit brought by their families.

Head injuries early in life can lead to aggressive behavior later on. An eight-year study that followed ninth-graders in Flint, Michigan, into adulthood found that young people who had endured head injuries were more likely to engage in violent acts later—fighting, hurting someone badly enough that they required medical attention or threatening someone with a knife, gun or club—than those who had not. Adults with a history of traumatic brain injuries also tend to enter prison at a younger age, according to an analysis in Brain Injury. A 2009 study of head trauma patients in Maryland found that within three months after a head injury, 28 percent of patients became aggressive.

All of which is why, more and more often, brain trauma is now brought to the court as evidence in criminal cases. Between 2005 and 2012 , more than 1,500 judicial opinions involving defendants have cited neuroscience. But, as Omalu has pointed out, you can't simply blame traumatic brain injuries for criminal behavior—aggression doesn't necessarily lead to criminal acts. Nor can brain injuries be totally unraveled from other risk factors like mental illness and substance abuse. Many inmates are dealing with all of the above. Someone who uses drugs or alcohol is more inclined to get a head injury through a fight, a car accident, a fall. And people with a traumatic brain injury are more likely to abuse drugs or alcohol, either to self-medicate or because regions of their brains that control inhibitions are impaired. "It becomes kind of circuitous," Gorgens says, "where any one of those variables increases the risk of the other problems."

Further, the U.S. legal system doesn't account for the intricacies of a human's dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which contributes to mood, behavior, memory, decisions, impulses and thoughts, and, when injured, can swing a person's personality toward anger, depression or aggression. And the justice system doesn't have a uniform standard for considering changes or differences in areas of the brain involved in emotional regulation—like the amygdala or hypothalamus—which, when impaired, may also interfere with the ability to control yourself physically or emotionally.

With no standard set of criteria on how each court chooses to handle brain data and neurological assessments of defendants, the outcomes vary dramatically. Judges and juries in such trials increasingly must determine for themselves whether a brain injury caused a previously upstanding citizen to commit violent or unlawful acts. Or is the diagnosis simply a convenient excuse? Should it make a difference in punishment?

"The presence of traumatic brain injuries should affect the way we treat incarcerated offenders," says Adam Kolber, a professor at Brooklyn Law School who specializes in neurolaw and bioethics. It may influence the best ways to rehabilitate them, as the Denver group is trying to show, and could be taken into account in determining the severity of sentences. In some cases, traumatic brain injury can make coping with prison life more difficult, which means a sentence that is tolerable for one person could be torment for another, Kolber says.

'Like You're Underwater and Can't Come Up'

Kristi Wall, one of the University of Denver doctoral students who have been conducting the jail assessments for Gorgens, faces 19-year-old Sarah Romero in a small beige meeting room in Denver County on a recent afternoon. Romero smiles nervously, revealing a mouth full of braces. Wall smiles back and tells her to breathe deeply and relax. Holding a stopwatch, she instructs Romero to connect a series of dots on paper in a particular order, "fast as you can." When she's done, questions about her mood flash on the computer screen. Romero doesn't understand some of the meanings.

"Irritab-l?"

"Irritability," Wall says. "It's kind of like worked up. Cranky."

"Enraged?" Romero looks at Wall.

"Very angry."

After the interview, Romero explains how she spent three years with an abusive ex-boyfriend before she got locked up for stealing a "bait car," which cops purposely left for someone to take. Her ex knocked her out at least three times; often hitting her in the face or head, blindsiding her as she walked through the door to their home. Once, she woke up after he hit her and didn't know where she was. "He would beat the shit out of me, punch me in the face, knock me out, choke me to the point when I would pass out. It was so scary, like you're underwater and you can't come up."

Wall, who is focusing her doctoral paper on traumatic brain injuries and gender differences, says Romero's story is not surprising. A 2003 study in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology found that 67 percent of women referred to sexual assault-domestic violence clinics reported symptoms of head injuries caused by abuse. "I would say all but maybe two women that I've tested here have a history of domestic violence, or traumatic brain injury due to domestic violence," says Wall, who has interviewed between two and four inmates a week since August.

The men's transitional unit of the jail, which treats inmates with mental health and other challenges, is a two-floor annex awash in yellow light. It houses 48 inmates, including Mickelson. Two guards monitor the men, who are allowed out of their single-bed cells for about six hours a day to attend Bible study or classes on grief and loss, anger management, parenting and the recently added sessions on traumatic brain injury.

When inside their cells, inmates can peer out through a skinny rectangular window on each door into the center courtyard, which is filled with plastic green chairs and tables with built-in chessboards. In the center of the wing sits a television, around which all of the inmates crowded one afternoon in February for Super Bowl Sunday. Happy to be released from their cells for the entire game, the men spent the afternoon cheering along with deputies when the Denver Broncos scored against the Carolina Panthers. When Broncos linebacker Shaquil Barrett left the game after suffering a concussion in the third quarter, Mickelson and others from his traumatic brain injury class paid close attention.

"A lot of these football players end up with long-term effects," Mickelson says. "They don't even notice they're having all of these problems until later." He can relate to that.

A Head-On Collision

Governments and taxpayers don't traditionally jump at the idea of investing money in criminals, and after news of brain trauma research began to spread, Gafford felt skepticism among law enforcement personnel, whom she interacts with regularly as an inmate psychologist. One said to her, "First it was mental illness, and now it's traumatic brain injury?"

Gorgens began getting angry emails and phone calls to her office at the University of Denver from people chiding her for sympathizing with criminals. "You're trying to get them off," some say. She also received threats. One person said he "wanted to squeeze my head until shit came out of my ears, so that I would get some sense," says Gorgens. "They thought our agenda was to try to overturn convictions, like we were going to excuse the criminal behavior with a magic wand."

But those working in the criminal justice system are beginning to grasp the value of understanding and improving the brains of the incarcerated. In recent years, the Denver government under a mayor's initiative has put more resources into mental health services, hiring psychologists to work with the inmates in the men's and women's transitional units. Two case managers and two psychologists occupy cubicles inside the men's wing, and inmates like Mickelson can just knock on their doors.

The traumatic brain injury research has also helped shape rehabilitation efforts. Many of these offenders will be released on parole, and upon returning to their communities, they will need help navigating that transition to avoid turning to crime or violence again. Upon release, those who qualify are also connected with support staff from the Colorado Brain Injury Program and the Brain Injury Alliance of Colorado.

Over 730 officers in the Denver Sheriff's Department are now going through training to help them understand traumatic brain injury and become familiar with intervention methods that may help them deal with those who have the condition. "This is a paradigm shift," says Gafford. "We really are starting to see a change in officers." In large part, it's because the University of Denver approach is appealing to law enforcement: Maybe analyzing and treating brain injuries could help reduce recidivism and prevent crimes before they even occur. "It's not like you can medicate a brain injury," says Gafford, but "you can help somebody learn how to navigate the world in spite of brain injury."

Amy Blackman, a case manager with the Denver Sheriff Health Services unit, used to be a correctional officer. Now she counsels inmates and talks to them about traumatic brain injury, among other behavioral challenges. Inside of her office in the jail, pencil drawings of owls sketched by a 42-year-old inmate named Scott (who did not want his last name used) hang on the walls. A sign that says "Attitude Is Everything Pick a Good One" hangs next to her computer, inches away from a red panic button, which she can push in case of an emergency, like if an inmate attacks her. She's never had to push it.

"I spent a lot of time not caring about the brain," she says, referring to her seven years as a corrections officer. "It was very black and white. Overall, the philosophy was 'nail 'em and jail 'em.'" When Blackman changed jobs, her perspective began to evolve. Instead of "trying to put the hammer down and hope that they change," she began "looking at the deeper reasons why they act the way they act and thinking about how can we help them."

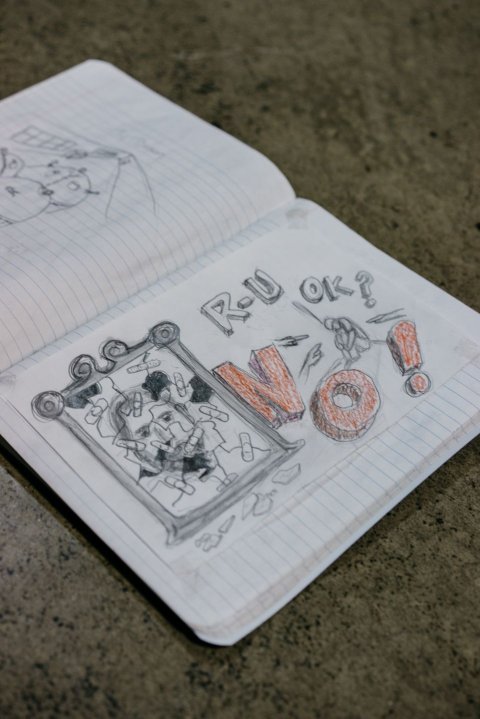

Blackman has seen success with inmates like Scott, who went through the University of Denver neuropsychological exams and enrolled in the jail's traumatic brain injury class. But he didn't need to understand the extent of his possible brain injury-related symptoms. Outside of the jail psychologist's office, Scott flips through the pages of a notebook filled with his drawings and poems:

My hands begin to cramp my legs to shake

You'd think I'm gearing up for war

I can't understand what causes this quake

And down my back the sweat starts to pour.

Scott is constantly agitated, fidgeting, panting, grimacing. Small spaces and interacting with people can stress him out, causing his heart to race. His face and neck drip with perspiration; he rocks back and forth and, at times, paces. Scott began having regular seizures over two decades ago after he was in a car accident on his prom night. "It was a head-on collision, and I went through the windshield and got a fractured skull," he says.

But his head injuries started long before high school. Scott grew up in foster care, and he remembers one home when he was around 5. "The foster father was on a bean farm.… I was big enough to drag a bushel. He had me picking beans. One of his rules was 'You can't eat them.' But they are sweet like crunchy candy. He caught me eating one. He beat the hell out of me and left me in the field. I woke up and wanted to cry. I crawled back to the farmhouse. I slept on the porch. The next day he just grabbed me and dragged me back out to the field to work again. After that, I never wanted to eat a bean again."

Over the years, Scott says, he's been jumped by a gang, hit in the skull with a baseball bat and, in 2009, hit with a crescent wrench. He started using drugs as a child, including marijuana, alcohol, ecstasy, meth and cocaine. He's been locked up for resisting arrest, possession of a weapon and drugs, aggravated assault and burglary, and he's tried to commit suicide.

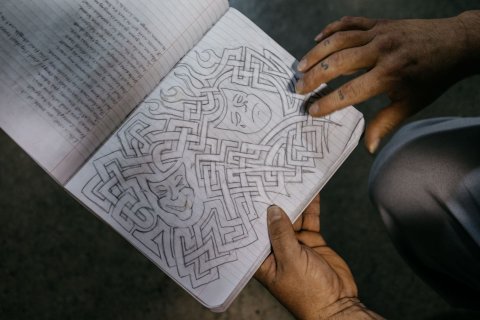

Tests show he may "act without thinking," his neurological report states. It recommends that jail staff repeat instructions and give him extra time or clarification for new information, and offers a list of instructions for Scott to help manage his challenges with memory, following directions, learning, spatial memory and anger.

In addition to the brain injury class, Scott takes psychiatric medications and goes to regular therapy and behavior management sessions. And he pays attention to his emotions in a way he didn't before, calming himself by breathing deeply and channeling his feelings into his writing and art. One of his notebook sketches shows an image of his face reflected in a broken mirror, patched up with Band-Aids.

Scott does not think his challenges stem from his brain injuries alone. That is just one part of the muddle that is his complicated life. But it is one strand, at least, he might one day be able to manage. He hopes to connect with traumatic brain injury support programs when he's released. "I'm learning different ways to deal with it."