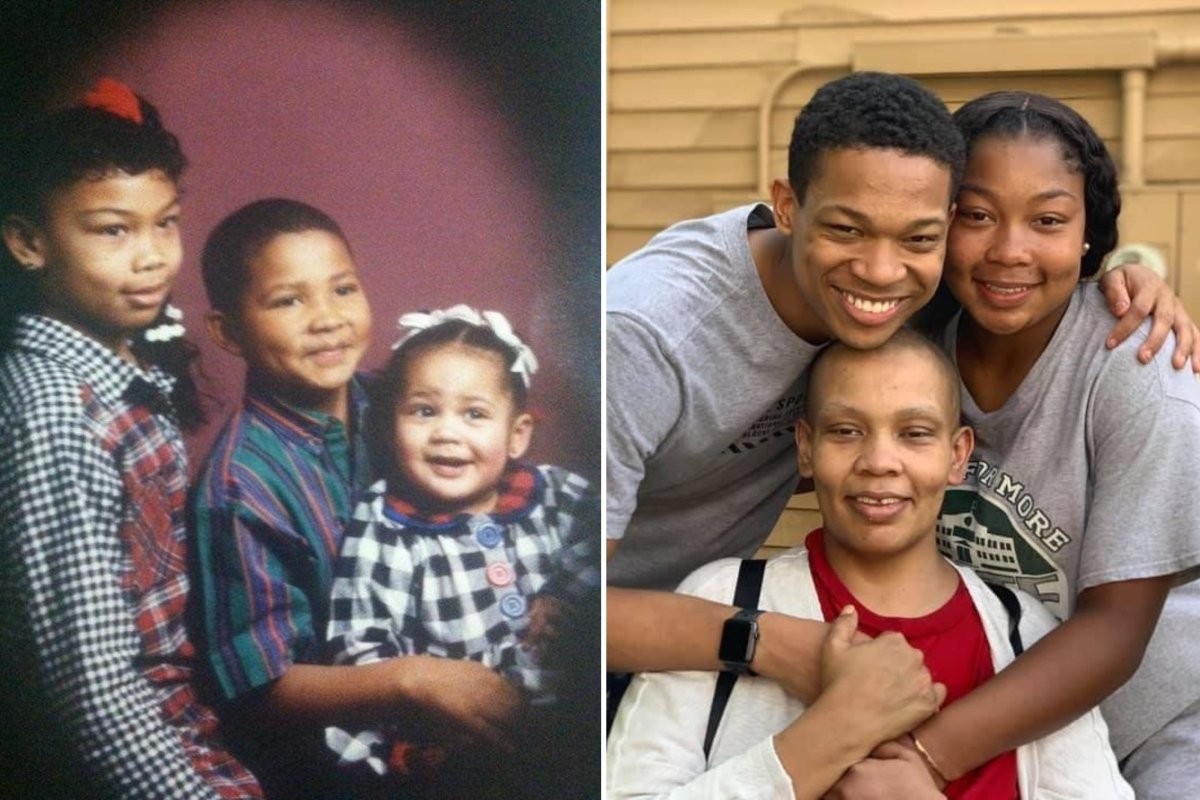

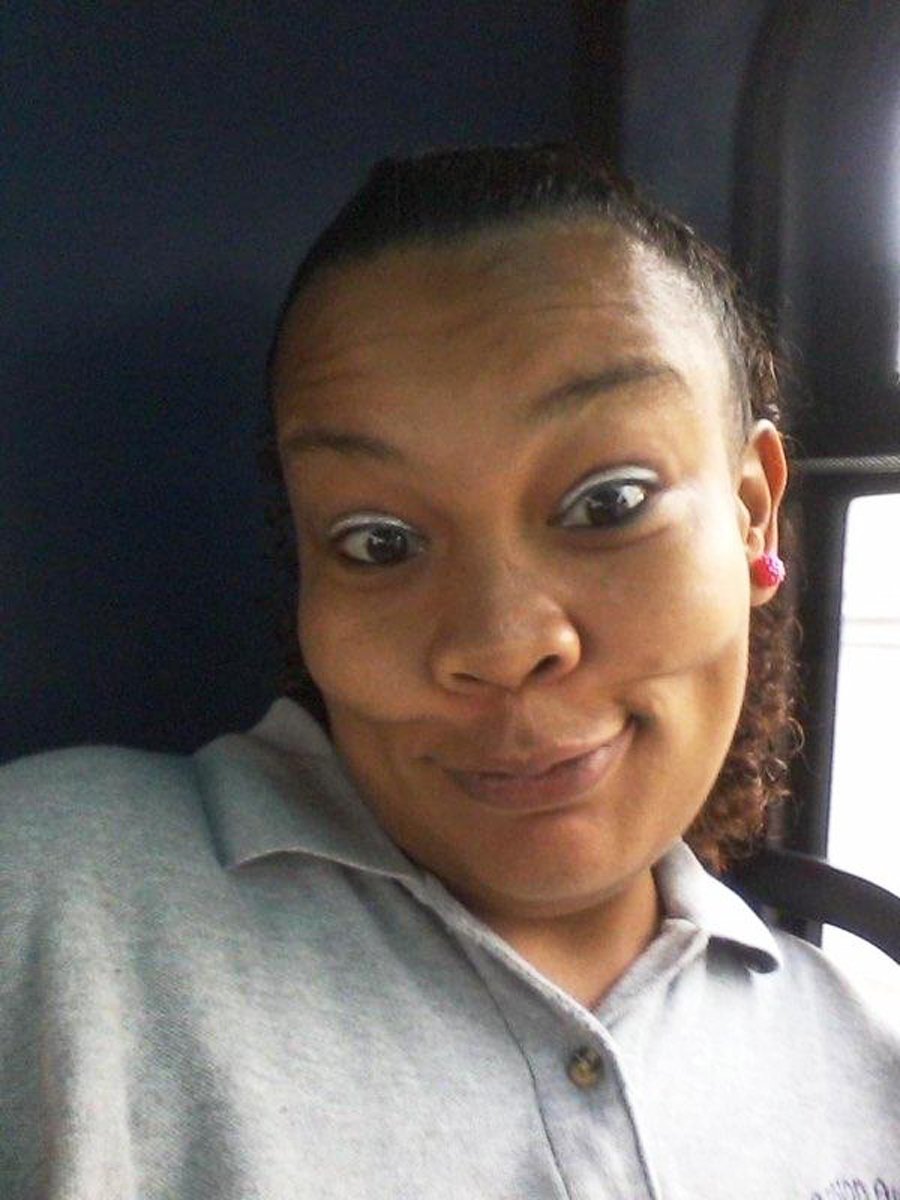

For months, Michelle Caddell had complained to Tulsa County jail officials of nonstop vaginal bleeding, discharge and pain.

It wasn't until she was bleeding through a menstrual pad every 20 minutes—and passing tissue from her vagina—that she was transported to an Oklahoma hospital to be screened for the cervical cancer that killed her at the age of 36, alleges a federal lawsuit filed on her behalf.

"There were nights where she would call and she would, you know, be weak," Cameron Lucas, Caddell's 20-year-old son, said of the roughly 10 months his mother spent in jail on a charge dismissed after she died in 2020. "She would bleed out...and they wouldn't send her to the hospital. They'd just send her back to the cell."

Her family's case is one of 160—30 involving inmate deaths—filed since 2015 against Turn Key Health Clinics, LLC, the private Oklahoma City-based medical provider at the jail where Caddell was detained, according to a Newsweek analysis of court records. Forty lawsuits remain active; Turn Key has won judgments in some and settled others, and two-thirds were dismissed—for reasons ranging from lack of merit to the legal failings of inmates representing themselves from jail, unaware of the complexities of the legal system.

The cases came to light in a Newsweek investigation into private medical companies such as Turn Key that have proliferated across U.S. jails and prisons since the 1980s. The cases highlight questions over how well such providers balance the healthcare needs of inmates against the bottom lines of their businesses—estimated by some to total $4 billion a year for jail contracts alone. About 60 percent of county jails rely on private medical vendors, according to the New York-based anti-incarceration advocacy group Worth Rises.

Newsweek began looking into Turn Key after breaking news in January of the 2021 death of 51-year-old Larry Eugene Price, Jr., in an Arkansas county jail. Price was found starved, emaciated and covered in filth, according to an ongoing federal lawsuit against Turn Key, doctors and nurses in its employ, and also Sebastian County, where he was found unconscious in his solitary cell.

Turn Key Chief Administrative Officer Danny Honeycutt declined to comment directly on any lawsuit against the company, which serves 100 facilities in 10 states. But he told Newsweek: "We live in a very litigious environment." While 160 lawsuits over eight years may seem a lot, Honeycutt said, "if that's the barometer for assigning competency, you're going to see that Turn Key leads the nation in this industry."

Turn Key, a regional company, is a relatively small player in a field dominated nationally by large companies such as Miami-based Armor Health, and Wellpath and YesCare—both based in Tennessee.

Among the lawsuits against Turn Key where inmates died, 11 were dismissed. The company won judgments in three, settled in three for undisclosed amounts, and 13 remain open. Of the 160 overall, many were dismissed on the merits, on technicalities or for raising frivolous arguments. But others were dismissed for reasons ranging from the inability to pay court fees to failing to meet court deadlines via mail, lacking expertise in structuring a legal argument or abiding by court procedure.

"It's not surprising to me that a lot of these cases get dismissed on technicalities because it's really challenging to navigate all those technicalities when you're fighting for yourself with no support while confined," said Emily Galvin Almanza, a co-founder of Partners for Justice, a New York-based nonprofit that supports public defenders and people facing criminal charges.

Much of the litigation against Turn Key—which started as a medical staffing agency before turning to a provider for jails—has been critical of its staffing levels. Many jails have a doctor visit only once a week—sometimes for as little as two hours, according to contracts seen by Newsweek and to lawsuits. Specialists offering dental care or cancer screenings visit even more infrequently. Some lawsuits allege people waited—their conditions worsening—for weeks or months.

"Doctors that are employed with Turn Key ... they're ultimately responsible for dozens and dozens of facilities across the state, sometimes even out of state," said Daniel Smolen, an Oklahoma-based attorney who has brought many lawsuits against Turn Key and other medical companies servicing correctional facilities. Smolen said often it was too late for patients by the time doctors arrived. "It's a huge problem," he said.

Officials with Turn Key denied that patients receive subpar care, noting that staffing levels are dictated by contracts with the counties they serve. Honeycutt said in at least two instances, Turn Key had asked for additional staff or money to provide proper care.

"In cases where we did not have the support of the county to provide adequate care, we have voluntarily ended our contract or fought to receive the support we needed," Honeycutt said.

Many of the lawsuits involve pretrial detainees like Caddell and Price.

Powerful State Lawmaker at the Helm

Turn Key was co-founded in 2009 by Jon Echols, an Oklahoma state politician who is also the company's president. The Republican, first elected in 2012, is the House majority leader, and sits on the House Appropriations and House Rules committees, among others, in the Oklahoma Legislature.

In an email to Newsweek, Echols said there was no conflict of interest between his public position and running a private company at the county level: "Oklahoma law recognizes that its part-time legislators have independent professions, and mine are properly documented and disclosed. I refrain from any votes that could affect my business interests, and I don't do business with the state of Oklahoma."

For his political seat, Echols earns $47,500 a year, plus $12,364 annually for his leadership position, according to his legislative aide Kaye Beach. His salary for Turn Key, like other financials of the company, were not disclosed to Newsweek and are not made public.

Turn Key provides care for a daily average of 25,000 people. The company's website says it delivers health care in jails "while controlling the program's financial burdens" to the community. It has a staff of 800 part- and full-time employees, but the company declined requests to provide a breakdown of doctors and nurses. But ZoomInfo, a company database firm, shows that a sliver of them are full-time employees with many working part-time or gig work. ZoomInfo also gives Turn Key's yearly revenue at under $5 million.

The bulk of the litigation against Turn Key has been filed in Arkansas (80 cases) and Oklahoma (71), with several other cases in Texas, Colorado, and Montana.

'Market Discipline Doesn't Exist in Prisons and Jails'

Turn Key typically gets a monthly payment to provide medical care. In at least one contract, it agreed to pay the first $500,000 of all off-site medical treatment before the county kicked in.

Critics say this creates an incentive to cut costs by not sending sick people to the hospital.

"The fundamental problem with private health care in prisons and jails is that the usual mechanisms of market discipline that we count on in the rest of the world—the idea that if a company gives bad service, if it injures or kills people, it'll eventually lose customers and go out of business—that market discipline doesn't exist in prison or jails," said David Fathi, head of the National Prison Project of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

However, a recent Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals opinion in the case Lucas vs. Turn Key Health Clinics noted that "to the extent it reveals a financial incentive, it is no more troublesome than any institution's general desire to maintain low costs to the extent reasonably possible."

Of the $500,000 up-front cost, Honeycutt said: "It is a cost-sharing agreement, and it is not a profit center for Turn Key. The amounts are based on the client's projected budget for this type of care, and it has the effect of normalizing monthly care expenditures for the counties we serve."

Correctional facilities are constitutionally mandated to take care of prisoners' healthcare needs under a 1976 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that deliberate indifference to an inmate's medical and mental health needs amounts to cruel and unusual punishment.

Industry leaders say that constitutional obligation is more important than profits—and that respecting it is good business given that it avoids hefty legal settlements.

"You're gonna have a much bigger cost by not providing a constitutional level of care," said Richard Forbus, vice president of program development for the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, an industry group that accredits jails that meet its strict standards.

Accreditation is voluntary, however. In Oklahoma, only the Tulsa County jail is accredited. In Arkansas, only one jail in all of the state's 75 counties is accredited. The Sebastian County Adult Detention Center, where Price starved, is not.

Though questionable deaths arise in state and federal prisons, advocates say that county jails tend to have more inconsistent health care than prisons. Jails are typically paid for by county governments, as well as via fines and charges to the inmates for goods or making calls, sending email and so on. Prisons often get federal and state funding, meaning less acute financial pressures. Unlike jails, prisons have less transitory populations and typically have full-time medical staff and facilities.

"It's not like the (inmate) can say, 'Wow, the health care at this prison is really terrible. I'm going to go down the road to this other prison and see if the healthcare is better there,'" Fathi said. "And so these companies can do a terrible job."

Honeycutt disputed that.

"We're here to provide healthcare, and to assume that we would cut corners or that we would not provide a service that is needed would be to impugn the integrity of the medical professionals who are there to help," he said.

"During COVID, finding any qualified nursing staff was a challenge. But if you look at our staffing levels, they are right in line with the conditions of contracts," Honeycutt added. "Every preventable death is a tragedy, and every negative outcome is a concern."

'They Completely Failed Her'

In Caddell's case, court documents state that Gary Myers, a Turn Key doctor at the Tulsa jail, wrote that her sick calls "do not fulfill medical logic," and refused her ibuprofen because he said she was abusing the system for requesting medical care.

"They completely failed her," said Yolanda Lucas, an aunt to one of Caddell's children. "She was in excruciating pain for months, with no treatment. And it wasn't until they realized that there was something terribly wrong with her that they released her."

The lawsuit, filed in the Northern District of Oklahoma, alleges Caddell was released without having to pay her $50,000 bond so that the county could avoid paying for her medical costs. No official reason was given in public records.

Turn Key denied in court filings that company staff violated Caddell's rights, also saying the family's lawsuit fails to mention two occasions that medical personnel provided medication, and that a pelvic exam was performed on Aug. 15, 2019.

A lower court determined that a doctor had not violated her civil rights—but an appeals court ruled that a negligence suit against Turn Key could move ahead, saying the district court erred in deciding at this stage that the company was protected by a law shielding state government entities and employees from negligence claims.

The appellate court ruled that providing some treatment is not a protection from liability if that treatment is inadequate, writing: "Treatment with Tylenol and accusing Ms. Caddell of fabrication was not only woefully inadequate but also plainly inconsistent with the symptoms presented. More to the point, Dr. Myers entirely failed to monitor her afterwards to determine if his treatment plan, if it can even be described as such, was working."

Newsweek was unable to reach Myers for comment.

Caddell was arrested as a passenger in a stolen car —her family says she didn't know it was stolen—and booked into custody on Dec. 27, 2018. The first official record of her requests for treatment was about six months into her detention, according to the complaint. In July 2019, she also sought help for pain in her hip and left thigh, according to the federal lawsuit.

In the three months that followed, she made multiple similar complaints. Caddell's tests showed an elevated white blood cell count and e. Coli growing from a specimen taken from her body—both symptoms of a more serious condition, but she was not sent to see a specialist for outside screening.

On September 27, a doctor gave the opinion that Caddell had cervical cancer based on a physical examination. Caddell tested positive on Oct. 30 for late-stage cervical cancer and extensive necrosis (tissue death) in her uterus. On Nov. 5, 2019, she was released.

She immediately began cancer treatment, but soon moved into hospice care, dying nine months after her release.

Caddell's family alleges she would be alive if her care hadn't been delayed for the months she spent in custody. In addition to Turn Key, the family sued Tulsa County, its sheriff and the medical staff responsible for her care in the jail. Claims against the county and the sheriff's office, which runs the jail, were dismissed and not appealed.

"I think my mom's death is in the hands of everyone" at the jail, Cameron Lucas told Newsweek.

Like Price, Caddell had not had her final day in court. According to a March 2023 Prison Policy Institute study, some 85 percent of inmates, or 427,000 out of the 514,000 people in America's county jails at the end of 2021, had not been convicted. Like Price, some 64 percent of jail inmates also suffer mental health problems, according to the American Psychological Association. All too often, it is untreated.

Price, whose IQ was below 55 and who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, had lost more than half his body weight in jail by the time he died, according to his estate's lawsuit in the Western District of Arkansas. Charged for threatening behavior after using his hand like a gun, he couldn't afford his $100 bail. By the time he died, he had resorted to eating his feces, according to the lawsuit. Turn Key's attorney in the Price case—Allie Ah Loy – has denied the allegations and said the company was not the medical provider during all of Price's incarceration in Sebastian County.

An Insider's Perspective: 'This Guy Needs to Go to the Emergency Room.'

Healthcare for the incarcerated is a growing business. A report by the Health and Human Rights Journal from last June put the business valuation for private prison and jail health care at $9.3 billion. The latest deal for Turn Key, which only serves jails, had a valuation of about $11 million, according to PitchBook, a market research firm.

A former Turn Key employee with extensive nursing experience who spoke to Newsweek on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution said medical staff felt the cost pressures at the Oklahoma facility where they worked. The former employee said they routinely had to go over the Turn Key doctor's head to get patients off-site care.

"I would call the physician, like, 'I really feel like this guy needs to go to the emergency room.' They would be like 'No,' and wouldn't listen to me," said the former employee. "Then I would just go above their head and be like ... 'I'm setting eyes on this person. I'm telling you, from my viewpoint, this guy needs to go to the emergency room, or this girl needs to go to the emergency room.' And then that's when they'd be like, 'Well, that's what you feel like needs to be done. Let's do it.'"

Turn Key said its medical workers make decisions based on the best and most appropriate care possible for patients.

The former employee also said that staff often reported to someone with the same medical credentials instead of someone more senior, which would be a violation of most states' laws. This allegation was made in several lawsuits against Turn Key. Honeycutt denied this.

Estelle v. Gamble

Estelle v. Gamble was a critical U.S. Supreme Court decision that established a jailer's deliberate indifference to the serious medical needs of a person in custody constitutes cruel and unusual punishment—and is a violation of the Eighth Amendment.

The case, decided on November 30, 1976, was the first to determine what it takes for someone in a jail or prison to successfully argue a violation of their constitutional rights under the Eighth Amendment, which guarantees protection from unreasonable bail and cruel or unusual punishment.

In other words: plaintiffs must prove their jailers inflicted sufficient harm so as to be considered deliberate indifference to serious medical needs.

While the plaintiff in Estelle v. Gamble—a prisoner who brought the case on his own behalf—didn't ultimately win his fight against a Texas prison, the case is important because it's the primary legal tool available to people in jails and prisons who believe their mental and physical health needs are being ignored.

According to Billy McKelvey, a former jail administrator and head of jail investigations at the Tulsa County jail, sheriffs across the United States have two choices: run medical care themselves or outsource it. In-house care means the jail knows what it pays for, including when inmates need hospital care. The failure with outsourcing, he says, happens when sheriffs turn a blind eye to the operator's practices.

"If you contract with a medical provider and you're paying them $350,000 a month, that medical provider wants to pocket as much of that $350,000 a month as they possibly can," McKelvey said. "You don't know what the true bottom line cost is...Why can't these medical providers get it?...Why are the medical providers allowing it to happen? It's a bottom-line number—how much money can they put in their pocket."

Critics like McKelvey say sheriffs sometimes try to offload their legal obligation of care onto private providers.

The Tulsa County jail contract with Turn Key, for example, had this provision: "The Sheriff of Tulsa County is not a physician licensed within the State to provide medical care and treatment to others; accordingly, the purpose of this Contract is to discharge the sheriffs duty to provide the required medical care by contracting with Contractor."

Tulsa County Sheriff Vic Regalado's office said the contract actually reflects how seriously the office takes the responsibility of caring for the health of people within the jail. The office also said they've had fewer lawsuits arising from the jail since contracting with Turn Key.

'These Lawsuits Are the Cost of Doing Business'

Most inmates in America—the most incarcerated nation in the world with about 2 million behind bars—are considered indigent, according to the American Psychological Association.

That also puts them at a disadvantage when it comes to challenging subpar medical care in court—if they even know they have the right to do so, said Almanza, previously a public defender in California and New York.

"Almost always, in order to bring a case in court, you have to exhaust the remedies inside the jail or prison first," she added. "That means knowing what the right form to file is when you've been injured and knowing how to fill it out properly. And knowing what the process is thereafter."

Brice Timmons, a Memphis attorney who has sued Turn Key, said that private medical providers know it's hard for desperately poor inmates or their families to win a lawsuit against them—whether from inside or out.

"These lawsuits are the cost of doing business for companies," he told Newsweek. "The ability of these individuals or the families to continue dealing with protracted litigation diminishes every day."

He said that means people will often have to accept settlements for "pennies on the dollar."

Less than 4 percent of the litigation against Turn Key has resulted in settlements. Some of the cases have yielded big payouts by the counties running the jails, but the portion of the settlement paid by Turn Key, if any, has not been disclosed.

In the case of Anthony Huff, settled in 2019, the Garfield County Board of Commissioners in Oklahoma paid $12.5 million; Turn Key's settlement was not revealed. Huff was arrested in 2016 for public intoxication. He died at the Garfield County Detention Center after allegedly being denied medical care for hallucinations. He stopped breathing after more than two days bound in a restraint chair, according to a lawsuit filed on his behalf.

In the case of Ronald Garland, who was arrested for DUI in 2017, the Creek County sheriff and other individuals named in the lawsuit paid $750,000. Turn Key paid an undisclosed amount. Garland was allegedly not provided medical treatment for toxic levels of intoxication. The lawsuit alleged Garland was beaten and restrained in a chair with his head bent to almost touching the floor. He died of oxygen deprivation to the brain.

Since the lawsuit over Price's death was filed Jan. 13, two others have been filed alleging wrongful death: The family of Eusebio Castillo Rodriguez, 42, sued Turn Key and the county, alleging he died after untreated alcohol withdrawal at the Union County Detention Center in Arkansas. And the family of Steve Standridge sued Turn Key and others in March over his death in the Faulkner County Detention Center, also in Arkansas. Standridge, whose leg had swollen up massively in jail after a suspected spider bite, died of sepsis shortly after being taken to hospital.

Neither the Faulkner County jail nor the Union County jail is accredited by the NCCHC, Forbus said. The sheriff's office in Union County did not immediately respond to a request for comment. Faulkner County referred Newsweek to the Association of Arkansas Counties, which declined to comment on open litigation.

'A Pretty Scary Prospect'

Another lawsuit facing Turn Key is that of Nandre Ervin, a U.S Marine veteran who served in Iraq and needed prescription eye drops for his uveitis—inflammation of the eye's middle layer—and who had been receiving free drops from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Ervin, then 49, was arrested March 15, 2020, on an assault charge and held at the Pulaski County, Arkansas, jail. Despite swelling that forced his right eye to shut, the complaint alleges that instead of the eye drops, he was sometimes given only "sterilized purified water ophthalmic solution," or eye wash, to keep down costs. His suit says that during four days of excruciating pain, he was not examined physically by any nurse.

Covid hit hard at that time, and any communication with nurses or a doctor happened over videoconference.

"No one ever was able to see me in person, see my eyeball up close and tell me what was wrong," Ervin told Newsweek. "I would tell them on video, but they would just ... tell me, 'Go back to your cell.'"

After more than two weeks being locked up and complaining of dizziness, eye pain and blindness, a pounding headache and stomach aches, the suit says he was told by medical staff he likely suffered dehydration and to drink water and eat ice chips to rehydrate.

On March 31, 2020, the complaint says "he was sent out to a hospital with the paperwork listing his condition as vulvitis—an inflammation of the vulva," according to the federal complaint.

His lawyer, Timmons, was scathing. "I mean, a nurse that can't tell the difference between the inflammation of the eye and the inflammation of the female vulva is a pretty scary prospect to have as your caretaker."

The Pulaski County Sheriff's Department didn't immediately respond to a request for comment.

Ervin said much of the vision in his right eye remains blocked despite surgery.

' I Yelled for Them to Declare a Hospital Emergency'

James "Doug" Buchanan left jail a quadriplegic.

Incarcerated in Muskogee County, Oklahoma, Buchanan said first his left arm stopped working. Then his right. Then his legs. Other inmates had to drag him along a tile and concrete floor so Buchanan, now 61, could eat, use the phone or urinate, according to his federal lawsuit, currently on appeal.

Buchanan's suit contends that his cries for help were ignored for almost 11 days; a lower court dismissed his claims, ruling he was seen by jail staff once a day and got help once "jail staff believed emergent care was necessary." But Buchanan's lawyer is arguing in an appeal currently before the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals that the lower court ignored evidence favorable to his client.

At the time he entered custody, Buchanan did not know that his neck had been fractured in an accident weeks before that also broke his ribs and collapsed a lung—or that an infection of his spine was spreading through his body, rendering his extremities useless.

"I honestly felt like I was gonna die," Buchanan told Newsweek. "Thinking about it just makes me wanna cry."

Buchanan's civil rights lawsuit was originally filed in May 2018 against the county, his jailers and Turn Key. A federal district court dismissed the lawsuit against Turn Key, saying the complaint lacked an "underlying constitutional violation," and found Turn Key was immune from a negligence claim under state law. His appeal, filed in September of last year, names Turn Key, the Muskogee County sheriff and the county as a whole.

Jailed initially on a larceny charge, Buchanan said he is now permanently disabled because his condition was not diagnosed or treated when he was in custody, despite being seen by at least two nurses. His appeal claims the lower court ignored evidence such as multiple inmates testifying to Buchanan's rapid decline over several days, with allegedly inadequate intervention by either Turn Key or jail staff. He was sent to the ER after a Turn Key nurse, who had noted his worsening pain and inability to use his lower extremities earlier in the day—and scheduled him to see a doctor during rounds the following week—found him soaked in his own urine.

Buchanan says his troubles began in August 2016 after he picked up a suitcase he had swerved to miss on the road. While he says he planned to drop off the suitcase containing girls' clothing for donation the next day, he was charged with larceny.

He was bonded out of jail, but could no longer use his car. His luck got even worse. He was hit by a car while riding his bike. As the pain persisted, he could no longer work and he lost his temp job. The larceny charge was still hanging over him and, unable to pay, his bondsman dropped him. It was back to jail.

At intake, according to Buchanan and his federal complaint, he informed jail staff and Turn Key personnel of the injuries he knew about. In the medical questionnaire, he wrote that he had "broken ribs, collapsed lung, burnt fingers, neck problems."

"On the very first day I asked to see a doctor, something was wrong," he said.

"I made it to about day 11 and had come to the conclusion I was going to die. I told the other inmates to scatter but be in yelling distance. I urinated all over myself...And I yelled for them to declare a hospital emergency."

Finally he was taken to hospital. With the closest trauma center full and a nearby community hospital unequipped to help, Buchanan was helicoptered to Hillcrest Hospital in Tulsa, 50 miles away. "I woke up at Hillcrest to a guy at the foot of my bed, which was a brain and spine surgeon telling me I had a broken neck, was paralyzed from the neck down and would not be able to walk or use my arms ever again."

The doctor from Hillcrest, Clinton Baird, gave his view of the jail's failure to send Buchanan for proper care in a deposition for the lawsuit, noting that his condition could have been treated—and disability prevented—with some antibiotics.

"This whole thing is a grossly negligent delay in diagnosis...an untrained human being with no medical background could say, 'hey, that guy, something's wrong with him'," according to Baird's deposition. To not have had the healthcare team do a further evaluation or send him to the hospital, Baird said "is grossly wrong."

Buchanan sits at home most of the time now, as he has for six years. He says he can't work, he can't drive and his main hope is to get redress from the court.

"I don't know what else to say," he said. "I'm 100% disabled."

Buchanan counts himself lucky he didn't die. And through rehab, he has regained some ability to walk—he first used a wheelchair, then a walker, and now has to lean on things to get around. But he said the nerve damage throughout his body is likely permanent.

Although help came too late for Caddell, her family hopes that she will be remembered as a fun-loving prankster, the loudest mom at her kids' sports games—and the mom who managed to make a tough Christmas extra special, even on a shoe-string budget.

"I think that my Mom would understand why we're doing the lawsuit," said Cameron Lucas. He was sure that she would have done the same to get justice for anyone else: "And to get to prove that what we're fighting for is right."

Valerie Bauman can be reached at v.bauman@newsweek.com. Find her on Twitter @valeriereports

Eric Ferkenhoff can be reached at e.ferkenhoff@newsweek.com. Find him on Twitter @EricFerk

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.