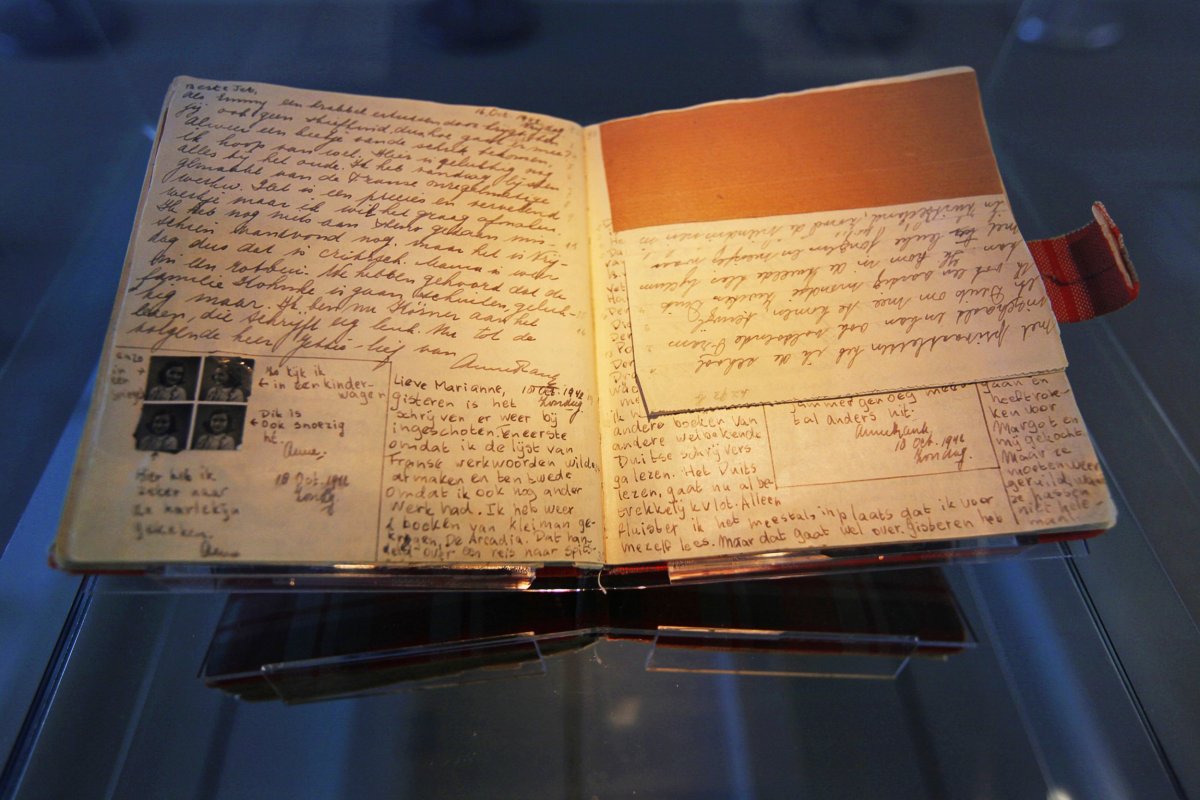

Jacqueline van Maarsen will never forget the sight of Anne Frank's shoes, left on the floor in front of her bed. The Franks had vanished, and the normally tidy home was in disarray. Van Maarsen, Anne's best friend, was accompanying another girl into the apartment to fetch a kitchen item that had been lent to the Franks, she recalls. Anne and Jacque had promised to leave one another a note, should either of them need to disappear, but such a message was nowhere to be found. Nor could they locate the red and beige plaid diary with a clasp on the side that Anne had received for her 13th birthday just a few weeks prior.

Van Maarsen couldn't have known then that the diary was in an attic across the city's streets and over its web of canals, and was to be Anne's companion for the next two years in what she called "the Secret Annex." She couldn't have guessed that it would eventually be read by millions of strangers or that more than seven decades later she would be speaking about the Holocaust as the childhood friend of one of its most famous victims.

On a Friday afternoon at the end of May, an 86-year-old van Maarsen spoke about her friend, and about why it is she travels around the world to do so as an octogenarian. She and her husband Ruud Sanders had arrived in New York City that week to attend the Champions of Jewish Values International Awards Gala, where van Maarsen received the Champion of the Human Spirit Award "for her dedication to promoting Jewish values and keeping the memory of Anne Frank alive."

Van Maarsen settled into a spot on a small sofa in the corner of the Hotel Elysee's upstairs lounge, with her husband seated beside her. A yellow-tinged light filled the room above wooden furniture and a maroon carpet with gold patterns, contrasting with the bright daylight filtering through the windows overlooking Manhattan's East Side. Van Maarsen is slight, with a short crop of hair and glasses that seem to float unframed on the bridge of her nose.

Born in Amsterdam after her parents moved there from Paris, van Maarsen remembers at a certain point German children began to appear in her class. She was too young at the time to understand that many of them were Jews emigrating out of Germany after Hitler and the Nazis' rise to power. "I had a little friend who was my age and she came from Germany," she says. "My father told her father, 'It's good that you came here because you're safe.' So I was puzzled; I was only 5 years old and asked the girl, 'Why were you not safe in Germany?' I was quite astonished. And she said the word 'anti-Semitism,' which I didn't understand at all."

Though she didn't know them yet, the Franks were one such family who fled Germany in the early 1930s, soon after Hitler was named chancellor on January 30, 1933. "Because we're Jewish, my father immigrated to Holland in 1933," Anne wrote in one of her first diary entries. In another entry, written just two days after she received the diary, she wrote, "I only met Jacqueline van Maarsen when I started at the Jewish Lyceum, and now she's my best friend."

The restrictions on Jews began piling on after the German invasion of the Netherlands in May 1940. As Anne describes in her diary entry from June 20, 1942, "our freedom was severely restricted by a series of anti-Jewish decrees." Jews were to wear a yellow star and children could attend only Jewish schools. They were prohibited from using streetcars and cars, going to the theater or movies, using swimming pools and athletic fields and visiting Christians in their homes. Anne wrote, "Jacque always said to me, 'I don't dare do anything anymore, 'cause I'm afraid it's not allowed."

But Anne's attitude was, "We can't go to the cinema, so we make a cinema ourselves," van Maarsen recalls. The girls would cut out pictures of film stars and sort the postcards they collected. They played monopoly and chatted about all sorts of things; Anne especially liked talking about their classmates, van Maarsen says. Once, Anne declared that they should exchange help learning German and arithmetic, though nothing much came of it.

As van Maarsen recalls, Anne was the more boisterous of the two, and unlike her introverted best friend, always wanted to be surrounded by people. "I said, 'We are so different, how is it possible that we are such good friends.' And she said, 'That's just the thing why we are good friends,'" van Maarsen recalls.

Anne was one of the first classmates to disappear, before the situation became dire. Her parents, Otto and Edith Frank, had already been making arrangements to go into hiding, but a call-up notice for her sister Margot from the SS hastened their departure by several days. Their partners in hiding, the van Pels family (called the van Daans in Anne's diary), also arrived earlier than planned, as "the Germans were sending out call-up notices right and left and causing a lot of unrest."

Van Maarsen found herself in a unique situation among her classmates at the Jewish Lyceum. Her father came from an observant Jewish family, but he was not as religious, and married a Roman Catholic woman, van Maarsen and Sanders explained at the Hotel Elysee. At first, her mother became Jewish for the purposes of the congregation in Amsterdam, and when the Nazis arrived, the family was entered into their list of Jews. But as it became increasingly clear just how grim the future was for Jews in occupied Holland, van Maarsen's mother managed a feat that would save all of their lives. She convinced the German authorities that she wasn't Jewish (which was true) and was able to get the names of her husband and daughters off the list as well.

"I never knew how it exactly went," van Maarsen says, though she recently found out her mother may have spoken to Hans Calmeyer, a German lawyer who headed the interior administration office in occupied Holland that dealt with cases of doubtful ancestry. Calmeyer is said to have saved a few thousand people by approving applications unusually often, even when documentation was clearly fictitious. She says she writes about this revelation in her most recent book, Your Best Friend, Anne Frank, which is published in Dutch and German.

"I had two lives during the war," says van Maarsen, who went from wearing a yellow star and attending the Jewish Lyceum to being a non-Jew in the eyes of the Nazis before they could be called up and sent to the camps. "It was very weird and I felt awful, and after that," she recalls, "I went to a non-Jewish school and nobody talked about the Jews and I didn't tell the people what had happened to my family."

After the war, Otto Frank appeared at the van Maarsens' door. Van Maarsen had been certain Anne and her family were in Switzerland, based on a rumor the Franks themselves had started before going into hiding to cover their tracks. Otto knew already that his wife had perished at Auschwitz, van Maarsen recalls, and soon found out that his two daughters, Anne and Margot, had died at Bergen-Belsen.

"He was very sad and wanted to talk to me all the time about Anne. And I didn't like that. I didn't want to remember these bad times, it was so sad," says van Maarsen, who was just 16 at the time. "He was crying quite a lot. It was very difficult for me," she adds. She was finally able to read the promised but never sent goodbye letter that Anne had written to her and copied into her diary. After Otto learned of Anne's death, he began reading her diary, which two of their helpers in hiding, Miep Gies and Bep Voskuijl, had gathered and put in a drawer after Anne and the others were arrested on August 4, 1944.

"I was astonished that he—at a certain moment I don't know—he wanted to publish the diary. And I thought, 'Who can be interested in this writings of a young girl and about the war,' nobody wanted to think about the war anymore," van Maarsen says. "But I wrote a letter to him and I said maybe Anne's diary will one day be famous, which I didn't think, but I just wrote it for him to be friendly."

Indeed, on June 25, 1947—just over 68 years ago and a couple weeks after what would have been Anne's 18th birthday—the first version of Anne Frank's diary was published in Dutch. Translations in German and French followed in 1950, and an English translation was published in the United States in 1952, with a preface by Eleanor Roosevelt. The diary has been translated into 70 languages and sold more than 30 million copies.

For many years, van Maarsen preferred the anonymity of the pseudonym Anne had assigned her in the diary, Jopie. "I didn't want to talk about it," she says. "I didn't want to lose my own identity, because people are interested in me because this friendship." She studied in Paris to become a designer bookbinder—a profession that allowed her to work alone in her workshop—and married Sanders, who she knew as a neighbor when she was a child.

She remained quiet about her identity as Anne's best friend, "but at a certain moment I felt...it was necessary because things happen around her [memory] that I didn't like," she says. "I had the idea that some people were taking too much profit off of her celebrity. So I started to write about it. I knew that it would start but I thought I have to do this because Anne would have been furious if she had known, that she would be misused."

For the last several years, she has been writing books, traveling to speak—particularly with students and young people—about Anne and the Holocaust, and giving interviews to the media. "I do it to show what can happen when racism and anti-Semitism is pushed too far and I hope it helps," she says. "I know that it has impact when I tell my story and it has all to do with Anne," she adds. "That's why people get interested." In other words, her friend Anne sparks interest all over the world and allows her to speak about the Holocaust, anti-Semitism and prejudice.

"People love Anne, I found out.… This little girl, the whole world knows her now, and I know she would have loved it," van Maarsen says. "Everything I do is in memory of Anne, because I'm not the kind of woman, and never was the kind of girl, that wanted to have attention," she adds, remembering the extrovert and introvert that became friends seven and a half decades ago. "We were so different, I know that Anne would have loved it, but I didn't like it."

Van Maarsen, her fluent English burdened slightly that Friday in May by fatigue from a busy schedule and lingering jetlag, explained that the frequent travel and list of commitments is worth it if she can reach a younger generation and help them grasp the often unfathomable events of the Holocaust.

Nowadays, that work often takes her to Germany. In the Netherlands, she says, the Jewish community is not particularly interested in Anne Frank. "They think, 'We have our story, it's the same story, why Anne Frank?'" she says. "And I try to tell them it's the diary that reaches people, and because of the diary I can talk about it. Because of Anne—everybody knows Anne—I can use her for my speeches."

"I always have a full house, not because I'm Jacqueline van Maarsen, but because of Anne. I know quite well Anne attracts people," she adds, and "it's very important I can talk about the Holocaust again and again."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Stav is a general assignment staff writer for Newsweek. She received the Newswomen's Club of New York's 2016 Martha Coman Front ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.