It's unsettling, even before you enter. Stenciled on the ground, just outside the entrance to the International Center of Photography's (ICP) new museum in Manhattan, are words informing visitors that once you enter, you "consent to being photographed, filmed and/or otherwise recorded" and "surrender the right to the use of such material throughout the universe in perpetuity."

The rather dramatic legalese appears on the wall inside the galleries as well, reminding you of the ubiquitous presence of cameras, even at home as you dance naked in your living room or eat dinner in front of your computer. These spaces are private, but if the new museum's inaugural exhibit, "Public, Private, Secret," teaches you anything, it's that nothing is as private as you think it is.

"When you go out into the outside world, look how many cameras there are," says ICP Executive Director Mark Lubell. "There are security cameras but also people taking pictures everywhere…. We're all part of this."

After closing the doors of its midtown museum last January, the ICP on June 23 opened its new space three miles south, at 250 Bowery. The change in location allows for a fresh take on a four-decade-old mission: to better understand the way images affect our lives.

That mission is clear from the moment you step into "Public, Private, Secret," which opened Thursday with the new museum. The first room is dimly lit, in stark contrast to the bright white "village square"-like entry area, almost like a negative. Warped mirrors wrap around you, reflecting a few scattered lights, which bounce off the smooth gray floor. Small alcoves on either side feature a total of four screens, each playing video works.

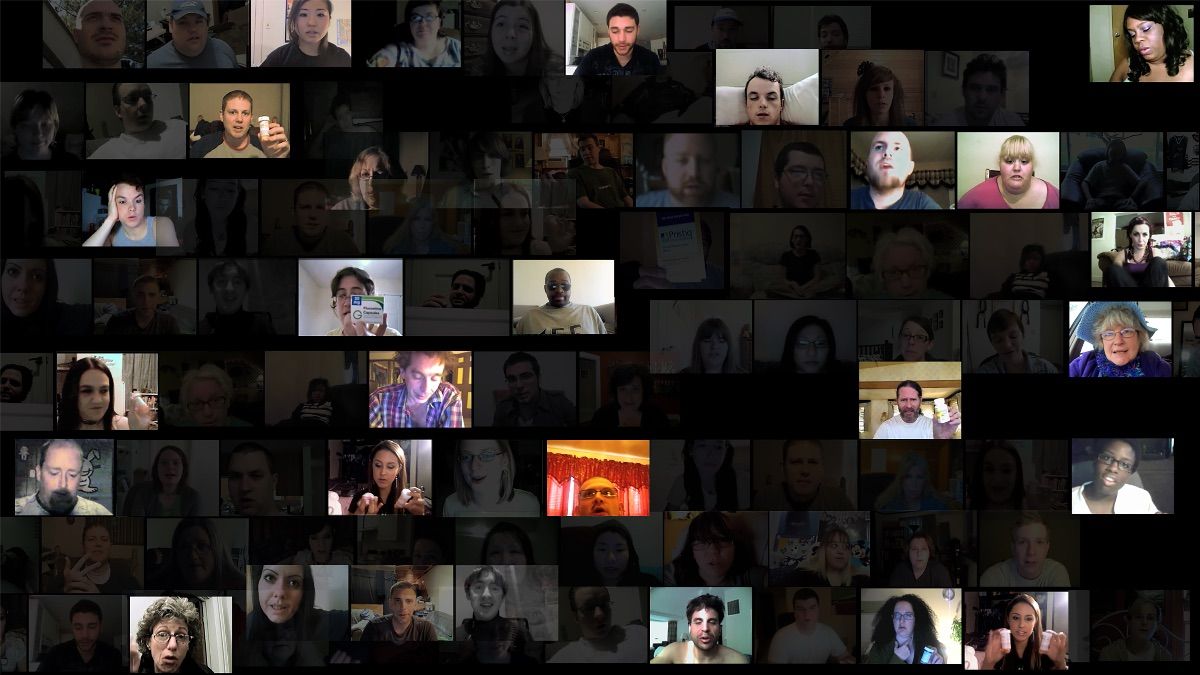

Natalie Bookchin's "Testament," for example, is a series of "collective self portraits" like "My Meds," "Laid Off" and "I Am Not," which orchestrate footage from hundreds of video diaries she found online. Rectangles of varying sizes appear on the large screen, one at a time or in rows or clusters, like a switchboard lighting up in random patterns. Each features a video of a stranger as his or her voice narrates. Sometimes the voices overlap, like a chorus of confessionals. "I could use your prayers to find another job," one says. "I love being gay," says another.

With Bookchin's pieces, curator Charlotte Cotton says, there's "this wonderful sense of people sharing a lot, but then also the kind of repetition suggesting very learned behavior how to represent your personal life online."

Another work caught early visitors off guard. It's located in a small hallway that connects the first gallery of videos to a larger one downstairs and may have sent many people home to place stickers over their webcams (a precaution even Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg appears to take).

Kurt Caviezel's "Pas de Deux" features a series of screen shots from a publicly accessible webcam arranged in a grid. A man moves and whirls to a projection of what looks like a dance performance. He's naked and everything is visible—his private rehearsal and his private parts, which this anonymous man doesn't know are now on display in a museum in Manhattan.

There are mirrors in the main gallery downstairs too. It's no mistake that visitors can literally see themselves throughout the exhibit. "You're in this," says Cotton. "You're implicated." The art on the walls tackles subjects ranging from celebrity to criminality and state surveillance to voyeurism, with a deliberate mix of pieces from contemporary artists and their predecessors.

Six square real-time screens scattered around the room, which are curated by Mark Ghuneim and students from ICP's New Media Narratives program, use algorithms and search terms to pull tweets and images related to themes like transformation, morality tales and privacy.

The first wall on the left, for example, begins with a paparazzi-style Cindy Sherman photograph, followed by a video that flips through the pages of Selfish, Kim Kardashian's 2015 book. Next to the selfie queen, there are three sets of Polaroids by Andy Warhol—suggesting the notion of 15 minutes of fame—pasted on smaller framed mirrors. That's followed by Marisa Olson's "The One That Got Away," a 2005 spoof video of American Idol, and a real-time stream of content from "creators" who became famous online and curate their presence for massive social media followings.

Other works around the room include mugshots from the 1920s; Mike Mandel and Chantal Zakari's archive of pictures taken by professional photographers and ordinary people during the manhunt following the Boston Marathon bombing; one photo from a series of portraits Yale Joel snapped through a two-way mirror for a 1946 Life magazine project; an image from Larry Sultan's "The Valley" series, which he captured on the set of an adult film in the San Fernando Valley; and copies of Transvestia magazine from the 1960s, featuring photos of subscribers on the covers.

The final gallery in the back has only one work: Phil Collins's 2009 "free fotolab," in which the artist (not the singer-songwriter of the same name) collected undeveloped rolls of film from willing participants. A carousel slide projector clicks and the room periodically goes dark between random snapshots of strangers' film rolls: a day at the beach, a dad and his baby daughter, two men at work on a snowy day. Collins's project, according to the wall text, "questions the relationships between exhibitionism and sharing, voyeurism and exploitation, and production and ownership," a fitting coda to the exhibit.

When you leave, the stenciled words on the ground are upside down, as though they are no longer relevant. Yet it's still hard to shake the thought that everyone can become the subject of other people's images, whether you're aware of it or not.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Stav is a general assignment staff writer for Newsweek. She received the Newswomen's Club of New York's 2016 Martha Coman Front ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.