Former Sex Pistols frontman John Lydon—aka Johnny Rotten—stomped into the galleries of the Museum of Arts and Design (MAD), in New York, in low-top Doc Martens, pleated black harem pants and a shirt of the same fabric but rendered in white. The entirety of this outfit was draped in an oversize black vest, its farthingale undone, suggesting a toned-down version of the bondage straps Vivienne Westwood once dressed the punk musician in onstage when he sang songs like "Anarchy in the UK" with Sid Vicious on bass.

Rotten was once again ready for the spotlight as a gaggle of media surrounded him.

"The first term I time I ever heard the word punk was in a Caroline Coon article. She called me the 'King of Punk,'" Rotten recalled, entering the show dedicated to the genre he helped establish. "And I found that really offensive—I'm no toy boy in Mr. Big's Prison!"

Punk is having a revival: Epix released an Iggy Pop-hosted miniseries about the subculture, the Museum of Sex has a show dedicated to punk's lust in leather, and even the Metropolitan Museum of Art is currently displaying guitars played by the likes of Patti Smith.

In the center of this counterculture constellation is MAD's new exhibition: "Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die: Punk Graphics, 1976-1986," which explores the visual language punk communicated during its most popular decade. Newsweek took a walk-through of the show with the counterculture icon.

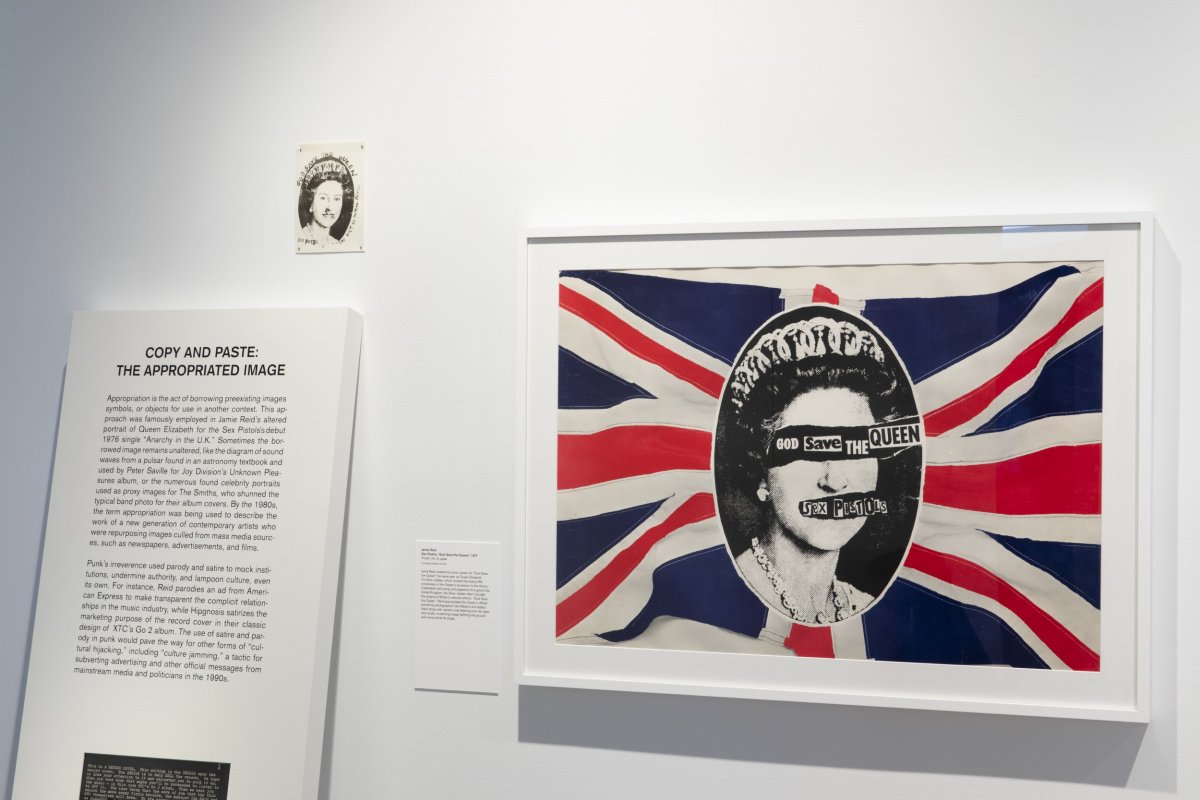

Rotten approached one of the hallmarks of the exhibition, an oversize print of Jamie Reid's cover of the Sex Pistols' single "God Save the Queen." In the image, Queen Elizabeth II's visage lies in the center of the Union Jack, the U.K. national flag, her eyes covered by black bars with collaged letters reminiscent of a ransom note, spelling out the single's name. The band's name appears in a similar style as a gag on her mouth. The image is a good summation of the rebellion and bricolage style that informs the entire exhibition and evoked pangs of nostalgia from Rotten.

"As a taxpayer, she's my property," he said, as he slapped the famous image of the monarch, flagrantly breaking the cardinal rule of museums to never touch the artwork. Of course, since it belongs to him, he has free reign. "She's missing the safety pin through her lip," Rotten noticed, only to see the version he just described tacked to the wall on the left.

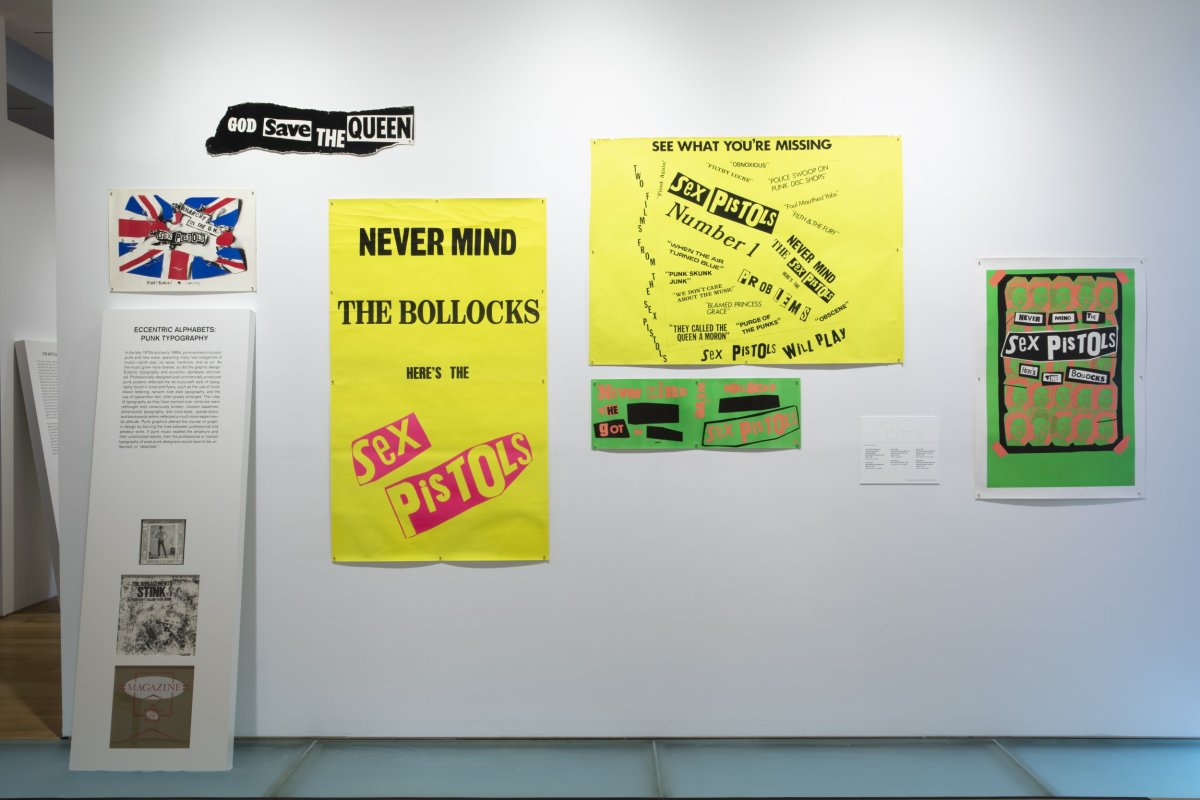

In addition to that royal riff, the MAD exhibit, the majority on loan by private collector Andrew Krivine, celebrates the spirit of punk in every dot of its halftones: consciously broken rules of typography, with words scrunched together, stretched out or written upside down; confrontational color palettes of shocking pink, acid green and piss yellow; and repetition of offensive imagery reminiscent of Andy Warhol's Car Crash and Race Riot series. For the show, Chris Scoates, MAD's Nanette L. Laitman director, gathered zines, pins, posters and album covers from greats like The Smiths, Blondie, New Order, The Clash, Buzzcocks and more.

Rotten, in typical Punk fashion, seemed disheartened by some of the work hanging on the wall because it seemed derivative of what the Sex Pistols had done first. Rotten observed a small, pixelated poster the band had created of themselves in off-tones of pink and green, and then noticed a larger poster promoting The Clash, depicting bassist Paul Simonon smashing his guitar rendered in a similar palette. "I've got some friends in that band, so it's very difficult for me to say this—not!" Rotten began to dig in the knife. "They're trying to use our colors, but they've gone off-shade. Wasn't their printer working?"

He moved on to another poster, a black-and-white grid of bugeyed punks. "These are stills of Pistol crowds and audience scenes," he said. "Interestingly enough, by the way, the Ramones used [this] in their documentary, because they didn't have any crowd scenes of their own." Newsweek asked why the Ramones didn't take their own footage. "Because there wasn't any crowd to take!" Rotten guffawed.

When asked if Rotten speaks anymore with any of his contemporaries, the images of whom he was surrounded by, he laughed. "Most of 'em are dead. But, no, I never really knew 'em. They always try to make out that it was some kind of great scene, that we all hung out together. It wasn't really like that at all."

Soon, Rotten sobered on what the display of these crude-yet-brilliant images really meant to him, and Punk as a whole. "I knew from the outset that we weren't going to be a band that let the label dictate the packaging," he said. "So the artwork was internal, and a great deal of me went into that."

Rotten has never let labels dictate who he is—or not told the truth however uncomfortable it is.

"I was born out of holy wedlock. I'm a bastard," he spits out. "And in them days for a Catholic woman—I mean, mum and dad married sometime after—but that was a terrible shame on them," he admits. "It's this shame that made these songs and this art so vitally important. I'm not just ranting and raving up there, I'm divulging some really, really hard truths about my life. And I won't have that lumped in with silly showbiz twats."

Inherent in punk is the political—but not necessarily how we might see it exercised these days. Rotten advocates temperance in terms of cultural and political activism, which may come as a surprise to those thinking the Pope of Punk would be as extreme as his stage persona. "It's like [the Sex Pistols song] 'Bodies,' about abortion," he said. "It's not totally for it or totally against it—it poses a question, and it deals brutally accurately with what abortion is: A screaming, bloody mess. And I have to think of myself in this respect—my mum could have easily had an abortion, and I wouldn't exist."

This authenticity speaks to why punk has survived the commodification and commercialization of itself, as well as the ever-changing nature of our culture. The brilliant DIY design on display, made in garages and roach-infested flats, manifests the spirit of Rotten's thesis: "Art should be part of the music, and challenge you, really."

This type of challenge is what Rotten feels in every regard: Punk should never be comfortable, even if people in small towns don Doc Martens and defy their parents. Even Donald Trump is not extreme for the musician.

"Some good might come out of this," Rotten pointed out about Trump's presidency. "I'm sick of all politicians. I've been saying it now all my life now," he complained. "They're rotten to the core, not to use my name in vain. And [Trump]'s a bad penny, but by God, he's having a stirring effect in there. So you know, don't knock it."

Is Donald Trump a punk, then? Is his antiestablishment attitude toward U.S. democracy a positive influence in that it gets people involved in politics? Rotten said, if the economy is really as good as Trump claimed, "what in the hell are you all complaining about?" But the King of Punk also understands that it may not be true, so he poses this question: "Is he a Sex Pistol? He may well be. He might not like that at all. I hope so. I hope it aggravates him to no end!"

All the slicing of paper with scissors and sniffing the glue used to commit those clippings to the work now hanging in the Museum of Arts and Design culminated into something bigger, Rotten mused: "We've got to work hard to make this world work properly."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.