A pea-sized capsule filled with radioactive caesium-137 that is lost in the Australian outback could be very dangerous if it isn't found, possibly giving nearby life cancer.

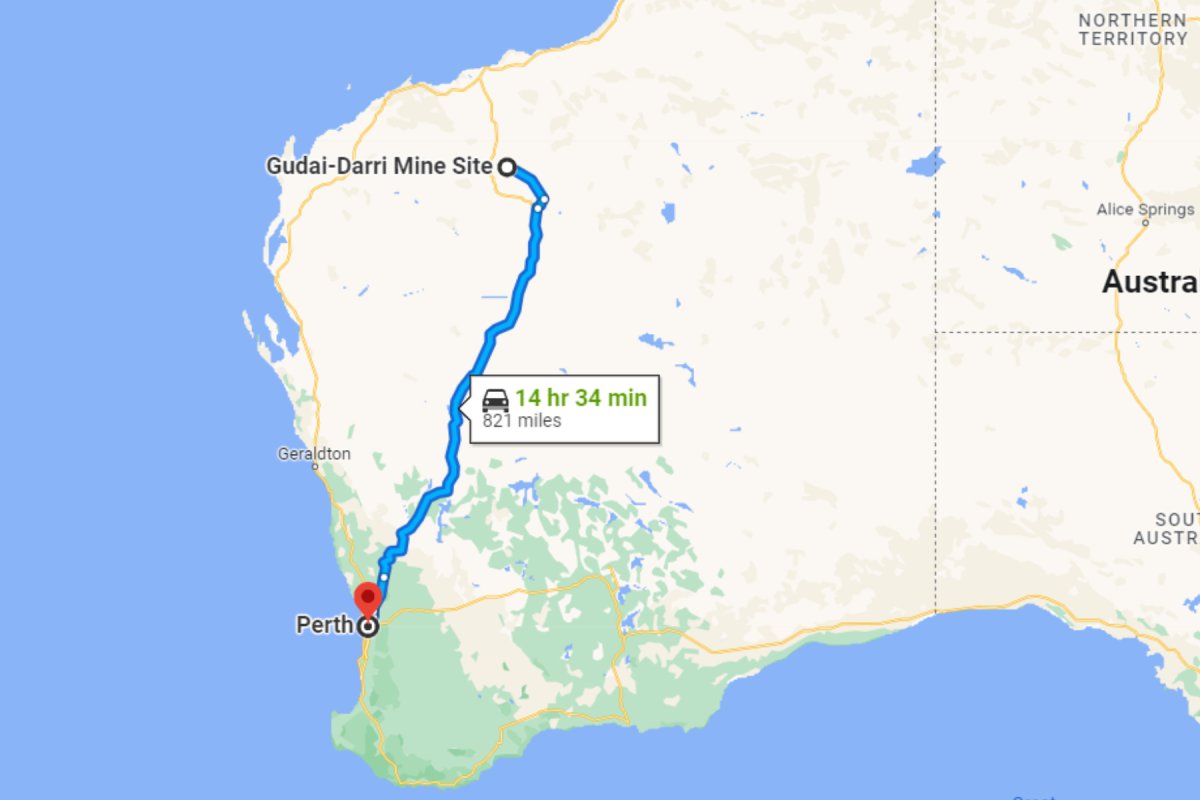

The tiny capsule was lost somewhere on an 870-mile stretch of road between mining company Rio Tinto's Gudai-Darri iron ore mine in the Pilbara region of Western Australia and Perth, a journey that a company vehicle made between January 12 and January 16. The capsule was only noticed missing on January 25.

If the capsule remains missing, it could pose dangers both by direct exposure to the gamma rays emitted by the radioactive material, as well as by contamination of the skin or ingestion of the material inside, if the container is ruptured, possibly leading to cancer.

"The dose from the gamma radiation coming out of it is between 1 and 2 mSv / hr [milliSieverts per hour] if you stand about 1 m[eter] away from it," Edward Obbard, a senior lecturer in nuclear engineering at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, told Newsweek.

"That is 1/20 of the annual allowable radiation dose for a radiation worker—so actually quite safe for any person who happens to walk by, or step over the source or even hang around for a while right next to it."

Over a long period of time, the capsule could cause cancer, but due to its likely location in the middle of nowhere, this is not too much of a risk, Obbard said. Australian health authorities have warned that standing within 3 feet of the capsule is the equivalent of receiving 10 chest X-rays in an hour.

"The risk of cancer from radiation is 5% per Sv. So if you (hypothetically!) camped right next to the source and stayed there, then every 20 hours, say every day, you would increase your risk of cancer by 1 in 1000. So after a couple of months doing this you would have a 1-in-10 chance you will get cancer. Probably too much to accept! But then who is going to do that?" Obbard said.

The half-life of the radioactive material inside the capsule, caesium-137, is around 30 years. This means that the level of radioactivity decreases by one half every 30 years, and therefore will only be half as dangerous once 30 years have passed.

"One concerning possibility is that somebody does find the source, but they do so in a couple of years from now, while it is still quite dangerous but everybody has forgotten the news and they don't recognise what it is," Obbard said.

If someone were to find it by chance and take it home, then they could be at increased risk.

"By far the most serious concern is contamination," Dale Bailey, a professor of medical imaging science in the faculty of medicine and health at the University of Sydney and Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, said in a statement from the Australian Science Media Centre.

"The beta particles, in particular, will cause serious damage to any surface that they coat. There would be initial reddening of the skin or tissue and, in severe cases, ulceration and potentially death of the tissues ("necrosis"). If swallowed it would potentially cause bleeding in the gut and ulceration which can lead to significant complications."

Another bad outcome is the capsule getting crushed on the road and the radioactive caesium being released into the environment.

"Clearly it's best if we can find the source and store it properly again," Obbard said. "But if it's never found, and it doesn't get broken somehow, then with a half-life of 30 years the Cs-137 inside will quietly decay away to Ba-137 which is not radioactive any more."

Mining company Rio Tinto, who the capsule belonged to, has apologized for losing the equipment. Around the size of a pea, the capsule—which is used in a radiation gauge at the mine to measure the density and flow of materials—could be anywhere on the route between the mine and Perth. Authorities have suggested that a bolt fitting shook loose on the journey, and the capsule fell out of the hole left by the bolt.

The 870 miles where the capsule could be—roughly equivalent to the distance between Washington D.C. and Orlando, Florida—are being searched using specialist radiation detection equipment that has been fitted to patrol vehicles. These vehicles will travel in both directions along the Great Northern Highway at speeds of 30 miles per hour. The painstaking search is expected to take five days.

An image of the capsule is below - pic.twitter.com/pbbtfZWEN9

— Chief Health Officer, Western Australia (@CHO_WAHealth) January 27, 2023

"Finding this lost source will not be easy; given the large distance involved, it will be akin to finding a needle in a haystack. Radiation detectors on moving vehicles can be used to detect radiation above the natural levels but the relatively low amount of radiation in the source means that they would have to 'sweep' the area relatively slowly," Bailey said.

There are some fears that the capsule may have moved out of the search zone, by being lodged in the tire of another car, or dispersed by birds or other animals.

"Anyone detecting radiation levels above the normal background should identify and seal off the potential site location with appropriate signage, maintain a large distance from the source and minimise the amount of time monitoring the radiation emitted and call the local EPA [Environmental Protection Agency]," Bailey said.

This is the second controversy associated with Rio Tinto in recent years: in 2020, Rio Tinto blasted land at Juukan Gorge in Western Australia to expand an iron ore mine, destroying 46,000-year-old sacred Aboriginal rock shelters in the process. Several of the company's top bosses stood down in the wake of the subsequent public outcry.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about radioactive material? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.