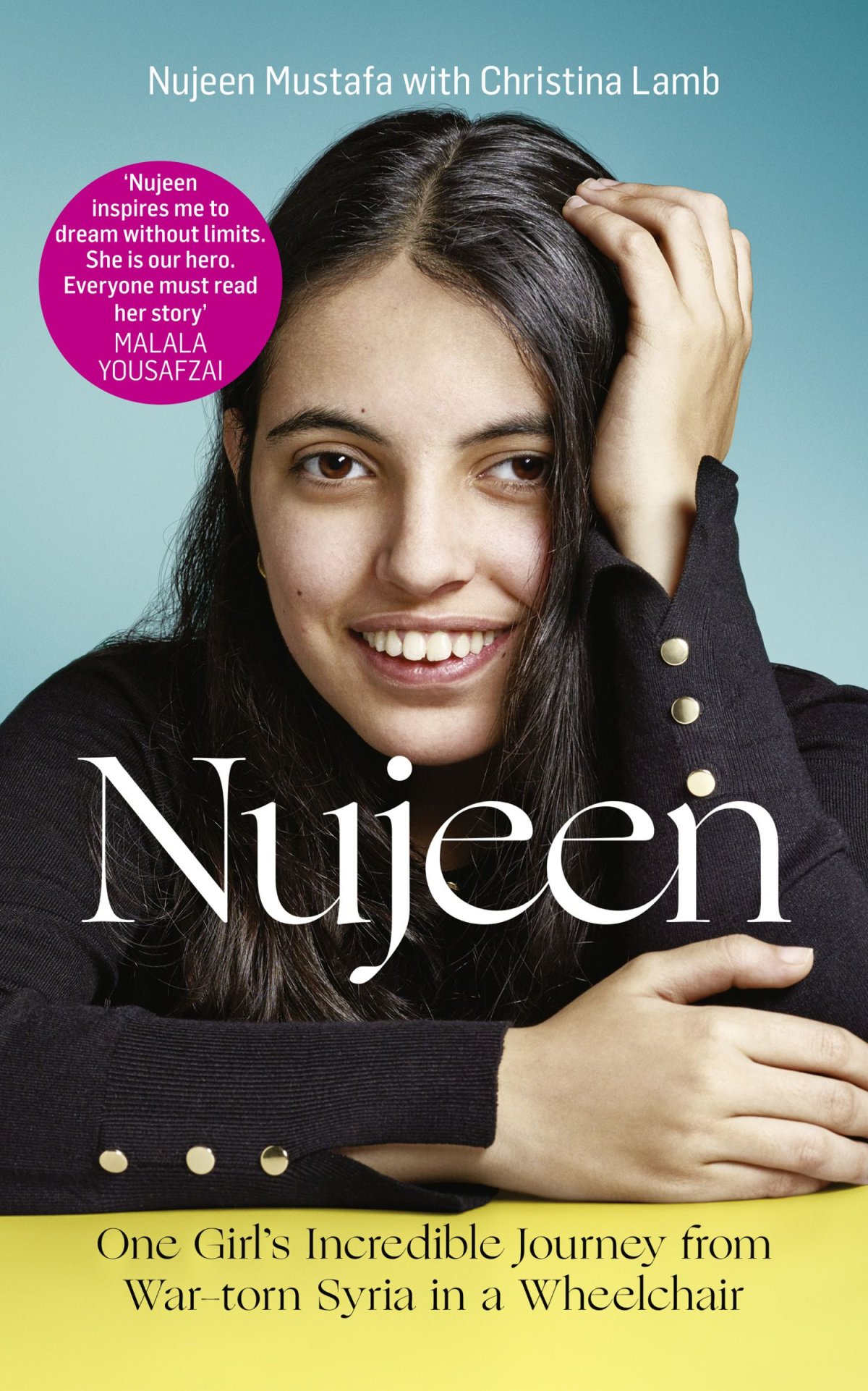

This is an edited extract of Nujeen: One Girl's Incredible Journey From War-Torn Syria in a Wheelchair by Nujeen Mustafa with Christina Lamb. (Published by William Collins, £16.99)

Behram, Turkey, September 2, 2015

It was the first time I had seen the sea. Back in Aleppo I had barely ever left our fifth-floor apartment. We had heard from those who had gone before that on a fine summer day like this with a working motor a dinghy takes just over an hour to cross the strait. It was one of the shortest routes from Turkey to Greece—just 8 miles.

The problem was that the motors were often old and cheap and strained for power with loads of 50 or 60 people, so the trips took three or four hours. On a rainy night when waves reached as high as 10 feet and tossed the boats like toys, sometimes they never made it and journeys of hope ended in a watery grave. The beach was not sandy but pebbly—impossible for my wheelchair. We could see we were in the right place from a ripped cardboard box printed with the words "Inflatable Rubber Dinghy; Made in China (Max Capacity 15 Pax)," as well as a trail of discarded belongings scattered along the shore like a kind of refugee flotsam and jetsam.

I was with two of my four elder sisters—Nahda, though she had her baby and three little girls—and my closest sister Nasrine. Also with us were some cousins whose parents—my aunt and uncle—had been shot dead by Daesh [ISIS] snipers in June when they went to a funeral in Kobane, a day I don't want to think about.

The way was bumpy. Everyone got very hot and bothered. The chair was too big for me and I gripped the sides so hard that my arms hurt and my bottom got bruised from the bumping. As with everywhere we had passed through I told my sisters some local information I had gathered before we left.

I was excited that on top of the hill above us was the ancient town of Assos which had a ruined temple to the goddess Athena and was where Aristotle once lived. My sisters didn't seem very interested. I gave up trying to inform them and watched the seagulls making noisy loops high in the sky. How I wished I could fly. Nasrine kept checking the Samsung smartphone our brother Mustafa had bought us to make sure we were following the Google map coordinates given to us by the smuggler. Yet, when we finally got to the shore, it turned out we were not in the right place. Every smuggler has their own "point"—we had strips of fabric tied round our wrists to identify us—and we were at the wrong one.

We had to walk up and down another hill. Those slopes were like hell. If you slipped and fell into the sea you'd definitely be dead. It was so rocky that I couldn't be pushed or pulled but had to be carried. My cousins teased me, "You are the Queen, Queen Nujeen!"

By the time we got to the right beach the sun was setting. We spent the night in the olive grove. Once the sun had gone the temperature dropped suddenly and the ground was hard and rocky even though Nasrine spread all the clothes we had around me. But I was terribly exhausted, having never spent so much time outside in my life, and I slept most of the night.

Breakfast was sugar cubes and Nutella, which might sound exciting but sucks when it's all you have. The smugglers had promised we would leave early in the morning and by dawn we were ready on the beach in our life jackets. Our phones were tied inside party balloons to protect them on the crossing, a trick we had been shown in İzmir. We had paid $1,500 each instead of the usual $1,000 to have a dinghy just for our family, but it seemed others would be in our boat. We would be 38 in total—27 adults and 11 children. Now we were here there was nothing we could do—we couldn't go back and people said the smugglers used knives and cattle prods on those who changed their minds. I knew the sea only from National Geographic documentaries and now it was as if I was part of one. I felt really wired and couldn't understand why everyone was nervous. For me it was like the biggest adventure!

There were people from Syria like us as well as from Iraq, Morocco and Afghanistan speaking in a language we didn't understand. As morning broke we watched the first boats go out. The boats didn't have pilots—the smugglers let one of the refugees travel for half price or for free if he drove the boat even though none of them had any experience. "It's just like riding a motorbike," they claimed. We'd heard that some refugees gun the motor to get halfway across to Greek waters as fast as possible. Sometimes the engines don't have enough fuel. If that happens the Turkish coastguard catch you and bring you back.

As the afternoon came, the waves started to get higher, making a slapping sound on the shore. None of us wanted to go at night as we'd heard stories of pirates on jet-skis who board boats in the dark to steal motors and the valuables of refugees. Finally, around 5 p.m., they said the coastguards were changing so we could take advantage and go. I looked again at the sea. A mist was coming down and the cry of the seagulls no longer seemed so joyful. A dark shadow lay over the rocky island. Some call that crossing rihlat al-moot , or the route of death. It would either deliver us to Europe or swallow us up. For the first time I felt scared. Back home I often watched a series called Brain Games , which showed how feelings of fear and panic are controlled by the brain, so I began practicing breathing deeply and telling myself over and over that I was strong.

Nujeen Mustafa will be in conversation with Naina Bajekal, executive editor of Newsweek Europe, on the Open Stage in the Agora at Frankfurt Book Fair on October 20.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.