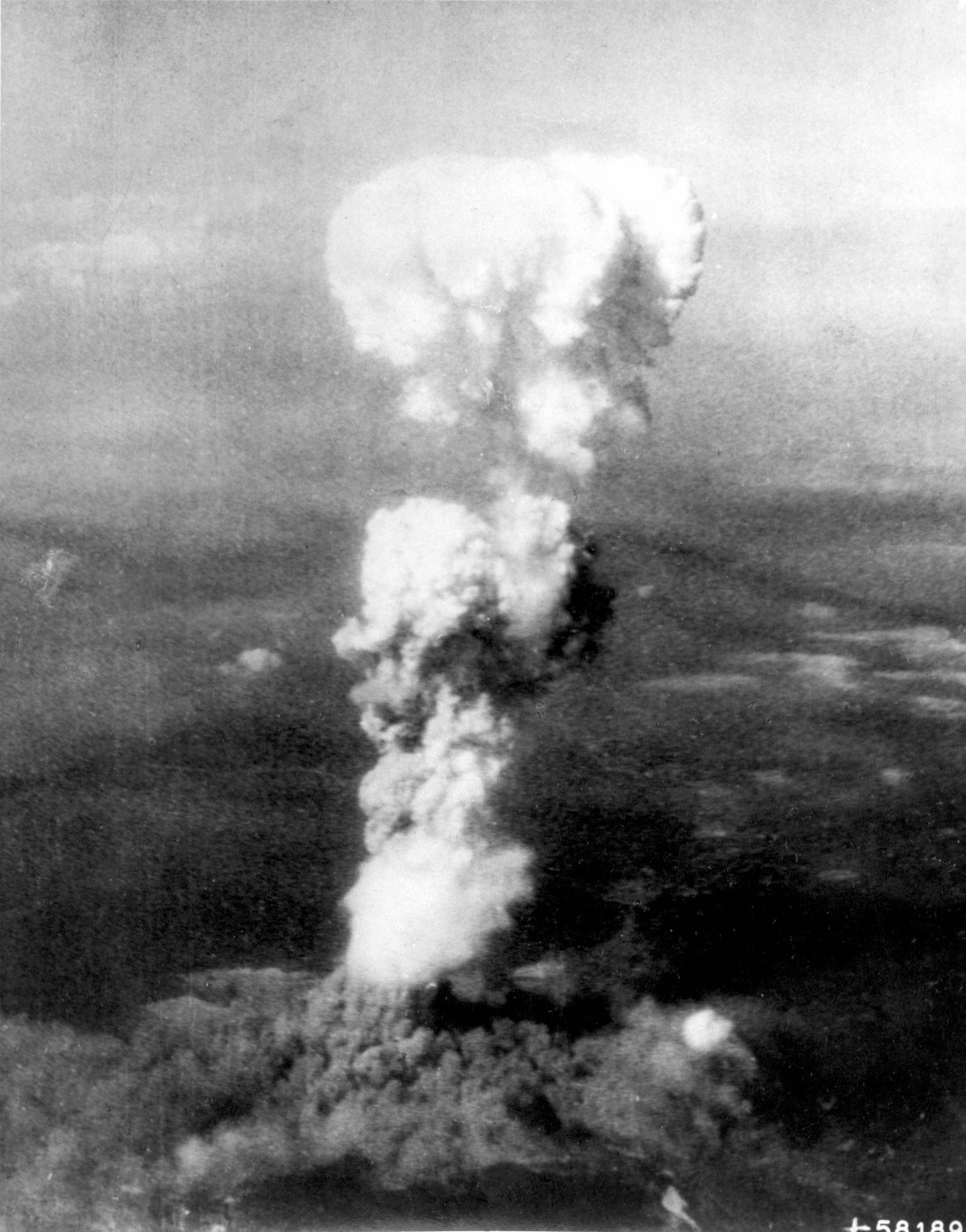

Seventy-three years ago today, the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan—a city of 350,000 people. The bomb flattened the city and killed tens of thousands in an instant. An hour after the blast, some 80,000 people were dead.

It was the first time any country had dropped an atomic bomb on another. Three days later, the U.S. dropped a second bomb on Nagasaki—a blast that killed tens of thousands more outright.

Many injured survivors languished for weeks and months. For many that survived the initial blasts, radiation sickness and cancer slowly crept through their bodies. Although it is impossible to know the exact number of lives cut short by the bombs, estimates reach 290,000.

As of March 2017, more than 160,000 hibakusha, the Japanese name for atomic bomb survivors, were still alive. A small sliver of this number have spent their lives retelling their stories in one of the most enduring political campaigns of our time.

In 2017, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) won the Nobel Peace Prize. Although the organization represents hundreds of groups around the world, it is hibakusha that have driven the movement—reminding the world of the intimate and indiscriminate devastation of nuclear warfare.

Survivors and their children have marked the bombings for decades by staging "die-ins," and and by releasing lanterns on the Motoyasu river by night, folding paper lanterns by the thousands and sitting in silence at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial whenever a nuclear test takes place somewhere in the world.

But it is the telling of firsthand accounts that has become the most enduring hibakusha legacy. Survivors around the world recount their experience at high schools, on television and even to politicians.

"The hibakusha were at the beginning of the story, and it is our collective challenge to ensure they will also witness the end of it," ICAN Executive Director Beatrice Fihn said at December's Nobel lecture. "They relive the painful past, over and over again, so that we may create a better future."

Two hibakusha—American citizens living in Hiroshima in 1945—retold their stories to Newsweek.

Howard Kakita was born in East Los Angeles in 1938. He had a mother, a father and an older brother called Kenny. In 1940, the family took a boat to Japan to visit Howard's ailing paternal grandfather. At this time, Howard's mother was pregnant with baby number three: Albert.

Depressed and drinking a little too much sake because his children lived so far away, Howard's grandfather's health miraculously improved when the young family came to stay. And so, when news arrived that Howard's parents' store in East Los Angeles was in trouble, they traveled back to the U.S. with Albert, leaving behind Howard and Kenny to keep their grandparents company.

On December 7, 1941, Japan launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the internment of Americans of Japanese descent after the bombing, and Howard's parents were sent to a camp in Poston, California. The two young boys didn't see their parents for seven years.

Howard was 7 and a half years old on the morning of August 6, 1945. School was closed because officials thought bombers might be hovering near the city, so the boys scrambled into summer clothes, excited for their day off.

When an air raid siren went off that morning, Kenny and Howard climbed up on the roof to watch for the vapor trails of the B-29 bombers. Their grandmother shouted at them to get the hell off the roof, and they scampered back down to the ground. Howard walked to the bathhouse and Kenny toward a gate at the front of their house. A gate that may well have saved his life.

By now, Colonel Paul W. Tibbets was flying the Enola Gay some 31,000 feet above their heads. The B-29 released a cargo unlike any other: a uranium bomb nicknamed Little Boy. The bomb fell through the sky for 44 seconds before exploding 1,900 feet above Hiroshima.

The boys lived just 0.8 miles from ground zero, and the blast knocked Howard out cold. He didn't hear the explosion that tore through the city. He didn't see the bomb's bright flash.

Moments later, he woke up under the rubble of the bathhouse. Flames were creeping up the charred, scattered debris.

Miraculously, both boys and their grandparents survived the explosion relatively unharmed. The blast sent shards of window glass into their grandmother's skin. There was a lot of blood, Howard recalls, but she was not seriously injured.

Meanwhile, at a munitions factory one and a half miles from the bomb's hypocenter, 16-year-old Junji Sarashina was crawling from a pile of rock, glass and sand. Unlike Howard, he had seen a bright orange flash before the blast knocked him to the ground. Also an American by birth, he had moved to Japan in 1937. A student at a local boarding school, he had been drafted to work at the factory during the war.

Junji ran to the factory first aid room, but found a nurse covered in blood. When he helped her remove a shard of glass from her mouth, he knew this had been no ordinary air raid. "I was very scared then," he said.

Junji and his classmates tried to cross a nearby bridge toward the city, but it was blocked by oncoming traffic. "That's when I saw burned people: skin hanging and no hair," he said.

A huge cloud of smoke had filled the sky. "The city of Hiroshima—it was burning," he said.

Meanwhile, the Kakita boys made their way toward a mountain area with their grandmother. They caught their first glimpse of the unique devastation of a nuclear bomb. Until now, they hadn't realized the extent of the damage. "None of us really knew how badly the city was destroyed," Howard said.

The boys passed many of the injured on a main road—skin practically dripping from their bodies. "Some people had guts hanging out from their stomachs, broken bones were evident all over," Howard said.

As they walked, they noticed soldiers had lined up rows of dead bodies in a nearby field. The sky had turned dark and radioactive, black rain pelted the survivors. A train took the boys and their grandmother to the safety of relatives in the countryside.

Howard's maternal grandparents were not so lucky. The sweet potato farmers had taken their produce into the city to sell on the morning of August 6. They were probably killed instantly. His uncle survived the blast, but suffered serious burns to his legs.

For Junji, the enduring memory of the bomb is of the charred bodies of a woman clinging to her child. On August 7, he and some fellow students finally made it across the bridge to the city—less than a mile from ground zero. Thousands of people with devastating burns were roaming what used to be the streets.

They searched the flattened city for their high school, which had vanished. Eventually, the students stumbled upon their school swimming pool, where a few younger kids, who had been swimming, were still in the water. Junji and friends tried to help them escape. "I grabbed their arms and pulled. The only thing that came out of the swimming pool was their skin," he said.

Junji and friends walked half a mile to the Red Cross Hospital, which was overwhelmed by terminally wounded patients. Recognizing students from his own school, Junji gave them blankets he'd peeled from the bodies of the dead and water he found on the hospital grounds. "One of them thanked me. But sooner or later, they all passed away."

Later on he traveled to his dormitory and gathered what possessions he could from the roommates he knew would never return. He wrote down the names of their former owners in the hopes their families would find them.

Families of the missing, he said, would become a second wave of victims.They would comb the streets of Hiroshima in the days following the bombings, looking for their loved ones. "One morning they'd get up, start to comb their hair and then realize [it] was stuck on the comb. They were exposed to radiation," he explained.

The next day, Junji returned home to his mother's place in the country. She cried when she saw him. He was weak and suffered diarrhea for days. But he was alive.

Imperial Japan surrendered to the U.S. on September 2, 1945—effectively ending World War II.

Howard, Kenny and their grandparents returned home soon after V-J day. The buildings were flattened—only concrete and metal structures remained. Month-old burned bodies lay among the rubble and the stench of mass cremations hung heavy in the air. The memory of the smell of burning flesh still makes Howard sick to his stomach. "It was pretty horrific escaping, but maybe even more horrific when we returned to see the bodies and the devastation of the area," he said.

The family lived in an old air raid shelter for weeks while they built a shack from materials that survived the blast. They developed serious dysentery and lost their hair. They survived on vegetables and eventually whale blubber distributed to survivors. "That was probably the only source of protein we had for a number of months," Howard said. His grandmother cooked up the blubber with sweet potato. "There were no gourmet meals in those days," he joked. "But it was something we survived on."

Back in the U.S., Howard and Kenny's parents were searching for their children, fearing the worst. It took them a month to track the boys down through the Red Cross.

After Howard's parents left their internment camp, they worked in Los Angeles and saved up for three years until they could afford to bring the two children home. Meanwhile, Howard and Kenny's grandfather succumbed to cancer.

War had also kept the brothers apart from their parents and younger brother for seven years. "That's another one of my brother and I's horrific experiences: We never knew our parents [growing up]," Howard said.

"When my grandmother told us we needed to go back to the U.S. to our parents, we raised holy hell. We just didn't want to leave to go and live with someone we never knew."

When they returned to the U.S., the boys struggled to integrate in their almost all-Caucasian, English-speaking town. "All we knew was Japan, and we spoke the Japanese language." But with time, the family began to heal. "Eventually we became a pretty good family. My parents were really wonderful. They were very patient with us," Howard said.

But for years, he suffered psychologically. Howard's mother would find him screaming in the middle of the night. Red foods—rare steak, tomato sauce, pink grapefruit—made him squirm with the memory of the carnage he witnessed back in Hiroshima.

A decade after the bomb was dropped, Howard stopped waking up in the middle of the night and he began to retell his story. Talking about his experience is therapeutic, he says.

Now more than ever, the two survivors are afraid of escalating nuclear activity. "It really worries me," Howard says. "People like Kim Jong Un in North Korea, Assad in Syria. People like this, if they had these weapons, I think they would use them. Is there any way to mitigate it? I doubt it, but I think I owe it to the people that were in Hiroshima that died.

"I always thought there was no way in the world that people in power would be dumb enough to start anything like that," he added. "But in recent years I'm beginning to think there are so many people that would use that stuff."

As the only true witnesses to the devastation of nuclear weapons, many hibakusha feel it is their duty to keep those stories alive to protect future generations.

"People should realize the horror of atomic war," Howard says. "I feel I owe it to society to at least share my experience and try to mitigate the proliferation of atomic warfare."

"That's my biggest wish—for world peace and a world without the use of atomic weapons," Junji says. "The entire human race should be aware of the effect of nuclear war."

For Junji Sarashina, one war was followed swiftly by another. He returned to the U.S. in 1950 after helping rebuild Hiroshima with his fellow high school students. He was drafted into the Korean War almost as soon as he made it to Hawaii. He used his language skills to interrogate and interpret in South Korea. After the war he moved to California and worked for Northrop Grumman for 30 years.

Howard Kakita went on to have a successful engineering career, before retiring 21 years ago. He has been married for more than 50 years and has two daughters and four grandchildren.

Now, he says, he loves rare steaks.

In Pictures: The World War II Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Katherine Hignett is a reporter based in London. She currently covers current affairs, health and science. Prior to joining Newsweek ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.