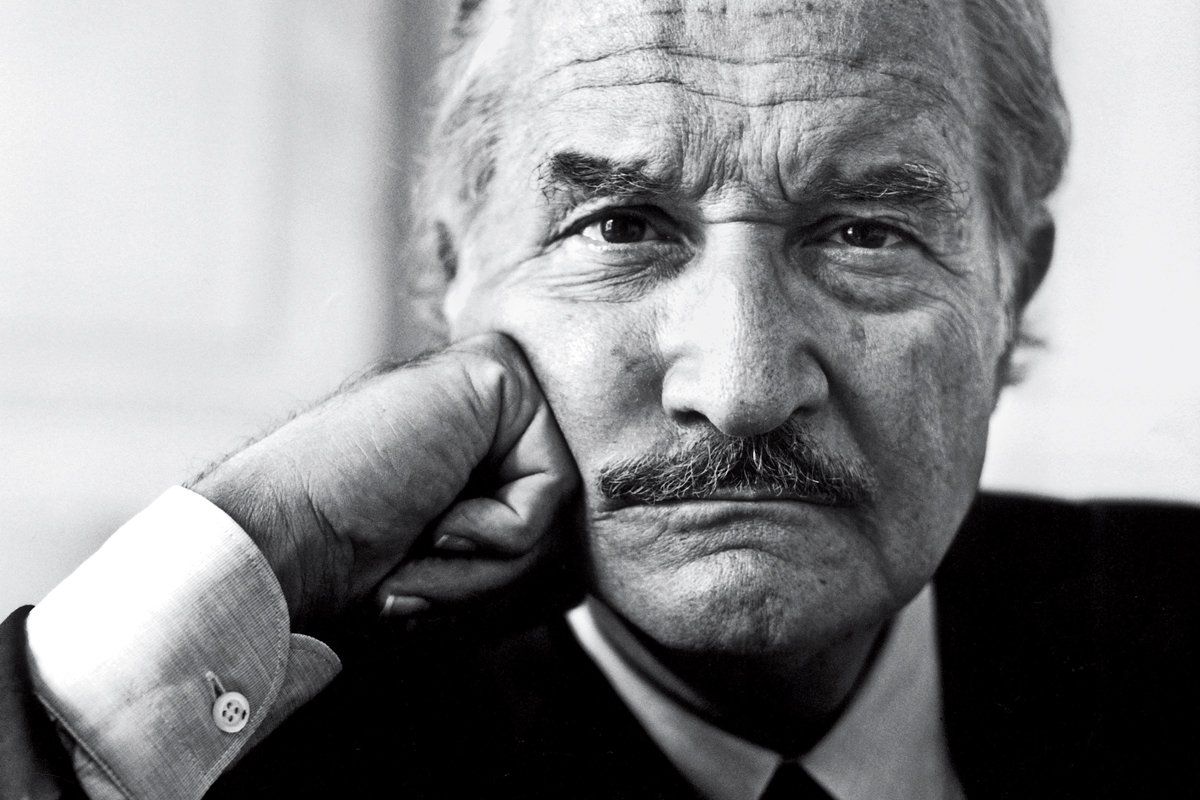

When Carlos Fuentes died last week, at age 83, the cultural world mourned the passing of a brilliant and passionate novelist. Fuentes was not just a prolific author, with some 60 novels, plays, and stories to his name, but also one of the icons of "El Boom," the Latin American literary explosion that swept the world in the 1960s and 1970s. He won every major honor in Spanish-language literature, enchanting readers from many continents. His tale The Old Gringo, about an aging American journalist (modeled on Ambrose Bierce) who rides off to fight beside the Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa, was adapted to film, starring Gregory Peck and Jane Fonda. And Americans swooned over his novella Aura, which transposed a Henry James story to the mesa.

But Fuentes's footprint stretches far beyond literature—to diplomacy, academia, and politics—parallel worlds that he navigated with ease and panache, whether in Mexico City, Paris, or Mazatlán. Polemical, occasionally quick-tempered, and fiercely outspoken, he staked out positions that sometimes jolted the establishment, helping himself on the written page or at the podium to the history and conflicts of Latin America. Fuentes was not a magical realist, eschewing the exotic, fantastical tale-telling made emblematic by his friend, Gabriel García Márquez. He compared himself to Balzac and had the dissecting eye of Dickens, his tales laying bare the horrors and distortions and lies of Mexico and its troubled courtship with the rest of the world.

Along the way he became the most famous Latin American of his day. Oddly, although he helped light the fuse of El Boom, Fuentes was passed over time and again as fellow writers García Márquez, Octavio Paz, and Mario Vargas Llosa won the Nobel Prize. But with his torrential output (written in longhand), his extensive career in foreign service (including as ambassador to France), and his commitment to telling his compatriots' story, he helped put not just Latin fiction but the whole of Latin America on the world map. Fuentes also had a mission, believing the great European and North American novel was flagging and that Latin American writers needed to step up. "He connected globalism and literature, perfecting the job of international man of letters," says the writer Ilan Stavans, an expert in Latin American literature at Amherst.

For all his worldliness, Fuentes at times seemed stuck in a political time warp, circa the 1960s. He openly praised Fidel Castro well after the Cuban tyrant had fallen out of favor with many other Latin intellectuals, including Llosa and Paz. He and William Styron famously smoked cigars with Nicaragua's Daniel Ortega, then a Marxist insurgent. Washington was not amused, and briefly banned his entry to the U.S.

But when the Cold War ended, he became a familiar figure in the U.S., touting translations of his books in flawless English, enchanting college students, and keeping company with notables and celebrities. (He admitted to having had affairs with actresses Jeanne Moreau and Jean Seberg.) A man of the left to the end, his last newspaper column, published the day he died, was a tribute to the return of a socialist to power in France. But Fuentes was not stuck in cement. He eventually spoke out against the hardening Castro regime, and famously dismissed Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chávez as a "a flatulent demagogue" and a "tropical Mussolini."

How much his writing will be remembered is an open question. Fuentes's international stature grew as his works lost their resonance at home. Though his prose is vivid and often elegant, Fuentes's fiction too seems to cling to the past, his tales clawing through the ruins of Mexican history for clues to his people's conflicted identity. "His novels are giant mythmaking machines, with characters ever struggling with their indigenous and European pasts," says Stavans. The fixation led him to stereotypes. Stavans calls him the Diego Rivera of letters, a reference to the early 20th-century modernist, known for his giant murals splashed with bold, often brutish tableaux of history.

In the modern, bustling, honking Mexico, such storytelling began to feel shopworn, like a sepia snapshot in a multiplex. It wasn't so much that the peripatetic citizen of the world had become un-Mexican but rather "too Mexican," says Stavans, committed to selling an image of a society that already had changed. "The new generation of writers rebelled against the myth-making."And that may be the ultimate homage to Fuentes, a writer who left more rebels than disciples. A master storyteller, Fuentes challenged the world to look at a people and a place it had never bothered to notice. Now that he's gotten their attention, Latin Americans can move on.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.