This article originally appeared on Medical Daily.

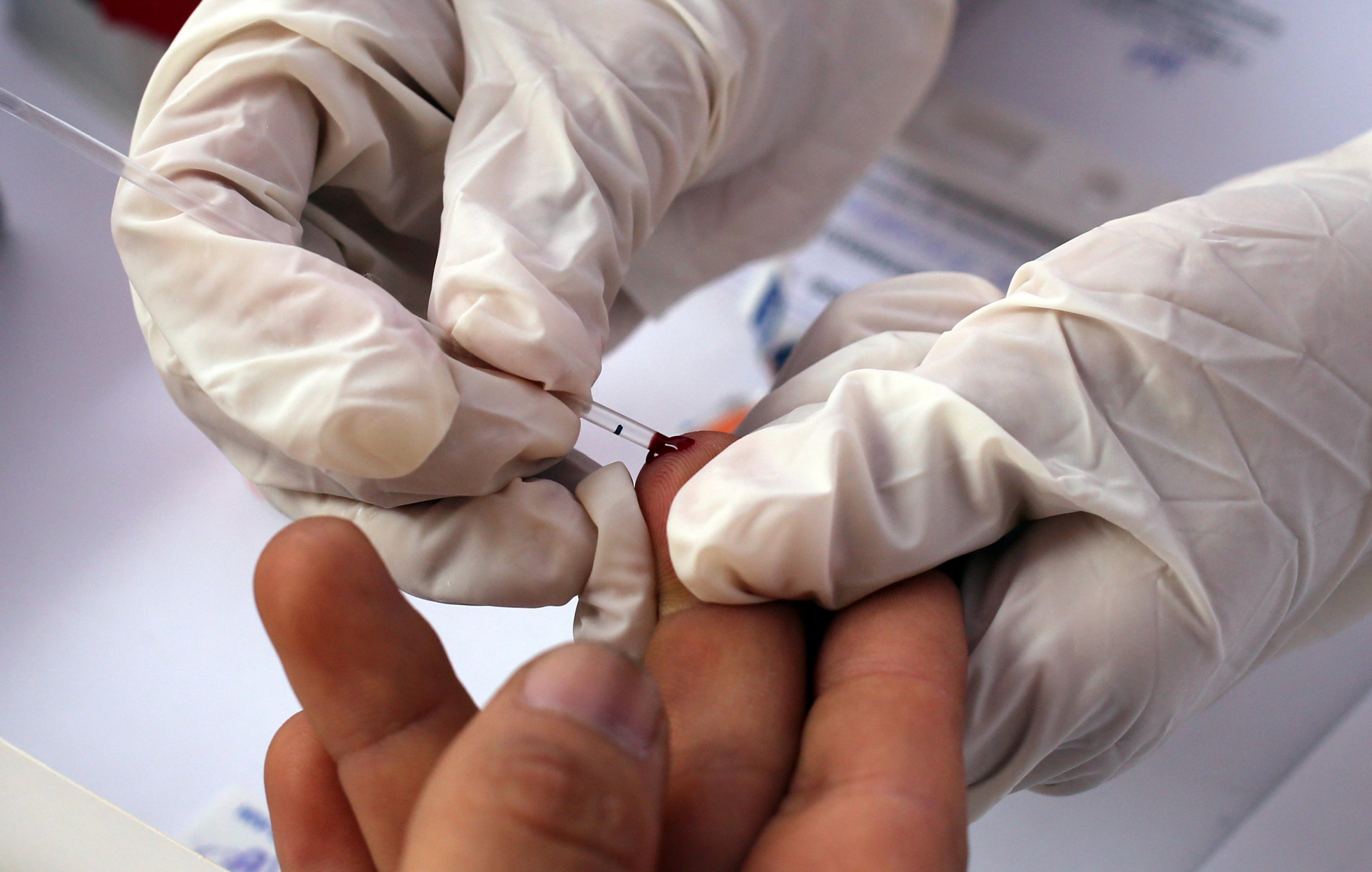

A cure for HIV has remained elusive, partly due to the virus' ability to hide and lie dormant in "reservoir cells." However, as explained in a recent study, scientists in France discovered a way to identify these dormant reservoir cells. This is a major step forward in eliminating the virus from the body, and potentially curing a patient of HIV.

According to the study, now published online in Nature, scientists succeeded in identifying a biological marker that sets healthy cells apart from dormant HIV-infected reservoir cells. Dormant HIV-infected cells and healthy cells look very much alike. This marker is a protein that is only found on the surface of HIV-infected cells, meaning if you can identify the protein, you can identify the hidden HIV. The finding, researchers note, could help doctors rid a patient's body of the virus, and lead to a possible cure.

After initial infection, HIV continues to reproduce inside of the body, destroying a patient's immune system and making them more vulnerable to other infections, according to a recent press release on the study on ScienceDaily. Although HIV treatments help to keep the virus numbers low enough to prevent it from doing any serious damage, these medications are not able to completely eliminate the virus from the body.

This is because the virus can lay dormant and undetected in some cells, and evade drugs. Once treatment has ceased, the virus can come back to life, replicate, and further wreak havoc on a patient's health. This is why antiviral treatment for HIV infections is required throughout a person's lifetime.

For the study, the team suspected that HIV might leave a mark on the surface of cells it infected, although they were not entirely sure what this mark might be. To find out, they studied the genes of models of HIV-infected cells and healthy cells, and noticed one tiny difference: The HIV-infected cells had a protein called CD32a expressed on their surfaces that healthy cells did not. The team then looked at the cell surfaces from human HIV-positive patients and noted the same presence of this protein on the cell surface. These results strongly suggest that the CD32a protein is in fact a marker for dormant HIV-infected cells.

The team has high hopes for their novel findings. For example, understanding how to reveal these HIV reservoirs could make it possible to directly isolate and eliminate the virus and do away with the need for life-long interventions.

In the meantime, antiviral treatments are still the most effective way to manage HIV infections. However, researchers are constantly working to make these treatments more effective and easier to take. For example, last summer a study may have revealed how HIV infects cells while simultaneously evading the patient's immune system, and hope to use this finding to develop new, more effective antiviral medications.

In addition, another study, also from 2016, may have figured out a way to combine existing antiviral therapies to create an antiviral regimen that could offer patients a lifetime of viral control after only six weeks of treatment.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.