The common belief is that pigeons are dirty, useless and kind of dumb. There are many—particularly New York City residents—who would go so far as call them rats with wings.

Around three years ago, Richard Levenson, a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at University of California Davis Health System, heard a compelling radio segment on the visual acuity of pigeons. A pigeon's brain is tiny, but it just so happens that the bird's neural pathways used for sight—the basal ganglia and cortical-striatal synapses—are as well-developed as ones found in humans. This means the birds have an especially fine-tuned visual memory. Levenson became captivated by the work of Edward Wasserman, professor of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Iowa, who has used the birds for years to study visual perception and cognition.

"Some of his more striking findings is they can tell the difference between early modern artists," says Levenson. "And they also can tell the difference between good child art and bad child art." (That talent, of course, is strictly based on the subjective taste of the researcher who trains the birds.) Other experiments have shown pigeons can distinguish between photos of a range of human emotional expressions and also letters of the alphabet.

"For no good reason it occurred me to ask if pigeons are visual, how are they with medical images?"

He reached out to Wasserman, and they agreed to collaborate on an experiment that used digitized slides of mammography imaging to see if the birds could earn their wings in pathology.

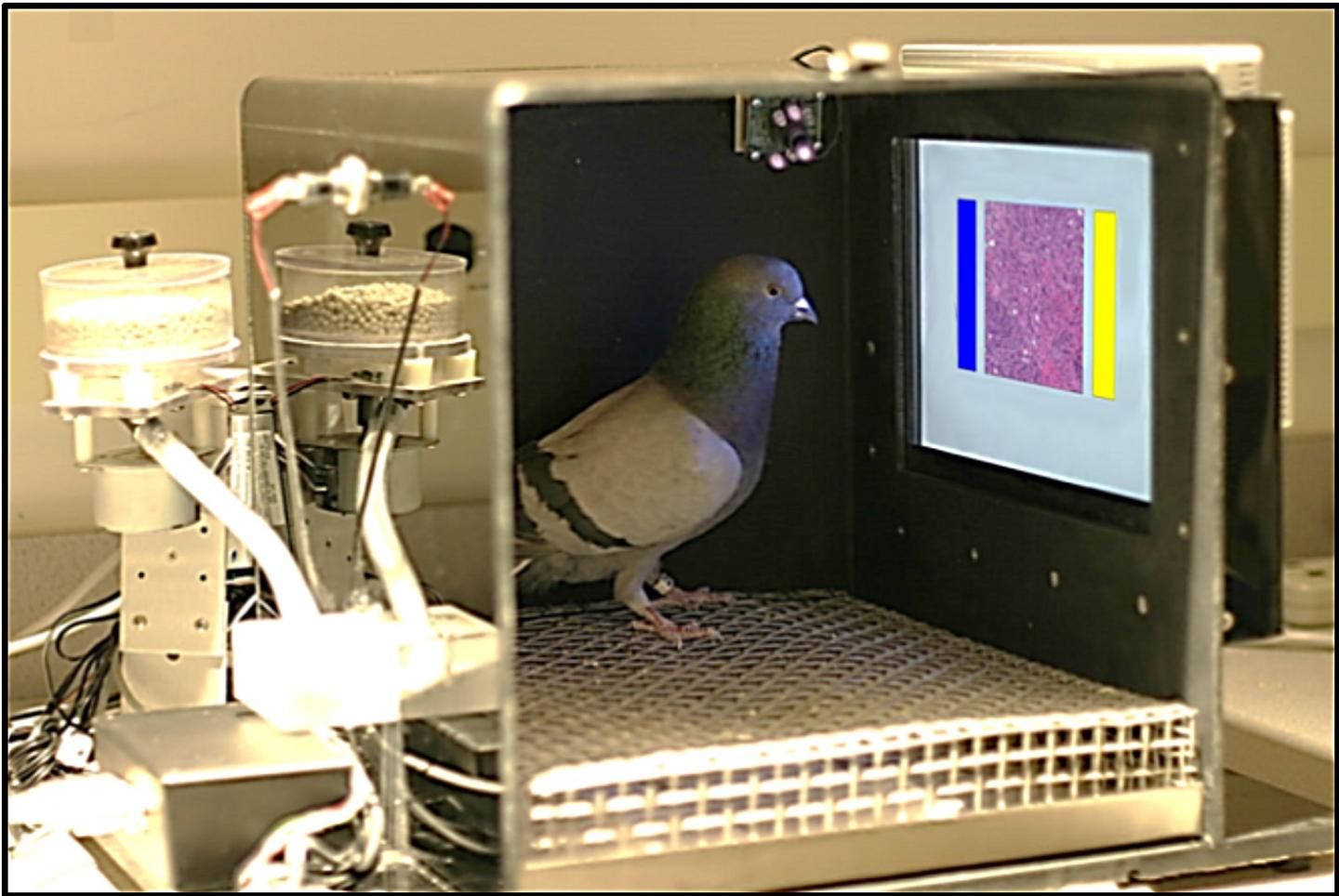

For the study, Levenson and his team trained eight Columba livia pigeons to identify certain colors and hues in parts of medical images that radiologists and oncologists look for when identifying breast tissue microcalcifications and malignancies. They used a food reward system, giving the birds 85 percent of their regular food beforehand and forcing the pigeons to earn the remaining 15 percent as part in the experiment.

They placed the pigeons in "conditioning chambers" in a darkened room with white noise. Each chamber came furnished with a food pellet dispenser attached to a fancy 15-inch LCD touch screen. But in this case, the screen was made for pecking, not touching. The team trained the birds to recognize certain visual attributes, such as benign or malignant samples in full color at low (4X), medium (10X) or high (20X) magnifications. When it pecked at the screen for the right image, the pigeon would receive a food reward.

In the low magnification experiments, the birds were right 50 percent of the time on the first day; by day 13 their accuracy improved to 85 percent. Overall the birds averaged about 84 percent for identifying microcalcifications and 72 percent for irregularities in images, a similar success rate that is normally achieved by a licensed radiologist. However, the pigeons didn't get such high marks when faced with the task of differentiating between imaging of benign and malignant breast tissue.

Levenson says the experiments defy our perception of the intelligence of these creatures. "It doesn't fit in with our narrative of what they are," he says. "'Bird brains' is pejorative."

Don't worry. A pigeon won't soon be replacing your oncologist.

"Let's put off the table that pigeons could make breast cancer diagnoses. It's not that they couldn't, but it's that I don't think society would be ready for that," says Levenson, who is the lead author on the study published earlier this week in PLOS One. "Fortunately there are good reasons to pursue this work."

The reasons have nothing to do with stupid pet tricks on late night talk shows. It turns out scientists could use the fine-tuned visual memory skills of the birds to develop and improve new medical imaging devices.

When new technologies are created, they need to be validated by the naked eye, which requires a painstaking process of sifting through hundreds of images. This job is usually carried out by clinicians who require a high salary and don't have enough time (or patience).

The birds could be a suitable employee to take on this arduous task. "I'm pretty confident that pigeons can play that role," says Levenson. "The animals could help fine tune how bright, how much contrast, what resolution you present images at the end. The pigeons can do a lot of the intermediate and heavy lifting. It will be faster, cheaper and more accurate."

How's that for bird brains?

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jessica Firger is a staff writer at Newsweek, where she covers all things health. She previously worked as a health editor ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.