If Fido doesn't want to fetch or eat, if he's sneezing or coughing or has a fever, he might have the flu. Like humans, birds, pigs and horses, dogs can catch the influenza virus and quickly spread it to other dogs.

The first canine influenza vaccine in the U.S. was approved in 2009, about five years after the first dog-specific strain was identified in racing greyhounds in Florida and then thousands of dogs of all types in several states. The H3N8 canine influenza virus evolved from an equine strain that had been infecting horses since the 1960s, says Cynda Crawford, a veterinarian and clinical assistant professor at the University of Florida who helped discover it. Another strain, the H3N2 canine influenza virus—which was adapted from an avian influenza and had been circulating in dogs in China, Korea and Thailand—appeared in Chicago in March 2015.

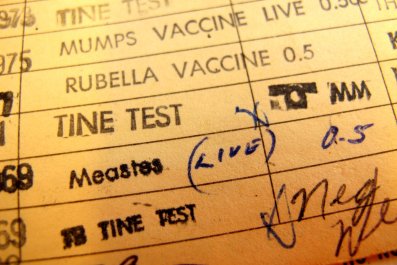

The vaccines currently available for both strains are killed, or inactivated, vaccines that contain a dead virus. They require two shots a few weeks apart, and a booster every subsequent year is recommended.

But "nobody likes needles, including dogs," says Luis Martinez-Sobrido, an associate professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Rochester who led the research on live-attenuated (also called modified live) influenza vaccines (LAIVs). Martinez-Sobrido and his fellow Rochester researchers, along with colleagues at Cornell University and the University of Glasgow, recently found several ways they might make live-attenuated influenza vaccines for dogs.

One paper, published in the Journal of Virology, describes the introduction of five mutations to the H3N8 virus that are used to create LAIVs for human influenza, such as FluMist, taken as a nasal spray in one dose instead of multiple injections. The tested mice displayed stronger immune responses and fought off subsequent infections better than those given an inactivated vaccine. For the group's second paper, published in Virology, they tried a process that has been used in human, swine and equine viruses to produce an immune response without causing illness: the complete deletion, as well as three kinds of truncations, of the NS1 protein in the virus. The team is working on similar experiments developing LAIVs for the H3N2 virus, which Crawford says has spread more rapidly, infecting thousands of dogs in at least 30 states in less than two years.

"I've been waiting a long time for something like this, as a veterinarian and dog owner," says Crawford, who thinks the team's methodology is solid and its results promising. But he predicts getting approval will be the most difficult step. "I think the USDA will be much more scrutinizing about this," compared with a killed vaccine, because of the potential for dogs to become mixing vessels if they are infected with a human influenza virus, which dogs can get but not spread, around the time of vaccination.

"Influenza viruses are known for promiscuous gene sharing," Crawford says, which "could create a third, new virus with the capacity to infect both dogs and people or cause more serious disease."