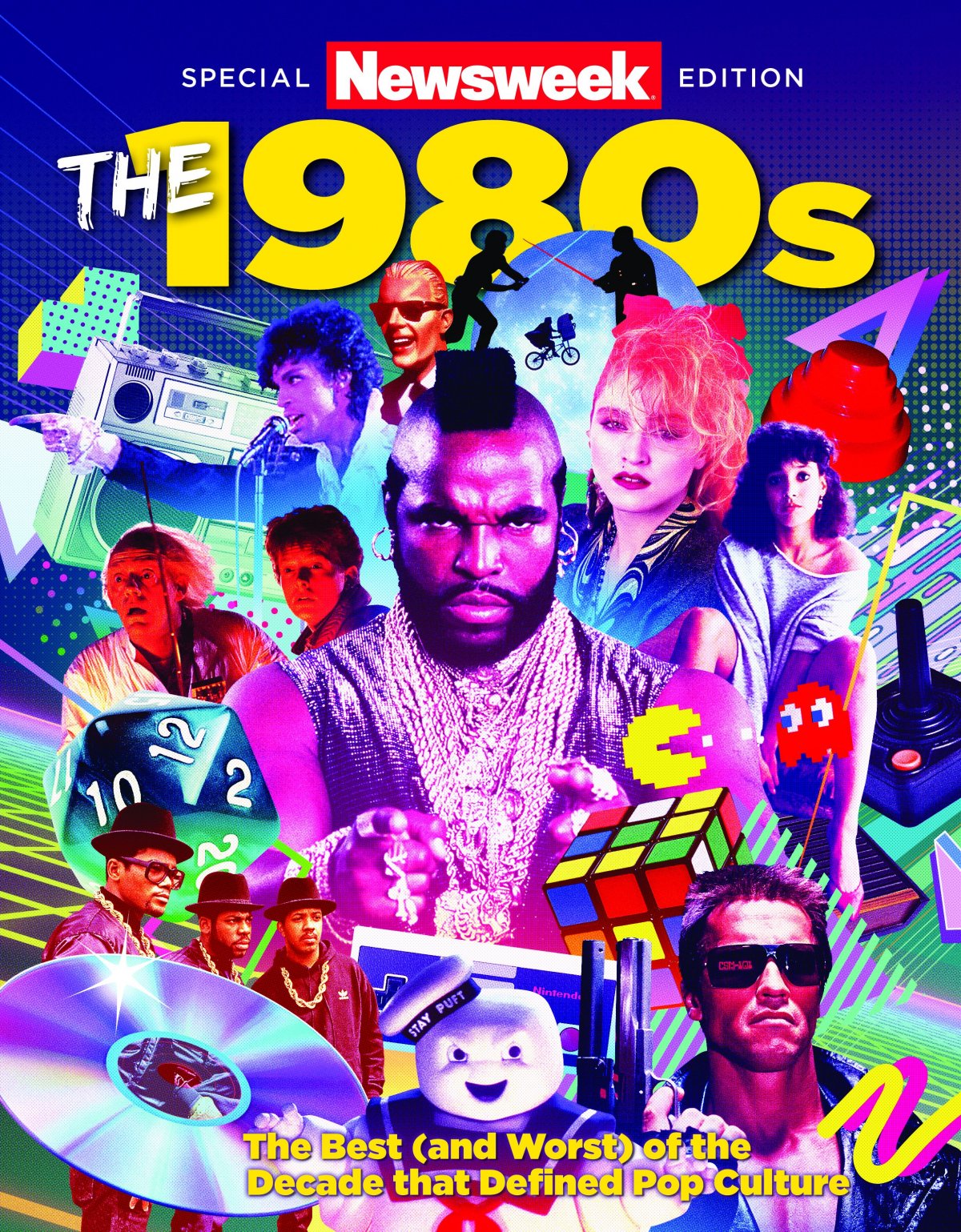

This article, along with others of the best (and worst) of the decade that defined pop culture, is featured in Newsweek's Special Edition: The 1980s

Nostalgia is, most simply if not most eloquently described, comfort food to nurse our existential crises. As long as there have been humans, there have been introspective impulses toward a time that, while in reality just as complicated and nuanced as our own, seems easier to deal with thanks to the cultural touchstones available. Any medieval scholar worth his or her salt, for example, could tell you the most common motif in the popular literature of the middle ages was a yearning for the golden age of Camelot.

Arthur's court is imagined to be based on events from a few hundred years before the proliferation of his story through Europe. Since then, communication has become faster and faster and the gap between our nostalgic "golden ages" has shrunk accordingly up to the modern age. By the 1970s and early 1980s, TV shows like Happy Days, films like American Graffiti, Grease and Porky's and the birth of '50s-style diners such as Johnny Rockets—not to mention the fact that a wholesome '50s movie star was president—made the Eisenhower years seem halcyon. This trend reached its peak when, in 1985, Marty McFly found himself transported (goose down vest, Walkman and all) to 1955. This tendency toward the '50s has drawn the ire of academics ever since it began. The nostalgic impulse's basest practitioners seemed to be hijacking a natural human emotion to foster love for the Jim Crow era, and the impulse was disdained for it.

In his Back to the Fifties: Pop Nostalgia in the Reagan Era, Michael Dwyer painted a lighter picture by arguing that "Fifties nostalgia in the Reagan Era must be understood not as a reduction or denial of history but rather as a productive practice…The nostalgia...must be understood not as a quality inherent to specifi c texts, but rather as a quality of the relation between the text, the adjacent texts that surround it, and audiences." In other words, nostalgia is one of the main ways in which people interact with their cultures.

Thirty years later, we again seem to be looking backward for our cultural meat and potatoes. With Ready Player One—a full-length indulgence in all things '80s written by a guy who actually drives a DeLorean—getting more Americans to crack open a book than anything since The Hunger Games, and Stranger Things tugging at the "Remember When" cortexes of every 1980s kid's brain, anecdotal evidence suggests there's a Reaganera renaissance saturating our pop landscape.

Max Landis, a successful young screenwriter and the son of '80s auteur John Landis, is currently at work penning a remake of his father's 1981 horror hit An American Werewolf in London. Stephen King's IT, a blockbuster book written in the '80s—but with half its action placed in the '50s—saw its most recent film adaptation (for which there will almost assuredly be a sequel) shift the action forward to the decade in which the book was originally written. Dwayne Johnson, a throwback action star with the body of Arnold Schwarzenegger and the background of Hulk Hogan, is Hollywood's most bankable personality, and his list of credits past, present and future reads like a rundown of '80s pop culture touchstones: G.I. Joe; Baywatch; Rampage; Big Trouble in Little China. Were the properties and personalities of the '80s simply better than those of every other decade, or is this merely a question of timing?

As Amanda Ann Klein and R. Barton Palmer put it in their Cycles, Sequels, Spin-offs, Remakes, and Reboots: Multiplicities in Film and Television, "[Modern] commercial cinema and television have been essentially defined by the genres, series, remakes, adaptations, reboots and spin-offs that enable the continuing provision of a sameness marked indelibly by di erence." To put it simply, everything old is new again, and everything new retains the stamp of the old.

So why is the nostalgic well from which American culture is drawing at this particular moment labeled "1980–1989"? Part of the answer has to do with the most prolific contributors to the culture of the 1980s also being around for its re-imagining. Steven Spielberg, for example, is responsible for some of the most popular intellectual property of the decade—Indiana Jones, E.T. and The Goonies, just to name a few—and is also at the helm of the film version of Ready Player One, placing him squarely at the top of the '80s nostalgia pyramid.

There is also the shape of the 1980s film business to consider. The '80s were the decade our modern conception of what a blockbuster is, when it should be released and how it should be marketed took definite shape. Perhaps most importantly, the 1980s killed the Old Hollywood idea that lightning couldn't strike twice.

Old school studio moguls saw films as individual commodities—each a separate gamble. A sequel or remake would only be a vain attempt to stem the tide of folks clamoring for something new. They didn't want to make last year's movie, they wanted to make next year's. By the 1980s, unstoppable sequels such as The Empire Strikes Back and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom were proving that fan-favorite follow-ups, with their locked-in audience and proven IP, were the future. Ever since, the film franchise—rather than single entries—has become the norm.

For those who grew up in the 1980s, this reinforcement of what exactly constituted our pop canon meant unprecedented exposure to the characters their TVs and movie screens were making them attached to. Not only did they go to the movies and enjoy Ghostbusters in 1984, they could count on Ghostbusters 2 and The Real Ghostbusters to be there. The advent of VHS meant the cinema wasn't the final destination for a film, but was instead its jumping-off point into living rooms across the country. Characters were no longer simply the dramatis personae in our entertainment—they became our babysitters and best friends. Children effectively raised by their pop culture heroes are now old enough to make movies of their own. And because of the financial risk involved with creating a major studio release, the films they are increasingly being asked to create are throwbacks to or reboots of the content they consumed as kids.

These factors—innovation in the 1980s film industry, '80s kids reaching their creative peaks and the fi lm industry's constant fear of gambling on anything new—have created a perfect storm of '80s nostalgia. Ghostbusters, adventurous archaeologists, DeLoreans and Air Jordan 1s bombard us from our many screens, and for the most part we can't get enough. In five years, that storm may blow over to allow for a '90s front to move in. In the meantime, we can revel in the glow of series that pay homage to the era (including The Goldbergs, Stranger Things and G.L.O.W.) and thrill at the sequels to stories that peaked in the '80s (Tron; Star Wars; Blade Runner) created by filmmakers who grew up immersed in them. Perhaps 30 years from now we'll be clamoring for a reboot of these nostalgic reboots (or—if Ready Player One proves prophetic—living inside them). Just count us out of a future Back to the Future remake that sends Doc and Marty back to 1985. Some things are just too meta for their own good.

This article was excerpted from Newsweek Special Edition: The 1980s. For more on the biggest moments of the iconic decade pick up a copy today.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.