Updated | Marian Kotleba used to wear a uniform modeled on the militia of Slovakia's wartime Nazi puppet state. He opposes Western democracy, the European Union and NATO. He rails against the Roma people and openly admires Jozef Tiso, the Catholic priest and wartime leader who permitted tens of thousands of Jews to be deported to Nazi death camps.

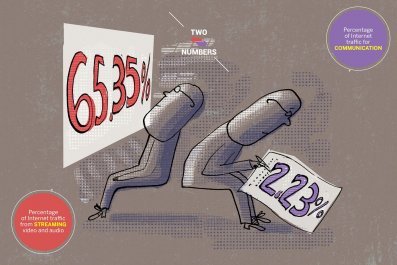

In the post–World War II era, European politics have seen a long series of extremists, generally raging on the sidelines and creating a lot of noise while wielding limited power. But Kotleba, the leader of the extreme-right People's Party-Our Slovakia, is no longer confined to the fringes. More than 200,000 people voted for his party in elections on March 5, including 23 percent of first-time voters, giving it 14 seats in the 150-member parliament.

Kotleba's triumph—the party was previously unrepresented in parliament—shocked many people in Europe. Slovakia was supposed to be one of the European Union's success stories. The country split off from Czechoslovakia and became independent in 1993. In recent years, it has joined the eurozone, enjoyed healthy economic growth—3.7 percent in 2015—and increased consumption and foreign investment.

Many blamed the anti-immigrant rhetoric of Prime Minister Robert Fico for the rise of the extreme right. Fico, a left-wing populist, had repeatedly vowed to protect Slovakia from an influx of Muslims, even though Slovakia is not on the main routes that refugees and migrants take to get from the Balkans to Germany—and few, if any, of them want to live there. Fico said Slovakia would take in 200 Syrian refugees—as long as they were Christian.

In an echo of billionaire real estate magnate Donald Trump's campaign for the U.S. presidency, Kotleba has harnessed a growing anger in Slovakia at the political establishment. "Our Slovakia is the only party that is against the system," says Milan Nic, director of the Central European Policy Institute, a Bratislava think tank. "There is very little trust, and people believe that the whole political class is corrupted."

Something deeper and more disturbing is stirring across Central and Eastern Europe, say analysts. Back in what now feel like the halcyon days of the 1990s, millions of people in countries that had until recently been under the control of the Soviet Union were suddenly full of optimism. European Union membership, it was hoped, would put a chicken in every pot and replace the Trabants in the garage with at least a Volkswagen, and possibly even a BMW or Mercedes.

While EU membership has stabilized the former Soviet bloc, it has also opened the door to a new kind of crony capitalism, as politicians quickly learned that they could divert funds to friends and allies with little, if any, sanctions from Brussels. Corruption is widespread. Hungary and Slovakia rank lower than Namibia, Rwanda and Saudi Arabia on Transparency International's 2015 Corruption Perceptions Index. At the same time, national leaders are developing a new kind of what critics call "managed democracy," where voting remains free and fair, but the independent institutions that guarantee citizens' rights are increasingly brought under political control.

In late February, for example, Istvan Nyako, a Hungarian Socialist politician, arrived at the National Election Office in Budapest to submit a referendum question about Sunday shop closures. He was blocked by a dozen burly skinheads and prevented from handing in his request. Instead, officials accepted a similar request from the wife of a mayor previously allied to the governing Fidesz party. "I felt terrorized, intimidated and threatened," Nyako told the Associated Press. "When I tried to file my questions, I was blocked and pushed aside."

The referendum request by the wife that officials accepted was complicated in its phrasing, obscured the question and is unlikely to rally those who want to see shops open on Sunday. The closure of shops on Sunday is deeply unpopular, and the government would almost certainly lose a referendum on this issue.

Hungarian media reported that the security guards were connected to Ferencváros, a football club whose president, Gábor Kubatov, is also a vice president of Fidesz. Fidesz denied any connection to the events, as did Ferencváros. Kubatov also condemned the incident.

Gellért Rajcsányi, a journalist at Mandiner.hu, a conservative news website, called Nyako's experience a "revolting mockery of Hungarian democracy." Eva Balogh, at Hungarian Spectrum, a left-wing blog, called it a "day of infamy."

Others were less surprised. "I expected something like this to happen sooner or later," says Tamás Boros, co-director and head of strategy of Policy Solutions, a Budapest think tank. "Such tactics are commonplace in the Balkans. This shows the Hungarian political system should not be compared to Western ones, but to the Balkans."

Government officials reject such claims. Hungary remains a genuinely lively democracy, with a free media and independent safeguards, say officials. But a 2014 speech by Viktor Orbán, the right-wing prime minister, made many Hungarians wonder how much longer the fully open form of government would last. In July of that year, Orbán proclaimed that while Hungary would remain a democracy it would be an "illiberal state." In the same speech, he praised Russia, China and Turkey as examples of successful nations.

Orbán's speech was misunderstood, says György Schöpflin, a Fidesz member of the European Parliament. It was not a rejection of democracy, but of liberal democracy. "The combination of liberalism and democracy is exhausted," says Schöpflin. "There are other kinds of democracy than liberal democracy: social democracy, Christian democracy. These are part of the democratic family."

Either way, Orbán's speech certainly resonated in Warsaw. After Poland's socially conservative Law and Justice party won parliamentary elections in October 2015, it immediately began to consolidate power by taking over formerly independent institutions. Jaroslaw Kaczynski, the party leader and arguably the most powerful person in Poland, had had plenty of time to plan. After losing an election in 2011, Kaczynski declared: "There will be a day when we will have a Budapest in Warsaw."

Like Orbán, Kaczynski believes his mission is to finish the job that began with the fall of Communism by re-engineering the political system. That means clearing out old Communist-era networks the party believes still hold sway in national institutions. Kaczynski's allies quickly brought the constitutional court, the civil service and state broadcasting to heel. The heads of the intelligence service, the Warsaw Stock Exchange and several state companies were replaced.

Kaczynski and Orbán have another thing in common: Both are vocal opponents of admitting Muslim migrants and refugees. In October, Kaczynski publicly said they carry "parasites and protozoa." Orbán visited his Polish counterpart in January 2016, and the two men spent six hours in a guesthouse on the Polish-Slovak border.

"You can see the influence of what happened in Hungary," says Filip Pazderski, a project manager at the Institute of Public Affairs, a Warsaw think tank. "It's not a direct implementation, but it's there in the core. Poland has changed its direction."

The EU is doing what it can to stop the democratically elected governments of some of its member states eroding the independence of their own national institutions. But this is uncharted territory, and it can't do much. A stinging report from the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe (a regional intergovernmental organization) said Law and Justice's reforms to the Polish Constitutional Court posed a danger to the rule of law and "the functioning of the democratic system." Article 7 of the EU treaty, which allows for the suspension of member states, is known as the "nuclear option" and has never been used. Nor does anyone seriously expect that step to be taken against any country. The Polish government, meanwhile, says it has a clear mandate for radical change. (Law and Justice is the first political party in Poland to win an outright majority since the change of the political system in 1991.)

Poland's swing to the right is being watched with growing concern in Berlin, says Julian Rappold, a program officer at the German Council on Foreign Relations. "Poland was seen as a vital partner. But now, with the change of government and the anti-German rhetoric, it's a much more difficult relationship. German policy-makers have to find a balance in criticizing constitutional changes and restrictions on press freedom, but also acknowledge that this is a freely elected government."

Conservative politicians deny that the region is regressing. "The incident involving Jozsef Nyako was unacceptable but was a one-off, says Schöpflin. "The real issue is the Western countries' need continually to point the finger at another country and make a fuss about supposed extremism there, in order to divert attention from their own political problems."

Continually highlighting the supposed shortcomings of Central and Eastern Europe is a kind of cultural imperialism, says Schöpflin. "It must always be a country to the east, so they can say, yes, things here are imperfect, but look how much worse they are in Hungary, or wherever, so be grateful that you live here and not there. But this is not a real place they are talking about—it's an imagined construct."

Others disagree. More than 2,000 letters have been sent to Andrzej Duda, the Polish president, demanding that he strip Jan Gross, a leading Polish-American Holocaust historian, of the country's Order of Merit. Gross's sin? Highlighting Polish complicity with the Nazis during the Holocaust and arguing that Poles killed more Jews than they did Germans during the war. We should be worried, says Boros. A fever is spreading across the region. "If more and more people do not believe that the political elite represents them," he says, "they will turn to extremist forces."

This article originally incorrectly stated that Istvan Nyako was Jozsef Nyako and that he was still a member of Parliament, and referred to a former Fidesz mayor instead of a mayor who was formerly allied to Fidesz.