The plans were ready; the $250,000 payoff cash was committed. On December 10, 2018, a former Air Force intelligence officer named Bob Kent was planning to board a plane in New York for the Middle East on a most improbable secret mission: freeing Robert Levinson from Iran.

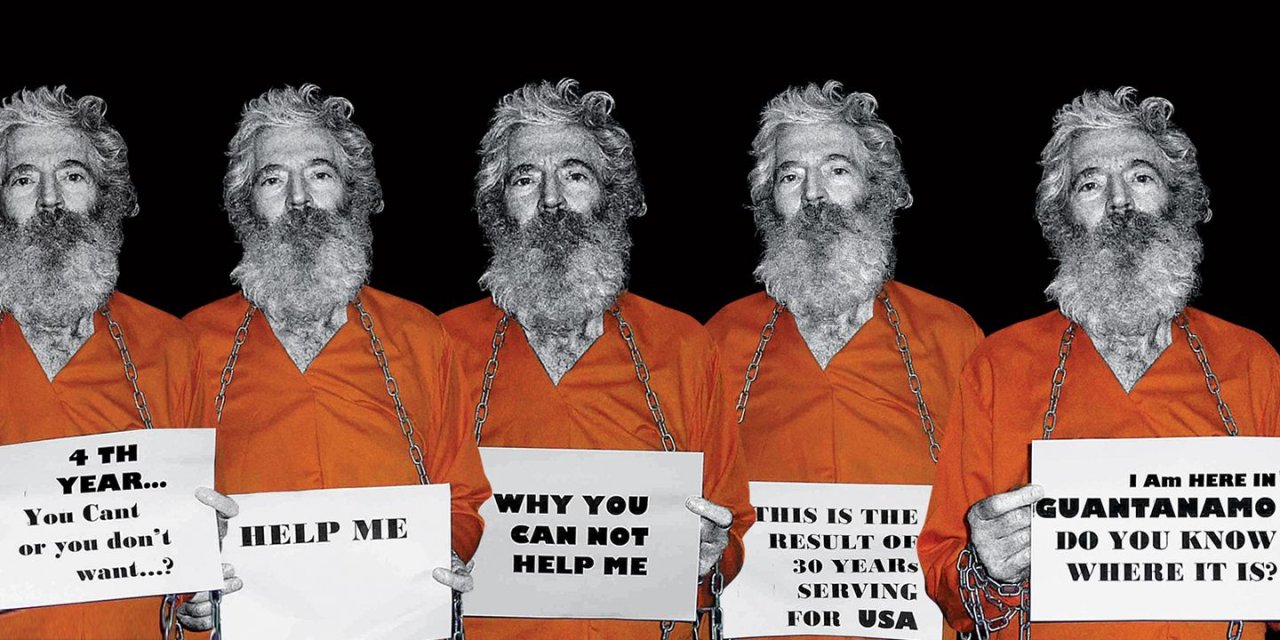

Levinson, an ex–FBI agent well into a second career as a private detective, had disappeared over a decade earlier from a hotel on Iran's Kish Island. He had been seen only twice since then, first in a hostage video his family received from unknown intermediaries in 2010, then in photos three years later, showing the then-63-year-old increasingly haggard and begging for help.

At first, the U.S. government claimed it had no knowledge of why Levinson, an expert on Russian organized crime, had gone to Iran. The Iranian regime denied it was holding him. But in 2013, the Associated Press and other news outlets revealed that the ex-agent had gone to Kish on an off-the-books CIA mission to probe high-level Iranian money laundering.

To the Levinson family, that explained why the government had not adequately pursued his release over the years, or in a prisoner swap the Obama administration conducted with Iran: He was an embarrassment to both the FBI and CIA. The possibility also existed that rival factions in Iran had not been able to agree on his release after years of denying it had him.

Desperate, the family put its own plans in motion to win his release. In doing so, they shared the plight of scores of families whose loved ones had been snatched by the Iranians (or Hezbollah, their Lebanese proxy) over the decades, including, at present, four other Americans and a U.S. permanent resident held by Iran. Levinson's past FBI employment, and then revelations of his murky CIA mission, lent his case more gravity, of course, not to mention mystery. But in 2013, Levinson earned yet another dubious distinction: He became the longest held U.S. hostage in American history. March 9 will mark the 12th anniversary of his disappearance.

And what a tangled web his case inspired. Kent would be just the latest in a chain of unlikely players in the hunt for the missing man, including a onetime Iranian assassin, a retired detective with CIA connections, an ex–FBI agent, a former federal prosecutor, a Philadelphia truck driver and Russian mobsters.

"For years, there's been a steady parade of well-meaning, crazy and even corrupt people who have tried to help the Levinson family or tried to use Bob's case to help themselves," Barry Meier, author of 2016's Missing Man: The American Spy Who Vanished in Iran, tells Newsweek. "It's enough to make your head spin."

Kent's mission, like all the other private efforts to locate and win Levinson's release, came to nil. Not for lack of resources—money men "with CIA connections," as three sources involved in the case described them, had offered to pay Kent's Iranian helpers $100,000 for a proof-of-life package, including fingerprints, a blood sample and what they claimed was a recent, 41-second video clip of Levinson, who would be 71 on March 10. "Another $150,000" would be needed "for the rescue," Kent says. But just as Kent readied to leave for the airport three months ago, the federal government got in the way, he says, refusing to issue the Americans a waiver from the Trump administration's sanctions on Iran to permit the payments.

"I received a phone call informing me that the funding was withdrawn because the State Department and/or FBI threatened my sponsors" with prosecution, Kent tells Newsweek.

To Levinson family attorney David McGee, a former federal prosecutor who had several meetings with government officials on the case over the years, the last-minute abort of Kent's mission fit a long pattern of official neglect and sometimes outright interference in efforts to free the former FBI agent.

"I am continually astounded and dismayed at the failure of the government of the United States, through three administrations, to bring Bob Levinson home," McGee tells Newsweek. "He was taken by enemies of this country while in its service. There is no moral justification for their failure to do what is necessary to bring him home."

The FBI took sharp umbrage at McGee's judgment. "While we cannot discuss how we handle particular investigations, over the past 12 years, the FBI has worked diligently to follow every credible lead to determine the whereabouts of Bob Levinson and will continue to do so," the bureau says in a statement to Newsweek. "Bob spent 22 years serving as an FBI special agent, and as we mark the anniversary of his disappearance, our resolve to find him only increases."

Meanwhile, the bureau has posted a $5 million reward for "information that could lead to Bob Levinson's safe return."

Kent, who had been collecting threat intelligence for corporate clients in the Middle East for several years since his 2007 Air Force discharge, got involved in the Levinson case last April "in response to an informal FBI inquiry," he says. He had been tracking the movements of Iranian operatives, particularly Saif al-Adel, an Egyptian-born militant on the FBI's Most Wanted Terrorists list suspected of working for Iran's Revolutionary Guard.

Hoping to land a government intelligence contract, he reached out to FBI counterterrorism agents. But they were skeptical about his sources, he says; as a kind of test, they "sarcastically" told him to "find Bob Levinson." Two months later, he came back with assurances he could obtain proof-of-life evidence and perhaps even more.

Kent's main FBI contact (a counterterrorism agent whose name Newsweek is withholding at the bureau's request) "thanked me for sharing my information, promised to investigate the background information I shared and told me repeatedly that arranging the proof-of-life meeting in Iraq would be 'incredibly complex,'" Kent says. The agent said he would get back with an update within 10 days. He also "recommended I not contact McGee," Kent says—the FBI privately dismisses the lawyer as "a meddler"—but Kent rejected the suggestion. Since July, he's been "working for McGee pro bono," he says.

Months went by without further word from the FBI. A group in Northern Virginia "with ties to the CIA" that had volunteered to finance the proof-of-life mission—and whom Kent, McGee and others involved declined to identify—was standing by. But as it turns out, moneymen have often been attracted to the Levinson cause—some of it from troubling sources.

One such was Oleg Deripaska, the Russian aluminum tycoon who would be sanctioned by the Treasury Department in 2018 for "a range of malign activity around the globe." A decade earlier, hoping he might earn points toward solving his visa problems with the U.S., "Deripaska announced he was willing to fund a search [for Levinson] and pay any ransom needed to free Bob," according to Meier's authoritative account. "Bureau officials were elated." In the end, nothing came of it.

The same offer came from an even more odious Russian figure with U.S. legal problems. Notorious mobster Semion Mogilevich, who occupies a spot on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list in connection with an alleged massive stock swindle, telegraphed U.S. officials through intermediaries that he would finance a Levinson rescue effort. The involvement of Mogilevich, often dubbed "the most dangerous criminal in the world," was hugely ironic: As an FBI agent and private investigator, Levinson had been tracking Mogilevich for years. "I don't know his motivation," Kent says of Mogilevich, but "he backed out."

"We had several other people offer to put up the money," Kent adds, provided they could persuade the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), which administers and enforces economic and financial sanctions, to grant them a waiver.

They couldn't. But soon after Kent's aborted December trip, McGee met with FBI agents and sensed a new, more cooperative mood at the bureau. He came away thinking the FBI was going to help fund the $100,000 proof-of-life payment—after it vetted the material as genuine—but those prospects soon dissolved. Then, in an early February meeting, Kent and McGee had with several officials at the State Department, Robert O'Brien, the special presidential envoy for hostage affairs, told them that if OFAC cleared the deal and the Defense Department authorized it, the Joint Special Operations Command might be able to assist with the Levinson mission.

McGee soon got a personal meeting scheduled with a sanctions official at Treasury to pursue the waiver issue. At the last minute, however, the department canceled the February 8 appointment. "We were back to square one," McGee says. (A Treasury spokesman asked that Newsweek not identify the official by name and refused to discuss the case further.) Kent's appeals to various congressional offices were also fruitless.

Meanwhile, another private group was angling to locate Levinson, this one sparked by a most unlikely character. Walton Martin, a Philadelphia-area truck driver and former Marine, tells Newsweek he became obsessed with Iran during the 1979-81 hostage crisis, in which revolutionary-minded students in Tehran stormed the U.S. Embassy and captured 52 U.S. diplomats and citizens. Eventually, he launched a one-man project to aid Iranian defectors and refugees in Turkey, working closely with the U.N. high commissioner for refugees' office in the capital city of Ankara.

Over time, he developed a constant stream of intelligence from inside Iran, some of it related to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard's operations and, eventually, on Levinson's purported whereabouts. He began sharing it with the FBI. They developed a close relationship, judging by several emails Martin shared with Newsweek.

His FBI handlers, whose names Newsweek is withholding out of concern for their personal safety, were excited. "There is a definite 'buzz' in the govt about our missing friend," one of the agents told him in a July 27, 2017, email, "and part of it is you working nonstop on it—I am relaying everything you are telling me to the people that need it."

Martin eventually found his way to yet others working privately on Levinson. One was Joseph O'Brien, a former FBI agent who had led the bureau's 1980s investigation of Paul Castellano, head of the Gambino crime family. He had considered Levinson a mentor when they worked together in New York. In 2016, O'Brien and another ex–FBI colleague offered the bureau help on Levinson with their own Iranian-exile contacts but were rebuffed. "They told us to get lost, basically," O'Brien told Newsweek last year.

Eventually, Martin and O'Brien began working together and getting their own reports from inside Iran on Levinson's purported whereabouts and offers of proof-of-life evidence—but, as with McGee and Kent, for a price. Now, the government demanded to know what they had and how they got it. Martin, wary of the FBI's handling of the case, refused. On February 22, 2018, he was subpoenaed by Tejpal Chawla, an assistant U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, demanding he appear before a grand jury with "all letters, correspondence and reports related to" Levinson's "whereabouts, condition and location." In a tense meeting with Justice Department officials, Martin handed over his information, and the subpoena was withdrawn. O'Brien says he later delivered packages of their Iranian reports to the offices of Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and White House national security adviser John Bolton. They got no response, but the FBI later told Martin it was "skeptical" about the authenticity of his Iranian sources and reports. (A Farsi speaker who examined a handful of the reports for Newsweek identified some of them as "obvious forgeries.")

Martin is bitter about his treatment by the FBI. "I don't work on a one-way street and to be frank, the Bureau will need to subpoena me again before they get a damn thing from me," he told McGee in an email he shared with Newsweek. "I'm working to get Bob home and I will NOT willingly submit to threats, intimidation or interference from anyone, including USG and FBI. We are much closer to bringing Bob home than the Bureau is."

But O'Brien, partnered with Martin, persisted with developing sources in Iran. They were also joined by a retired Washington, D.C., detective who had worked on counterterrorism cases with the CIA and FBI. The detective, who asked not to be named because of his continuing government work, tells Newsweek that in the spring of 2018 he met with Abolfazl Bahram Nahidian, a radical Virginia imam who is considered close to Iran and whose contacts might offer a back channel on Levinson.

One of the imam's contacts, according to the detective, was David Belfield, an African-American convert to Islam who had taken the name Dawud Salahuddin and in 1980 carried out an assassination of an anti-regime activist in Potomac, Maryland. Decades later in Iran, he was offering himself up to journalists and others as a source of information and analysis on the regime.

It was Salahuddin whom Levinson flew to Kish Island to meet in March 2007, to discuss high-level Iranian money laundering abroad. And it was Salahuddin whom Levinson's wife, Christine, reached out to after he disappeared. But the imam claimed to have no specific knowledge of the Levinson affair and referred the detective to the Pakistan Embassy, which handles Iran's affairs in Washington, D.C.

Salahuddin had insisted to Christine that he had nothing to do with her husband's disappearance; Iranian agents had hustled him from the hotel where they met. He himself had suffered from their connection, Salahuddin said, with authorities refusing to give him a new passport or internal travel documents.

A former senior intelligence official responsible for Iran tells Newsweek the government believes, privately, that Levinson is dead. Officially, it maintains he's alive, with the FBI calling the 12th anniversary of his disappearance "an opportunity for the leadership of the government of Iran to demonstrate its commitment to basic freedoms and civil rights and return Mr. Levinson home to his family."

But Christine Levinson says the government has let her down. "Time and time again, Bob has been left behind, deprioritized or seemingly forgotten," she told the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on the Middle East, North Africa and International Terrorism on March 7.

"My husband served this country tirelessly for decades," she said. "He deserves better from all of us and from our government. He deserves our endless pursuit to bring him home, to fight day and night and leave no stone unturned."