Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe, was calm but tense on Wednesday. Tanks and military vehicles were deployed in parts of the city, but residents continued to go about their business.

Nevertheless Evan Mawarire, a Harare-based pastor who leads the #ThisFlag protest movement, tells Newsweek that Zimbabweans are aware of the magnitude of what is going on. "From the outward appearance, things are going on as normal, but people are definitely aware of what is...[happening] in the nation," Mawarire tells Newsweek from Harare.

Zimbabwe's capital witnessed its most remarkable day in decades on Wednesday. Early in the morning, the military rolled into the state-run Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC), placed a spokesman in front of the camera, and informed the country that it was pursuing "criminals" surrounding Robert Mugabe, the nation's president since Zimbabwe gained independence, in 1980.

By the end of the day, Mugabe was confirmed to be under house arrest; troops were patrolling the capital; and reports abounded of negotiations to see the 93-year-old president hand over power, possibly to Emmerson Mnangagwa, his former vice president and the man Mugabe fired unexpectedly last week.

The day's events appear to represent an inglorious end to Mugabe's reign of almost four decades in the southern African country. Zimbabweans—generations of whom have never known another political leader—have watched as their homeland has been transformed from the breadbasket of Africa to an economic basket case, where the currency has collapsed and the central bank has begun printing notes with no value outside the country.

"The unfortunate thing about President Mugabe's legacy is that it leaves more of a bad taste in the mouths of the people of Zimbabwe than a good one," says Mawarire.

Read more: Who is Emmerson Mnangagwa, the man who may be Zimbabwe's next president?

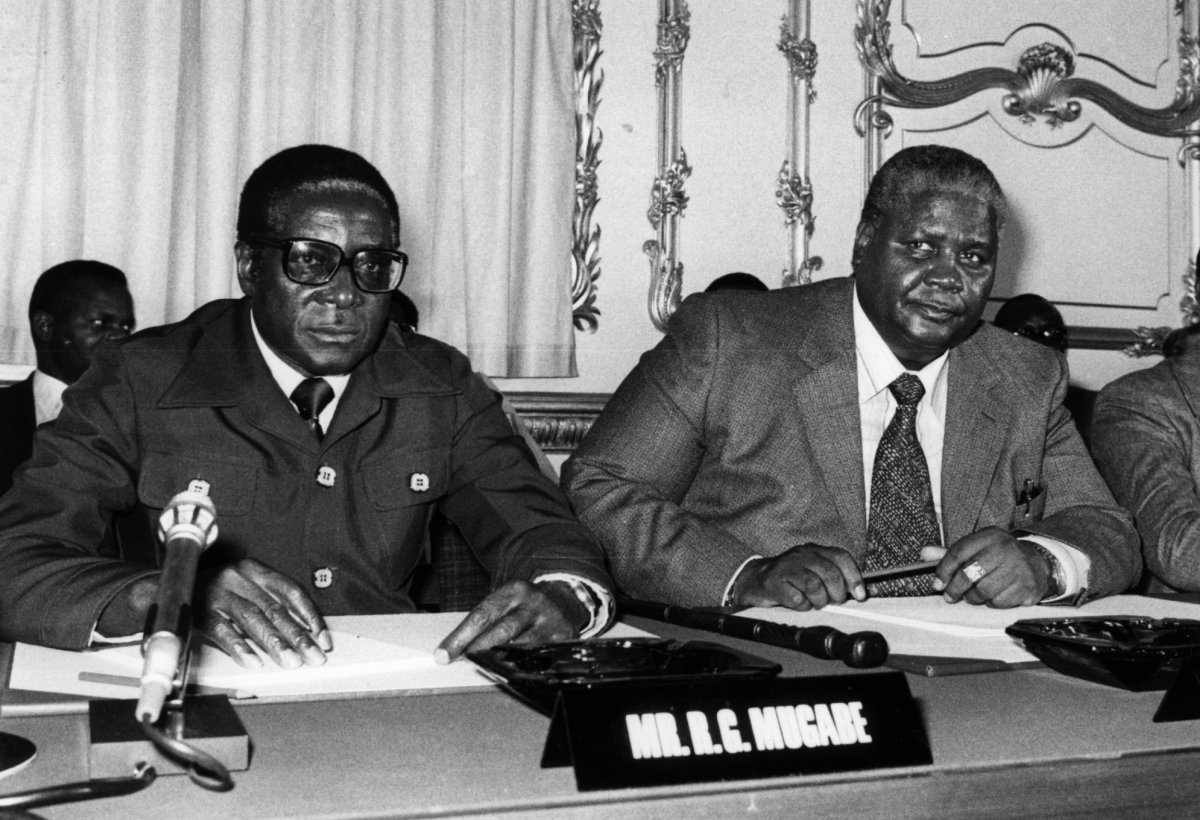

But despite his apparent ousting, Mugabe continues to command enormous respect in Zimbabwe, particularly for his role as chief liberator in the country's war of independence against the white-rule government of what was then Rhodesia, a former British colony. A Marxist and African nationalist, Mugabe set up a militant organization while in exile in the 1970s and returned to fight against white-minority rule. The war culminated in a British-mediated peace agreement and an election in 1980 that saw Mugabe voted in as prime minister; he would later assume the presidency in 1987, a role he has held until the present day.

In the early years of his leadership, Mugabe pledged to reconcile and rebuild Zimbabwe. He appointed white ministers to his government. He also oversaw a huge expansion in the country's health and education sectors, the dividends of which continue to pay off: Zimbabwe has an adult literacy rate of at least 83.6 percent, one of the highest in Africa.

But Mugabe's first decade of leadership also provided a brutal example of the authoritarian streak for which he has become renowned. Between 1983 and 1987, Mugabe oversaw a period of savage massacres in which a North Korean–trained army unit—which reported directly to Mugabe—suppressed political and ethnic opposition to the government in Zimbabwe's western provinces of Matabeleland.

The massacres are known as Gukurahundi—a term in the Shona language that roughly translates to "the early rain which washes away the chaff before the spring rains." Estimates of the death toll vary, with some saying it was as high as 20,000. But Mugabe avoided international condemnation for the massacres—visiting the Ronald Reagan White House in September 1983—and has failed to take responsibility for the killings, previously describing it as a "moment of madness" that was perpetrated by both sides. (Mnangagwa, who was minister of national security at the time of Gukurahundi, denies responsibility for the killings.)

Gukurahundi is by far the worst aspect of Mugabe's legacy in Zimbabwe, according to Derek Matyszak, a senior research consultant at the Institute of Security Studies (ISS), a South African think tank. "This was ethnic cleansing, Mugabe is basically a génocidaire, and people have tried to airbrush that aspect of his background, but there's no getting away from it," says Matyszak, who is based in Harare.

While the Gukurahundi massacres live long in the memory of Zimbabweans, it was Mugabe's controversial land-reform policies that most vividly captured the attention—and outrage—of the West. Starting in 2000, the Zimbabwe government backed the forcible seizure of white-owned land, despite them being ruled as illegal by the country's Supreme Court. Mugabe stoked racial tensions, saying that the land had originally been stolen by white settlers and Africans were simply taking back what was theirs. "The white man is not indigenous to Africa. Africa is for Africans, Zimbabwe is for Zimbabweans," the president stated.

The land seizures resulted in several white farmers being murdered and many more forced from their homes and property. Yet Mugabe has remained unrepentant, saying as recently as August, "We will never prosecute those who killed [white landowners]."

One of those killed was Mike Campbell, a white Zimbabwean farmer who took Mugabe to court over the land seizures. Campbell and his British son-in-law, Ben Freeth, were abducted and beaten in 2008 by pro-Mugabe attackers; Campbell died three years later from his injuries.

Freeth has since set up a foundation in his father-in-law's name and is seeking justice for white farmers killed in Zimbabwe and South Africa. He says that—despite Mugabe's recent comments about not prosecuting the killers—the Zimbabwe president's possible departure reinforces his faith that he will see justice.

"At the end of the day, Mugabe is 93 years old. He is possibly going to be out of power by the end of the day. We don't know, but he's not going to last forever," Freeth tells Newsweek from Harare, where he is based. "He's not going to be around to make sure that those assurances are kept in the future, and justice is a much bigger thing than the promises of tyrants."

Mugabe's program of land seizures—while benefiting some poor black Zimbabweans—is widely seen as having contributed to Zimbabwe's catastrophic economic collapse in recent years. Western donors cut aid and sanctioned government figures after the reforms were implemented, while many of those who seized the land were untrained in agriculture, leading to a massive drop in productivity.

The economic crisis became particularly acute in 2008, when a period of massive hyperinflation saw prices doubling nearly every day and eventually resulted in the Zimbabwean dollar being abandoned in 2009. And while Zimbabwe's economy has stabilized somewhat since then, unemployment remains high, food remains scarce, and the country's central bank is so short on foreign exchange that it began printing a pseudo currency in 2016. Bond notes, as they are known, have no value outside Zimbabwe and have raised fears of a second period of hyperinflation.

Zimbabwe's socioeconomic woes are what prompted Mawarire, the pastor, to set up the #ThisFlag movement. It has gained massive attention on social media, orchestrated a national shutdown in July 2016, and seen Mawarire charged with trying to subvert the government. (He is due back in court later in November.)

Mawarire says that Mugabe's recent legacy is one of the "decimation of our economy and our infrastructure" and the "plundering of our natural resources," and that whoever takes over must ensure an immediate improvement. "What Zimbabweans want is not a very difficult thing. Zimbabweans want a country that works," he says.

The man who looks most likely to take up that task is Mnangagwa, who is in his 70s but whose exact age is a matter of dispute. A war veteran and ally of Mugabe's for decades, Mnangagwa was the president's deputy from 2014 until November 6, when he was dismissed amid accusations of disrespect and deceit.

Mnangagwa's departure appeared to be the explosive result of factionalization in the ruling Zimbabwe African Nation Union–Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) party, which has long been split into factions—one backing Mnangagwa and the other the first lady, Grace Mugabe, to succeed Mugabe. The president's dismissal of his deputy was widely seen as a step toward creating a Mugabe dynasty and handing power to his wife, but Mnangagwa's strong backing among the military appears to have motivated Wednesday's extraordinary events.

The military takeover has left ZANU–PF facing a purge, with some of those loyal to Grace Mugabe reportedly being arrested on Wednesday. But Justice Mayor Wadyajena, a ZANU–PF MP in northern Zimbabwe, insists that the party is simply undergoing a "leadership renewal."

Wadyajena, who describes Mnangagwa as a "political mentor," says that Mugabe's position is no longer tenable and that the party must rally behind Mnangagwa, the man known as the Crocodile in Zimbabwe. "He is the only man I believe that has not just the vision but also the political will to rescue the nation's economy," Wadyajena tells Newsweek.

Zimbabwe's immediate future remains unclear. Mugabe remains stuck in his home in Harare, as South African delegates head to the country to negotiate with both sides. The leader of the African Union has condemned the military takeover, while Western powers have remained conspicuously muted on Mugabe's apparent demise.

But should these be the last days of Mugabe, Zimbabwe must focus on what lies ahead, says Mawarire. "We have always dreamed of a Zimbabwe that allows its citizens to be free. That is the one word. If you asked me what do Zimbabweans want today, Zimbabweans want to be free," he says. "The Zimbabwean dream has got to be a reality going forward."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Conor is a staff writer for Newsweek covering Africa, with a focus on Nigeria, security and conflict.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.