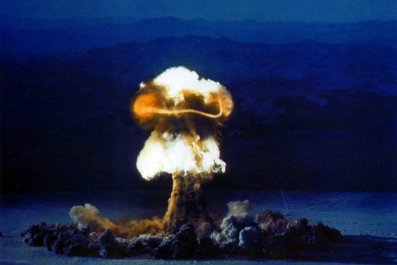

As the Iraq war turned into an unmitigated, bloody disaster, another disaster was unfolding in newsrooms around the world: Ad sales plummeted, and print subscriptions dried up thanks to all the free content on the internet. While Marines and Iraqi civilians bled out in Mosul, newsrooms hemorrhaged red ink.

Massive layoffs commenced, and many small-town papers shut their doors. But some of the most devastating casualties of this media catastrophe were foreign bureaus. When Sarah Glidden went to Turkey, Iraq and Syria in 2010 for her book Rolling Blackouts —the follow-up to her award-winning 2011 debut, How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less —these changes were already well underway.

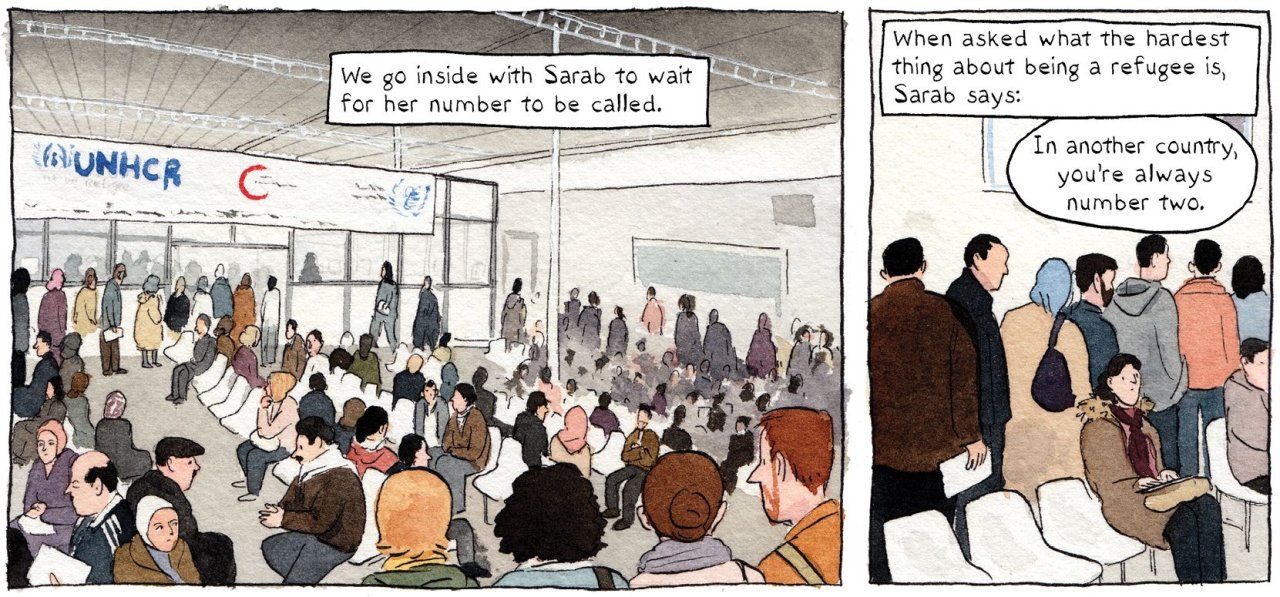

Glidden is part of a growing movement of comics journalists—including Joe Sacco and Susie Cagle—who use illustration not only to comment on events but also to cover them. Comics journalism offers an intimacy and a strong point of view discouraged in traditional newspaper reportage, photography or videography. And drawn images still have power in a world where violent photo-realist images have so saturated daily life that they often no longer shock. When you can watch videos of dead refugees, beheadings and police officers shooting children on demand, sometimes the only way to truly cause alarm is by turning these atrocities into cartoons.

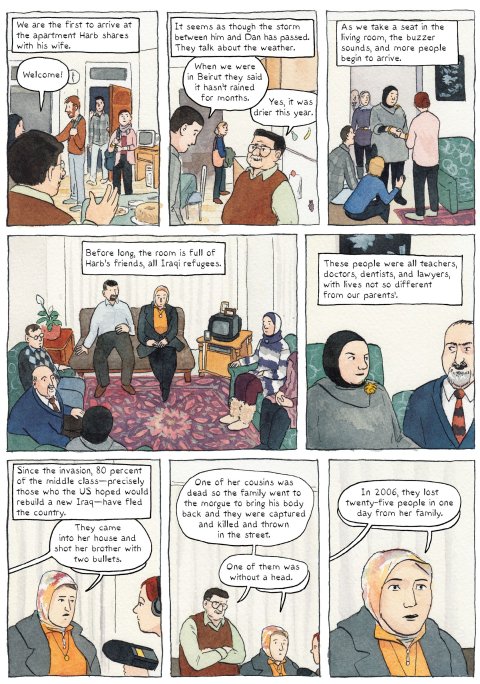

Glidden fills an important void by making foreign conflicts accessible to people who might not subscribe to Foreign Affairs or Washington Monthly. There's a whimsical quality to her watercolor illustrations. Edges are round, and cheeks are rosy. The effect is friendly, welcoming and personal—nothing like the camo-and-sand anonymity in most reporting on the Middle East.

Like How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less, the book is part memoir, part history and part commentary. But Rolling Blackouts is more about journalism than about any specific conflict. In fact, on the very first page, the author asks: "What is journalism?" It's an important question, particularly since the industry is now constantly in crisis.

Glidden sets out on her trip alongside a group of friends who run a freelance journalism collective now known as The Seattle Globalist. Her friends track down stories while she depicts that process through her illustrations. Readers meet Iranian refugees in southern Turkey, Kurds in northern Iraq and Iraqi refugees in Syria. Along the way, we are briefed on the basics of journalism, including how to find and vet sources, how to pitch a story and ethics.

The Demise of Bureaus

But the book also depicts—wittingly or unwittingly—serious structural problems in the way foreign reporting works today, post-bureau. In order to pay for her trip, Glidden raised money through a Kickstarter campaign. While it's great that she met her fundraising goal, this strategy can't spread through the entire industry. And the success of such campaigns is completely reliant upon personal connections and the popularity of a given endeavor.

In the age of the foreign bureau, reporters were paid salaries to live in cities like Istanbul, Baghdad and Rome, where they would spend years—if not decades—building their knowledge about the region and expanding their network of sources. Reporters had the resources and stability to focus their efforts on big projects that were important for the public interest but didn't necessarily turn a profit. During the Vietnam War, news reports from bureaus in Saigon informed Americans of atrocities and played a large role in turning public opinion against the war.

Keeping a permanent staff of salaried reporters and photographers in far-flung cities was always expensive and never particularly profitable. But in the wake of the media industry changes during the early 21st century, it was suicidal. Companies downsized or closed foreign bureaus, replacing or supplementing experienced staff reporters with stringers: plucky freelancers, often just starting their careers, piecing together a living by covering war zones.

The stringer lifestyle can lead to burnout, but it also poses more immediate, tangible risks. Bureaus generally provide fixers and other resources to help keep their regular employees safe. But those may not be provided for stringers. At the extreme end, this can lead to a grisly death, such as that of journalist James Foley, whom the Islamic State militant group (ISIS) beheaded in 2014. Foley was freelancing for GlobalPost and covering the war in Syria at the time of his capture.

Glidden and her friends weren't reporting from active war zones, but one still worries what harm might befall them, for example, when they meet with a Syrian government official about the content of their reportage. Even if, say, their equipment were stolen, Glidden and her friends would have to shoulder the replacement cost.

One quasi-upside of the demise of old journalism is that new genres have flourished in the rubble—like comics journalism. New niche outlets—like The Seattle Globalist, Muftah and Balkanist —can proliferate, at least if they can hit upon a steady revenue stream. But these new endeavors would be even better with reliable institutional support. As the overnight collapse of Al Jazeera America showed, these newcomers don't provide the kind of safe haven that can nourish a decades-long foreign reporting career.

The United States is now in year 25 of a protracted, bloody and expensive series of Middle Eastern conflicts. But unlike in our last major internecine foreign conflict, the Fourth Estate isn't keeping Americans updated on the latest atrocities. That task has fallen largely to independent journalists, like Glidden and her friends at The Seattle Globalist, who can do only so much on their own. Unfortunately, not even a successful Kickstarter campaign can stop an illegal war.