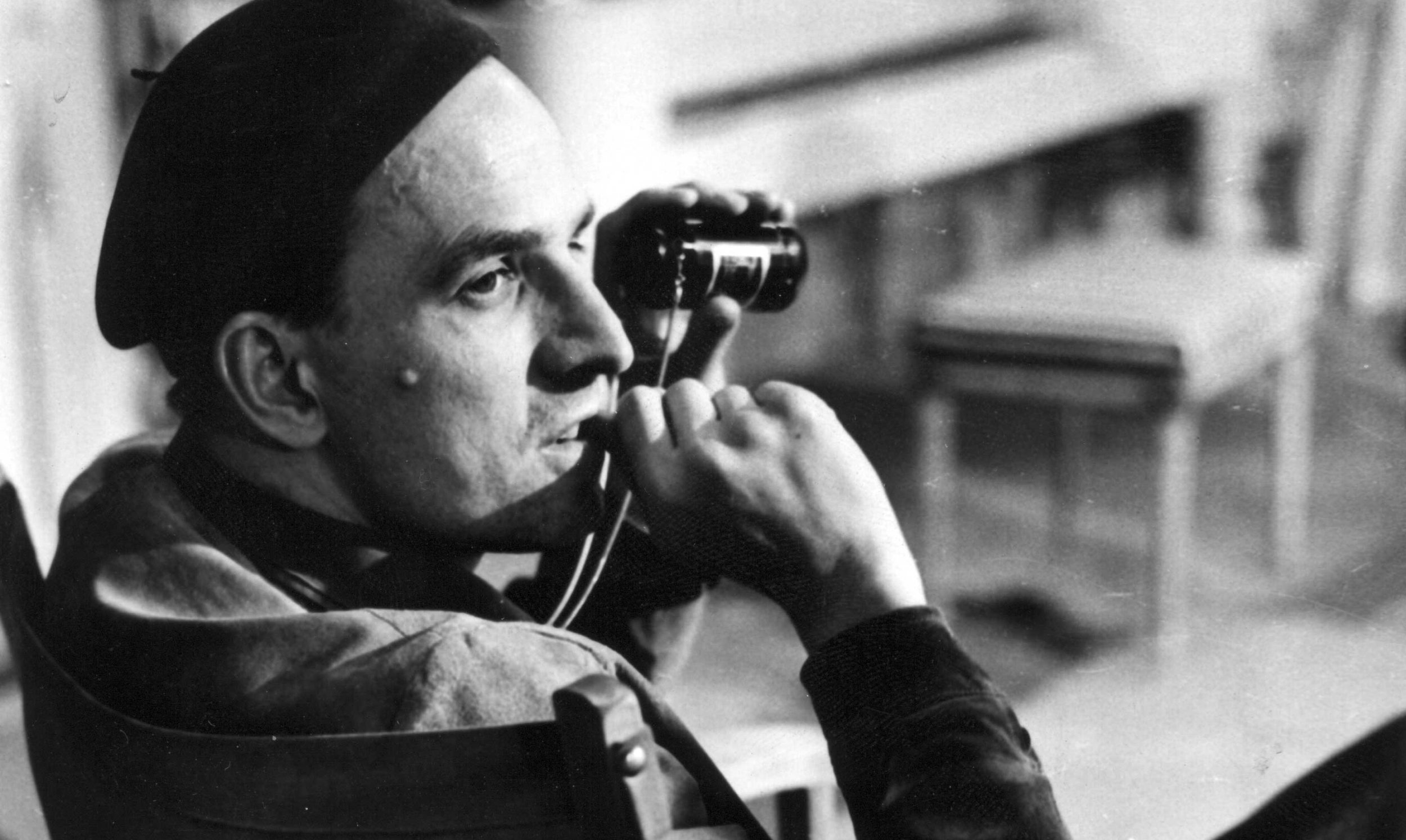

There were times, while watching an Ingmar Bergman movie, when you'd think to yourself, it's like they invented black and white photography just so this man could make films. Bergman and black and white were perfectly complimentary. This was a director who could examine the human condition and see in it innumerable shades—all of them gray. Without slighting his longtime cameraman, Sven Nykvist, it is still possible to say that no filmmaker was ever better than Bergman when it came to finding the right place to put his camera—and no one ever knew better how to wait for the right light for a shot. The results were easily a score or more of movies that were unremittingly painful to watch—indeed, they would have been too painful, had not the way they were shot put one painting-worthy image after another up on the screen. Bergman convinced us that the world was full of ignorance, pain and suffering. But the movies themselves, things of transcendent beauty, easily balanced his bleak view of life. Any reality that could produce films this beautiful—not merely beautiful looking but beautifully written, acted and directed—could not be all bad. Most impressive, this king of the monochrome world could do it all in black and white, could make a world more real than the world we went home to. And then he started making movies in color, and we realized that there really wasn't anything he couldn't do.

The Swedish filmmaker, who died today at 89, grew up with a mother who was alternately and unpredictably charming or brutally cold and a father, a Lutheran minister, who never hesitated to punish his son by caning him or locking him in the closet. We have a fair notion of what life was like in the Bergman household—tense, unhappy, unspoken—because the son would use that experience as raw material in his movies for the rest of his life. Indeed, the older he got, the more he drew on it, right up to his last and most magisterial film, "Fanny and Alexander." (There would, in fact, be several other filmed works for television, and screenplays and theater jobs, but when Bergman bid farewell to major movie making in 1982, he more or less kept his word.)

From an early age, it was the look of things that enchanted young Ingmar. While his father preached, the boy watched the way light poured through the church windows. One of his earliest memories recalled the way sunlight played on a dinner plate and how he could change the way the light fell by manipulating the plate. When he was 9, he traded a bunch of tin soldiers for a magic lantern and began projecting stories on the walls of his home. Then he got his hands on a marionette theater and began single-handedly mounting the plays of August Strindberg. He went off to college ostensibly to study literature, but the worlds of stage and screen had by then possessed him.

It would be nice to say that he could turn his hand to comedy and tragedy with equal facility, and in the sense that Shakespeare could do this, it's true. There are comedies in Bergman's list of credits, and they are cloudlike and sweet and they elicit smiles, but in the Chaplin-Keaton sense, no, they aren't comedies. They're not funny. They're amusing, though, and since they aren't tragedies and since Bergman, unlike Shakespeare, wrote no histories, they must be comedies. Films such as "Smiles of a Summer Night" are at least serene, which is more than you can say for a single minute of one of his darker films, which can leave you feeling like all you want to do is open a vein.

At his best, and face it, his dark films were his best, he could take you on a journey that was painful but somehow redemptive. "The Seventh Seal" is so close to parody that anyone but a genius would have screwed it up. Death is a character, calling people's numbers throughout the film, and given that the film is set in Europe during the Plague, Death is a busy fellow. Black robe, white makeup on the face, plays chess with a knight to decide the fate of a family—stop, I'm laughing already. The thing is, the moment when Death appears on screen, you shrunk back in your seat. Yeah, you say, that's Death all right. I mean, if the credits rolled and they said that the part of Death was played by Death, you wouldn't bat an eye. And boy, this ain't your English teacher's allegory, this is life itself sliced right down to the bone. If he had only made one picture … But that's exactly the point with Bergman: he made a lot of pictures, a lot of them great, some not, but looking back, you'd have to say that the guy just had incredible range. Like Whitman (and believe me this is the only thing he had in common with Whitman), he contained multitudes.

So he wasn't a laugh riot, so what? Just try and find a film that's got more of the range of life in it than "Fanny and Alexander." Show me a film that says more (and with incredibly spare dialogue) about siblings than "Cries and Whispers" (or does more with color). "Scenes From a Marriage" is a lot more than I want to know about marriage, in fact, or at least bad marriage. (Bergman was himself married numerous times and had many affairs, usually with his leading lady of the moment—his private life was as riotous and messy as his films were the work of an artist always in command of his powers.) The funny thing is, his films—the best ones anyway—aren't really about anything. "Wild Strawberries" isn't about old age, although it contains one of the great portraits of old age in all of movie history. An elderly man reflects on his life and comes to terms with what he is—but what we remember are his memories. They become, weirdly, our memories. If I were going to make the argument that film is—like painting and not like fiction—an art not of cognition but of intuition, where emotion and sight (how we feel and how we see, or how the filmmaker makes us feel and see) are paramount, I would cite "Wild Strawberries" as my exhibit A. I have seen this film I don't know how many times, and I can't tell you what it's about—not because it's confusing or because Bergman is confused, but because he is not trying to teach a lesson. He's trying to tell a story. It's a story that somehow tears me apart and restores my soul at the same time. How this happens I have no conscious notion, but knowing what's coming doesn't help: its mystery is never diminished.

Film, Bergman once wrote, is "a language that literally is spoken from soul to soul in expressions that, almost sensuously, escape the restrictive control of the intellect." That's pretty much it.

The trick with watching Bergman, if you haven't seen much, is to keep watching. He made a lot of films, and not all will speak to everyone. You may see three or four that you don't like, only to stumble on a movie that changes your life. There aren't many artists in any field who can do that, even once. Bergman did it again and again. Nobody made movies like his before he came along, and nobody will ever again.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.