Alfonso Cuarón's semi-autobiographical film Roma was so personal to the director that no one, not even his producer, Gabriela Rodríguez, was allowed to read the full script. "I had it because I registered it for copyright," she tells Newsweek, "but he asked us not to read it, and I respected that."

The film, shot in luscious black-and-white, which has earned 10 Oscar nominations, becoming the first Netflix film to score a Best Picture nod. A win could be the third Oscar for Cuarón, who nabbed two for the 2013 film Gravity, starring Sandra Bullock and George Clooney. But Roma's Academy-nominated lead has no Hollywood clout: Yalitza Aparicio is a preschool teacher and a first-time actor of Mixtec heritage. Her character, Cleo, is based on Cuarón's nanny from his childhood in Mexico, where indigenous people make up about 20 percent of the population. Cleo essentially raises a middle-class white family's four children, who represent Cuarón and his siblings, while living a radically different life alongside them. She and her co-worker, Adela, who work from dawn until dark, sleep in a cramped room, forbidden to use electricity at night.

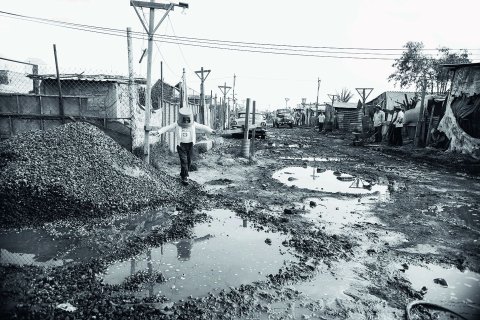

Through Cleo, we see the social and economic injustice woven into Cuarón's story. When she falls pregnant, we learn she has no health insurance. Later, we see the stark contrast between her employer's middle-class neighborhood in Mexico City, the Colonia Roma, and the slums of Nezahualcóyotl City, where Cleo's ex-boyfriend lives. Blink and you'll miss the political posters for then-President Luis Echeverría and Carlos Hank González, Mexico's most powerful businessman and politician at the time.

Most powerfully, we see it in the streets outside the second-floor window of a furniture store, when Cleo witnesses a student protest turn brutally violent. The scene is a recreation of the 1971 Corpus Christi massacre, when the Mexican military slaughtered more than 120 student protesters. The bloodbath was executed in part by Los Halcones, an elite army group that Cleo's ex-boyfriend has joined. The group also attacked students condemning Echeverría's Institutional Revolutionary Party in the infamous 1968 Tlatelolco massacre.

"Social, economic and ethnic discrepancies are present everywhere in the film," says Rodríguez, who has worked with Cuarón for over 14 years. The director "is not trying to shove them down your throat," she adds. "They're just there. You can see them, feel them, pick them up...or not."

Those plugged into more recent Mexican politics will pick up significantly more. In 2014, students intending to commemorate the Tlatelolco massacre clashed with authorities under the leadership of President Enrique Peña Nieto. This time, 25 were wounded, six died and 43 disappeared. The students' whereabouts remain a mystery, angering millions of Mexicans, who have adopted the mantra "Fue el estado," which means "It was the state." Roma debuted on Netflix on December 14, just two weeks after newly elected President Andrés Manuel López Obrador signed a decree commissioning an investigation into the 43 students' disappearance. He had campaigned as the champion of Mexico's disadvantaged groups, like the indigenous communities at the heart of Roma.

In an interview with Variety, Cuarón said the film "was probably my own guilt about social dynamics, class dynamics, racial dynamics. I was a white, middle-class Mexican kid living in this bubble." Famously meticulous, he spent over a year searching for the actress who could play the woman who introduced him to those dynamics, his beloved nanny, Liboria "Libo" Rodríguez. After some 3,000 auditions, he found her in Aparicio, now 25, in the small city of Tlaxiaco in the same region of Oaxaca where his nanny grew up.

Aparicio had no idea who Cuarón was. "Alfonso kindly walked me through the process of making the movie," she says. "He helped me get ready for the most shocking scenes, from the conception of Cleo's stillborn baby to how the character managed to save the kids from drowning." (Aparicio, like all the actors in the film, received only a few pages of the script at a time, before each scene was shot.)

Right away, she connected with her character. "When I see Cleo, I see myself. I'm very attached to children—I'm a schoolteacher, and I love being one—and sometimes I overprotect them." She met with Libo Rodríguez and has said the 74-year-old reminds her of her own mother, also a domestic worker.

Though Gabriela Rodríguez says it was not the film's original intent to highlight the treatment of domestic workers across Mexico and the U.S., she and Cuarón are delighted it has, and they are doing what they can to keep the conversation going. At the Golden Globes in early January, Cuaró brought Ai-jen Poo, the executive director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, as well as several other members of the U.S.-based nonprofit.

"The NDWA has screened Roma for thousands of workers," says Rodríguez. The producer notes that the nonprofit introduced a Domestic Workers Bill of Rights to Congress in November that "would extend workplace protections to 2 million domestic workers." The bill, co-sponsored by Democratic Senator Kamala Harris of California and Democratic Representative Pramila Jayapal of Washington, would be a major breakthrough for domestic workers' rights in the U.S. "If we can give them recognition and acknowledgment for the work that they do, that's fantastic," says Rodríguez of Roma, a film that is also "reaching so many people across Mexico at an important moment politically."

When Cleo goes into labor during the Corpus Christi massacre, she manages to cut the line at a packed hospital thanks to her employers' contacts with health care professionals. Not all domestic workers are so lucky. In December 2017, the Mexican Secretariat of Labor and Social Welfare reported that 98 percent of domestic workers in the country remain uninsured nearly 50 years after the events of the film; they have no access to child care, free medicine or pensions and earn less than $8 per day. A 2015 report from Mexico's National Council to Prevent Discrimination found that 33 percent of 1,243 domestic workers polled reported facing discrimination for being of indigenous descent; 25 percent said their employees barred them from speaking their indigenous language in the workplace.

Under the López Obrador administration, some progress has been made. In December, the Mexican Supreme Court approved the creation of a project that will enroll more than 2 million domestic workers into the social security system and provide access to child care, housing and retirement plans. That same month, the president also pledged to ratify the Convention Concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers; adopted in 2013 by the International Labor Organization, it sets standards such as entitlement to minimum wage and rest hours.

López Obrador has made ethnic representation key since his first day in office. On December 1, he met with representatives from indigenous communities at Mexico City's Zócalo square, where he participated in a traditional rite of purification with herbs and tree resin–based smoke—symbols of the responsibility to govern with hard work and honesty. He is the first Mexican president to do so. "All Mexicans will be assisted," he said in May, "but the poorest and neediest will be given priority. As we know, and even though it pains me to say this, the poorest among the poor are the indigenous communities."

His campaign was filled with such optimistic promises—goals not everyone believes he can deliver: A poll in mid-December from De Las Heras Demotecnia found that only three in 10 Mexicans believe he will be successful. Though the president has vowed to avoid debt and tax hikes in the first three years of his term, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has said Mexico must increase taxes to fund his pledged social programs, which include a plan to construct the Maya Train, an $8 billion project that would connect archeological sites in five southern Mexican states within four years, include the reforestation of more than 2 million acres of land in the states of Chiapas and Tabasco and generate employment for locals and Central Americans. "There are no other parts in the world with such a cultural richness," López Obrador told reporters in November, the BBC reported.

"I truly hope the changes that have been proposed in terms of equality and advancement, especially for indigenous communities, take place," says Aparicio. "However, it takes more than just expressing a desire; it takes concrete actions."

As with minorities in the United States, the indigenous people of Mexico still face deeply entrenched racism. For Aparicio, Roma offers, at the very least, much-needed representation: In December, she was featured on the cover of Vogue Mexico."It is a great accomplishment to see someone like me, whose skin color is darker than the ones we're used to watching in Mexican media, on the cover of a magazine," says Aparicio, who, with her Oscar nomination, is breaking other barriers: She is the first indigenous Mexican actress to be nominated for Best Actress by the Academy, and only the fourth Latina woman to receive the nomination in the Oscars' 91-year history.

Indigenous Mexicans—whose roots extend far beyond European colonization—are rarely portrayed in media, have little influence in politics and often live in poverty. A 2016 BuzzFeed News study found that 15 of the most popular Mexican magazines overwhelmingly featured white-skinned people. Even Roma has faced criticism for offering representation from Cuarón's white, privileged vantage point. New Yorker film critic Richard Brody accused him of "a stereotype that's all too common in movies made by upper-middle-class and intellectual filmmakers about working people...a silent angel whose inability or unwillingness to express herself is held up as a mark of her stoic virtue."

In response, Rodríguez stresses that "there was never any intent to tell a story other than what Alfonso felt was his own, and of this person that he loved. This is how he remembers it, and he's been open about saying that memory is not always accurate."

"The movie has sparked negative and positive comments," concedes Aparicio, "but at least this is a conversation we're finally having—the importance of diverse representation on media."

As for Libo Rodríguez, who worked with Cuarón and Aparicio to create Cleo, there is nothing but support: She loved Roma. "I wasn't there the first time she saw the film with Alfonso," says Gabriela Rodríguez, "but she kept [telling him] she was really worried for the kids in the movie. Alfonso was like, 'It's about you, not the kids.' She's still that person."

When the producer finally did see "Roma" with Libo Rodríguez, at the New York Film Festival, "Libo cried so much. And while Alfonso was walking around the red carpet, she's like, 'Oh, my baby, look at him! I'm so proud.' She still spoils him."