Updated | After her sons didn't return to their father after a visit with their mother last August, police discovered several typed letters while searching Faye Ku's home. One, addressed to a friend and signed by Ku, said to cancel her phone plans and sell or get rid of her belongings, even the jewelry and cash. Another letter was addressed to her ex-husband, David Cook, the father of their boys, Sage and Isaac: "The children and I are safe among friends. Please do not send strangers who can only make life more dangerous for us."

The FBI believes that Ku abducted the two boys when they visited her in Los Angeles. Their father, who lives near Seattle, had custody. With few traces to follow—Ku left behind her credit cards and driver's license and her and the boys' electronic devices—the FBI is picking apart her letters. Indicating the three of them are "among friends" suggests that Ku has help keeping herself and the boys underground, and law enforcement is focusing efforts on parts of the U.S. and abroad where she is believed to have connections.

The boys' father says he thinks "some organization is helping her or just some individuals are helping her."

"God only knows who she's associating with," says Helen Cook, the boys' stepmother.

According to the United States Department of Justice, an estimated 203,900 children were abducted by family members in 1999, the most recent year for which estimates exist. That figure is three and a half times the amount of stranger abductions. In 21 percent of those family abduction cases, the child was gone for a month or longer. Only 28 percent of children were reported to law enforcement as missing.

"Oftentimes, I think people dismiss that as not a serious matter because children are with somebody who ostensibly loves them and cares about them," Ayn Dietrich, a spokeswoman for the FBI's Seattle division, which is overseeing the Cook case, says about family abductions.

The number of family abductions in which an abductor has assistance is elusive, but if Ku does have help, it would place her within an underground movement that for decades has worked to keep missing kids missing.

"Don't look anything like yourself. We'll meet you at the station. Leave everything behind that might remind you of your past life, including pictures and credit cards and your driver's license. Forget who you are."

The network that became known as Children of the Underground once gave these instructions to a runaway mother, People reported in 1989. Family abduction experts widely consider that group and its leader, Faye Yager, as the face of a movement that once helped men and women take their kids into hiding in order to escape partners they alleged were abusive, and whom the courts had granted custody.

Yager formally started helping parents in 1987; in 1992, she told The New York Times that she had helped hide some 2,000 families. Reports have described her network as "a vigilante labyrinth" of "homemakers, ministers and ordinary working people." People magazine called it "the new underground railroad," one that involved nervous pay-phone conversations, Greyhound buses, wigs and pillows stuffed under clothing. Runaways stole names from the birth certificates of deceased people. The network apparently consisted of at least 1,000 safe houses.

An underground had previously existed that helped parents and children go into hiding, but Yager turned it into a movement, says Amy Neustein, a sociologist who knew Yager and who is the co-author of From Madness to Mutiny: Why Mothers Are Running From the Family Courts—and What Can Be Done About It. "Faye's role was to show that the system was so desperate, that it was failing so miserably, there was no choice other than to run," Neustein says. "And Faye's whole purpose was to publicize this."

Neustein says the network consisted of people involved in domestic violence shelters, churches and women's groups. Former nuns would often hide people, as would abuse survivors. "She scrutinized the women very carefully," Neustein says of Yager's potential runaways, to "see who had the mettle, the constitution to run." Yager would only take cases that involved documented abuse, and she helped fathers run too.

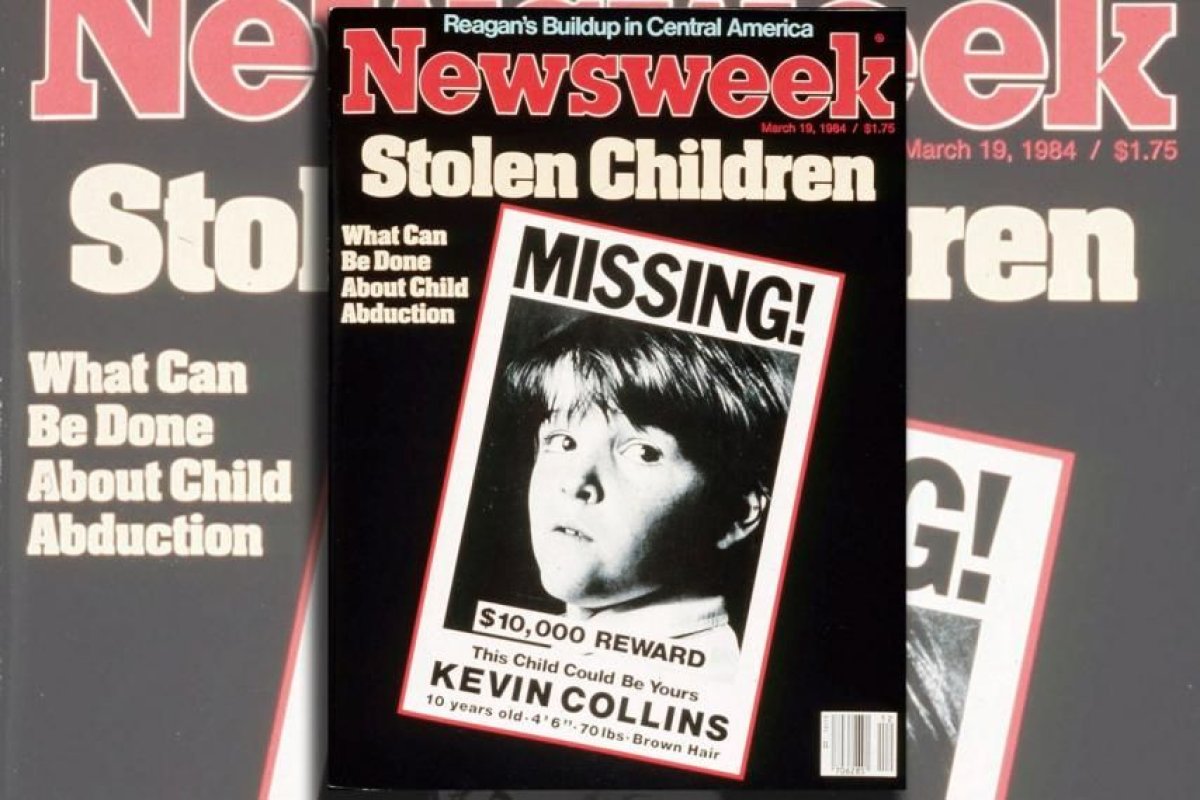

Yager's movement gained momentum at a time when the country was growing increasingly concerned with children and abuse: Congress enacted the Missing Children Act in 1982 and established the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children in 1984; in 1990, the government declared child abuse "a national emergency"; in 1994, Congress enacted the Violence Against Women Act, which gave added protections to victims of domestic violence. In March 1984, Newsweek put child abduction on its cover, writing, "Kidnappings of children are distressingly easy to commit and notoriously difficult to solve."

But by the turn of the millennium, Yager's critics and lawsuits against her from left behind parents were piling up. Parents accused her of kidnapping, interfering with custody and coaching kids into alleging abuse. She once faced 60 years in prison on charges of kidnapping and cruelty to a child. Bipin Shah, a wealthy businessman, appeared on the cover of Time in 1998 when he sued Yager for $100 million for allegedly helping his ex-wife abscond with his daughters. Shah dropped the lawsuit when the girls were found, and soon afterward Yager stepped out of the spotlight. Like the parents she had helped, she seemed to simply disappear.

Yager, whom Time called "a legendary, sharp-tongued Atlanta belle on a holy crusade," now runs a 14-room bed-and-breakfast with her husband in Brevard, North Carolina—population 7,600. A plaque on the 19th-century home, which contains claw-foot bathtubs and antiques, says it is on the National Register of Historic Places. She was first tracked down there last fall by Minnesota's Star Tribune.

Now 68, Yager tells Newsweek that she only retired from the public eye, and that she and her network are just as busy as ever.

"My group still exists," she says in her Southern drawl. "It's much harder," she adds, but she'll still use phony documents and disguises if necessary. "You can still do it, you've just got to have a lot more—I don't want to get into that too much. The FBI just seizes the moment with that, especially where I'm concerned."

Despite being a media fixture decades ago, appearing in countless magazines and on television, Yager says she never sought the attention. "I felt like it cost me my ability to help these children in the way that I thought they really needed help."

So now she keeps her work quiet. The number of people she's "helped," she says, is "probably over 7,000 now."

"And when I say helped, I mean not every single family I'm involved with packs up a bag and runs," she says. "I cherish the calls that I get when the woman calls me before she makes that decision." Of those people, she estimates, "probably about 3,400 people went on the run."

Though her phone no longer rings "off the hook" with calls for her assistance, as she says it once did, she still gets two or three "serious" calls per week. But the network is stronger than ever, with even more safe houses than the estimated 1,000 reported decades ago, she says.

"Listen, there're so many people involved. I wouldn't have any trouble hiding anybody. I could call up, I could send a family to any battered women's shelter or anything in this country, and I assure you, they would disappear and families would hide them. It's that easy. It's very easy," she says.

The digital age has made it harder for parents and their kids to go underground, but technology also makes it easier to find support. Those willing to help are no longer confined to hushed conversations in church basements—they're posting openly online.

Since Sage and Isaac Cook vanished, anti-family-court activists and "protective parents" have taken to the Internet to support Ku. One blogger praised her as a "folk heroine," and others have posted words of support: "Stay hidden"; "Kick patriarchy in the ass"; "Run far and fast"; "If I see them, I will hide them"; "I will aid and abet if need be."

Cindy Dumas, executive director of Safe Kids International and the Women's Coalition, which she describes as social-media-based organizations that aim to alter the family court system, wrote "don't turn this mom in" online about Ku's case. In another post, she wrote: "If you see them do NOT contact authorities!…Good mothers are losing custody in epidemic numbers to controlling and abusive fathers."

Dumas became an advocate after hiding with her sons in the mid-2000s. Unlike members of the "protective parent" movement, which aims to stop family courts from granting custody to abusers, she tells Newsweek that she sees family court injustice as "a civil rights crisis" in which the system is rigged to keep power in the hands of fathers.

That's why Dumas supports Ku—even though not once in the 700 pages of family court testimonies from Ku's custody case does anyone allege that Cook was abusive.

"Mothers who are the primary nurturer of their children should retain primary custody," Dumas says. "That is what is best for the children, that is what's best for the mother, and that is regardless of whether there's abuse. For 200 million years, we have been evolving for females to be the ones to nurture their offspring."

Dumas says she has never directly helped a mother go into hiding, but when women call begging for help, she refers them to people she knows. "It's a very loose movement, and it's very fluid. And that's the only way it can survive."

This underground network has evolved since it made headlines in the 1980s and '90s, she says. "It's just done in a different way. It's done in a smarter way, in a more elusive way. It's like an arms race, you know? They have come up with ways to catch us, and we have to come up with ways to not be caught," she says. Dumas compares the people who hide parents and children to those who hid Jews during the Holocaust.

Neustein, the sociologist, also says that the underground still exists, and that she has heard in recent years from parents who have received help hiding their children. "Now it's much more demure, covert, it's not publicized," she says. "Human nature never changes. So just as many are trying self-remedy when they become disgusted with the courts." Thanks to online groups and postings, she adds, "the validating experience is happening much sooner. They're realizing they're not crazy, that there's a whole movement afoot."

In Minnesota, a case allegedly involving the contemporary underground is underway in which a mother, a couple that owns a ranch and another woman are facing charges of parental alienation for allegedly helping to hide teenage sisters Samantha and Gianna Rucki for two and a half years. One of those facing charges in the case, Dede Evavold, runs a website that criticizes the family court system. She has denied any involvement in a formal network, but has acknowledged that she and the others facing charges all know one another. Lawyers for the ranch owners also deny that the couple is involved in any network. They are scheduled to next appear in court in March.

Robert Lowery Jr., vice president of the missing-children division at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, has acknowledged to Newsweek that the center has "had some experiences" with people or groups that help noncustodial parents hide their kids. "We just want to find the children and make sure they're safe," he has said.

But Child Find of America, another missing-children agency, is hesitant to label who's in the right and who's in the wrong in these situations. "Maybe it is very likely that those groups are the only thing keeping the child who was being abused safe," says program director Shari Doherty. "Unfortunately, sometimes 'safe' isn't legal."

Ku met Cook when they were students at the University of California, Berkeley. They married after they'd graduated, and eventually moved to the Seattle area. He got a job at Microsoft, and she stayed at home or worked occasional odd jobs while they raised their boys. Sage is now 15, and Isaac is 9. The couple separated in 2008 and divorced a year later.

"We realized we were incompatible, we didn't cooperate well, that we fought all the time about trivial things," Cook says. "Her behavior and her views seemed odd to me, but I thought maybe that's how it always was, that couples have to cooperate and have to try to see things from each other's point of view."

Sage and Isaac split time living with both parents until 2012, when Ku decided to allow the boys to live with Cook full-time. On paper, however, they shared custody, and they disagreed about how to raise the children. Ku would later claim in court that Cook was not a nurturing father, in part because he has Asperger's syndrome. He acknowledges that he has been informally diagnosed, but maintains that he is a loving father.

In 2013, Ku told Cook she wanted to take the kids for the summer to Taiwan, where she was born. He agreed, but only if they put the travel plans in writing—an agreement that never materialized. On June 13, 2013, Ku unexpectedly picked up the boys from school and told their nanny and Cook that she was taking them for an overnight visit.

Cook told his lawyer about the unplanned overnight, and the lawyer discovered there were one-way plane tickets to Taiwan booked under the boys' names. So Cook rushed to the airport and informed the police, who arrested Ku before takeoff. Cook got temporary full custody, and Ku was allowed visitation.

A year later, Ku petitioned for custody and testified in family court that she hadn't intended to kidnap the boys, and that she had thought that Cook had agreed to the trip. Cook told the court that he was worried that if he sent the boys to L.A. to visit her, she would take them.

One year later, Cook's fear was realized.

Ku had a vast Internet presence, and Cook thinks it's possible that people she met online are helping her hide. Additionally, Ku's son Zephyr, a toddler, who has a different father, is also considered missing. There are multiple websites registered in her name, and she appears to have posted in various online forums, frequently with the pseudonym "littlefaith."

In 2014, she wrote in a series of cryptic Facebook status updates, "I'm a standard deviation away from every kind of normal that you can think of.… I AM THE EXCEPTION TO YOUR RULE." In 2015, months before disappearing, she wrote, "The problem is I am not in the box, and the people in the box can't see the box."

Ku even commented on a post about a family court awarding custody to an alleged abuser, just two weeks before her disappearance, expressing wariness at first ("How do we know what is really happening in this case?"), but then writing: "I'm against our current system of having police involved in families, even in cases of molestation or physical abuse. It only increases the danger and tragedy for everyone."

Newsweek's attempts to contact Ku were unsuccessful. The lawyer who represented her in the custody case, Terry Zundel, says Ku was appealing for custody and likely representing herself at the time she went missing.

Dietrich, the FBI spokeswoman, says the agency is monitoring the online support for Ku and that such postings help "drive another set of leads. It means there's other people that we want to talk to, people that might be connected with that movement or people who are familiar with how those work."

One friend, Maureen Sklaroff, says, "She's very nice and very caring about other people. Very smart." Other friends offered similar testimony in family court.

But the father of Ku's son Zephyr says that "she's narcissistic and doesn't believe fathers have intrinsic rights.… She is a loving mother but sociopathically selfish when it comes to co-parenting." He says she did not let him have a relationship with his son. He asked that Newsweek not print his name because he did not want it associated with the missing-children case.

"She definitely questions every societal norm," Sklaroff says. Ku posted on Facebook about being against vaccines and "government control," and intensely advocated for homeschooling.

One place where law enforcement believes Ku and the boys may be is her native Taiwan, which does not belong to the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, an agreement among 93 contracting states to aid in the return of abducted children.

Following the recent deadly earthquake in southern Taiwan, Sklaroff posted on Facebook, tagging her friend Ku: "If you happen to be where there was an earthquake recently, I hope you all are okay. It sounds like the worst damage was not near where you might happen to have been, if you were somewhere that had an earthquake."

But with the Cooks and the FBI poring over posts like that one, it's possible that she may have only been trying to confuse things further.

"I think they're afraid to be found," Cook says of the boys. "They wouldn't go away and intentionally not see us anymore, but I think they believe they're in a situation where they have to choose."

Several hours after Newsweek published this article, the FBI announced that authorities had located Sage and Isaac Cook in the state of Sinaola, Mexico and that they had reunited with their father and returned to Washington state. Faye Ku has been deported to the United States and is scheduled to appear in court on February 16 on charges of international parental kidnapping, the FBI said.

Correction: This article previously incorrectly stated the year in which Bipin Shah appeared on the cover of Time; it was 1998, not 1999. This article also incorrectly stated that 72 countries belong to the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction. The number is 93.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Max Kutner is a senior writer at Newsweek, where he covers politics and general interest news. He specializes in stories ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.