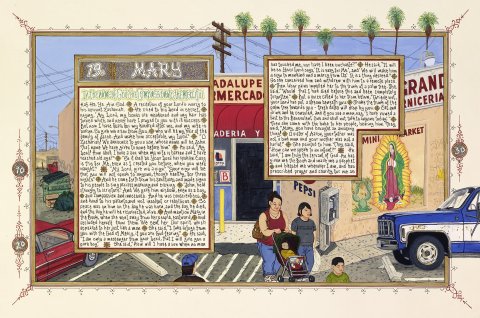

It is audacious for any artist to treat as his subject the sacred texts of a faith to which he does not subscribe. It is especially so if you're an atheistic Southern California surfer who decided he would create an illustrated version of the Koran, despite the long-standing Islamic tradition of not depicting the human form. But that is precisely what Sandow Birk set out to do. And did. His American Qur'an, recently published, is an unbeliever's tribute to the message of Muhammad.

A few years ago, it occurred to Birk—who lives in Long Beach, California—that Americans knew very little about Islam, even while many of his countrymen bore so much enmity toward it. His search for the perfect break had taken him to Muslim countries like Indonesia and Morocco, and left him with the awareness that Islam wasn't the religion depicted on Fox News. He knew he wanted to say so with his art, but he didn't know how. Then came a 2004 surfing excursion to Ireland and, while there, a visit to the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin, where a number of illustrated Korans were on exhibit. There, in a Catholic country, Birk realized what his Islamic project would be.

Published this fall after nine years of toil, The American Qur'an is Birk's take on what he calls "the most important book in the world" in the past two decades. Though he readily concedes that he is "not an Islamic scholar," Birk worked from nearly a dozen translations of the Koran, transcribing each of its 114 suras, or chapters, by hand. The text is in English, the font borrowed from both Islamic tradition and the famed graffiti culture of Los Angeles. Each page is illustrated with a scene from modern American life, fusing the words of Muhammad with contemporary tropes in a way that is unique and transgressive, especially considering the aniconism that marks Islamic art (Birk never depicts Muhammad in the book).

"I got sick of people telling me what Islam was," Birk said one recent afternoon during a presentation at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. In front of me sat several fashionable blondes, including Birk's gallerist. Next to me were several women in the hijab, listening as Birk—who looks well-kept and healthful, more Los Angeles than La Bohème—spoke about their faith. Worlds were colliding, in the famous words of George Costanza. But in a good way.

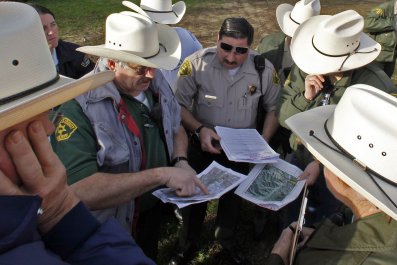

Birk says he studiously avoided Islamic scholarship while working on his American Qur'an. "I'm in the wilderness, and I receive this vision," he told me over a beer after his museum talk. And wherever the vision took him, he went. For example, for the sura concerning Noah's Ark, he drew a scene of Hurricane Katrina; another page shows the Oklahoma City bombing; yet another (Sura 44: "Smoke") has the World Trade Center aflame on 9/11. But there are everyday scenes too, of ordinary Americans, Muslim and not, going about their works and days. For example, a sura on the Resurrection shows a busy operating room; part of the story of Joseph shows an immigration raid near the Mexican border.

Birk says he wanted to create a "Pan-American book" that represents all 50 states. So there are images of the Upper Big Branch mine explosion in West Virginia (Sura 18: "The Cave") and of religious Jews in New York City (Sura 45: "Kneeling"). There's even a NASCAR-style race. This is a holy book that is very much lowercase-c catholic, challenging the notion of Islam as a foreign, inscrutable faith.

Most of Birk's work has focused on wars both foreign and domestic, real and imagined. In Smog and Thunder: The Great War of the Californias (2000) was an installation "depicting an imaginary war between San Francisco and Los Angeles," with paintings, maps and even a 45-minute mockumentary. The relentlessly referential Birk created war posters that harked back to patriotic World War II imagery ("Bomb the Bay!"); one painting is an obvious reference to Jacques-Louis David's Intervention of the Sabine Women, thus tying the fate of California to that of ancient Rome.

Birk can be accused of an algorithmic approach to art: the depredations of American life today filtered through the tropes of yesteryear, with his draftsmanship leaning on the vocabulary of painters past. Reviewing a show of his in 2002, New York Times art critic Ken Johnson warned that Birk "risks imprisonment by his own conceptual formula." This critique ignores the fact that the formula is extremely effective and its results immensely pleasing to behold. In 2001, for example, Birk exhibited a series called Incarcerated: Visions of California in the 21st Century, for which he painted all 33 of the state's prisons. The faux-bucolic paintings recall the dramatic landscapes of 19th-century naturalists like Albert Bierstadt, except the eye inevitably drifts away from fields and streams toward the barbed wire and guard towers of the Pelican Bay State Prison or the California Institution for Women. The point is obvious, but the paintings are too pretty to be preachy. (He subsequently executed a project on the prisons of New York, which was the subject of Johnson's tepid review.)

Birk was disgusted by the presidency of George W. Bush and its forays into Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2007, he exhibited The Depravities of War, 15 woodcuts he created at a studio in Hawaii. Recalling The Miseries of War by Jacques Callot and The Disasters of War by Francisco de Goya, the woodcuts depict the burning oilfields of Iraq, the humiliation of prisoners at Abu Ghraib and injured American veterans waiting for help outside a medical center.

"It would be fittingly ironic to say that more planning went into this project than into the invasion it chronicles," Birk wrote, "but it was actually equally spontaneous."

During his San Francisco presentation, Birk showed a photograph of an exhibition of several of his suras from The American Qur'an at the PPOW Gallery in Manhattan. In the image, a group of Muslims have genuflected, praying on the gallery floor, a show of faith that also, more subtly, has turned into performance art.

Not that Birk has any self-serious illusions about his work, which is art about religion, not religious art. For example, he had his wife, Elyse Pignolet, a ceramic artist, fashion a mihrab, or prayer niche, in the shape of an ATM, thus honoring the notion of faith while subverting it. If this art is blasphemous, it is respectfully so. As Islamic scholar Zareena Grewal says in her introductory essay to The American Qur'an, "Birk's aesthetic sensibilities are simply too weird and too different" from that of many Muslims "for them to enjoy his work." Grewal wrote that reading The American Qur'an "is a thought-provoking and enjoyable experience, but not exactly a religious one."

When Birk first started to exhibit completed suras in 2009, some Muslims were skeptical, with a spokesman for a Los Angeles mosque telling The New York Times, apparently without having seen the work, that Birk was "misrepresenting the Koran." Birk says that such concerns quickly subsided and that he's received many thanks from American Muslims, who have felt maligned as Donald Trump and Ted Cruz compete to out-demagogue each other. In The American Qur'an , Birk says, these modern adherents of Islam find affirmation and inspiration, a surprising and welcome guidepost for their faith.

After his presentation at the Asian Art Museum, Birk stayed behind to sign copies of The American Qur'an. Later, he and I walked to the SFJAZZ Center, where he and Pignolet created three murals paying homage to the history of jazz, with its sorrowful themes of oppression, migration and homeward longing. The experience of black Americans escaping the Jim Crow South was far from Birk's own. But that wasn't going to stop him.