Scientists have found that one of Saturn's moons might be harboring an ocean of water beneath its icy surface.

Mimas, which is Saturn's 7th largest moon and resembles the Death Star from Star Wars, has a unique orbit around its parent planet that can best be explained by the presence of a liquid ocean beneath its 15 to 18-mile-thick, cratered, icy crust, according to a new paper in the journal Nature.

This ocean is thought to be fairly young on a cosmic timescale and only got close to the moon's surface in the last few million years.

"The key results are 1) the data show that Mimas has a subsurface ocean right now and 2) the ocean cannot be very old, at least in geologic terms. While the new study cannot totally confirm an ocean, it certainly strengthens the case for one. The ocean is liquid water (perhaps salty). It is tens of kilometers deep (something like [40 miles] total) under an ice shell that is [12-18 miles] thick," Alyssa Rose Rhoden, an astronomer at the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado, told Newsweek.

Data gathered by NASA's Cassini probe revealed that Mimas had some strange qualities in its rotation and orbit, which have long been theorized to be explained by the moon having either an elongated rocky core or a secret ocean under its surface.

"Mimas's moments of inertia were previously probed by looking at rocking motions, known as librations, that the moon makes as it is tugged by Saturn's gravity. These measurements revealed that Mimas's librations are much larger than would be expected from the shape of its surface," Matija Ćuk and Rhoden wrote in an accompanying Nature News & Views article. Ćuk is an astronomer at the SETI Institute in California.

"This could be explained either by the moon having a very elongated rocky core, which would enhance the difference between its moments of inertia, or an internal ocean, which would allow its outer shell to oscillate independently of its core," they wrote.

"Because there was no other widely recognized evidence for an ocean, many planetary scientists preferred the elongated-core hypothesis. But the once-neglected — and just as plausible — ocean option now has support from another corner."

The Cassini data shows that Mimas precesses backward in its orbit, which must result from the elongation of its gravitational field. This new paper reveals that the rocky-core model doesn't fit observations of the moon's rotational motion, meaning that the ocean explanation is much more likely to be true.

"The big surprise is that, if Mimas is assumed to be frozen, the moments of inertia calculated from its librations do not match those required to explain its orbital precession. In fact, Lainey et al. [the authors of the paper] showed that no internal distribution of mass in a solid body can explain these two data sets. The only viable conclusion is that Mimas has a subsurface ocean," Ćuk and Rhoden said.

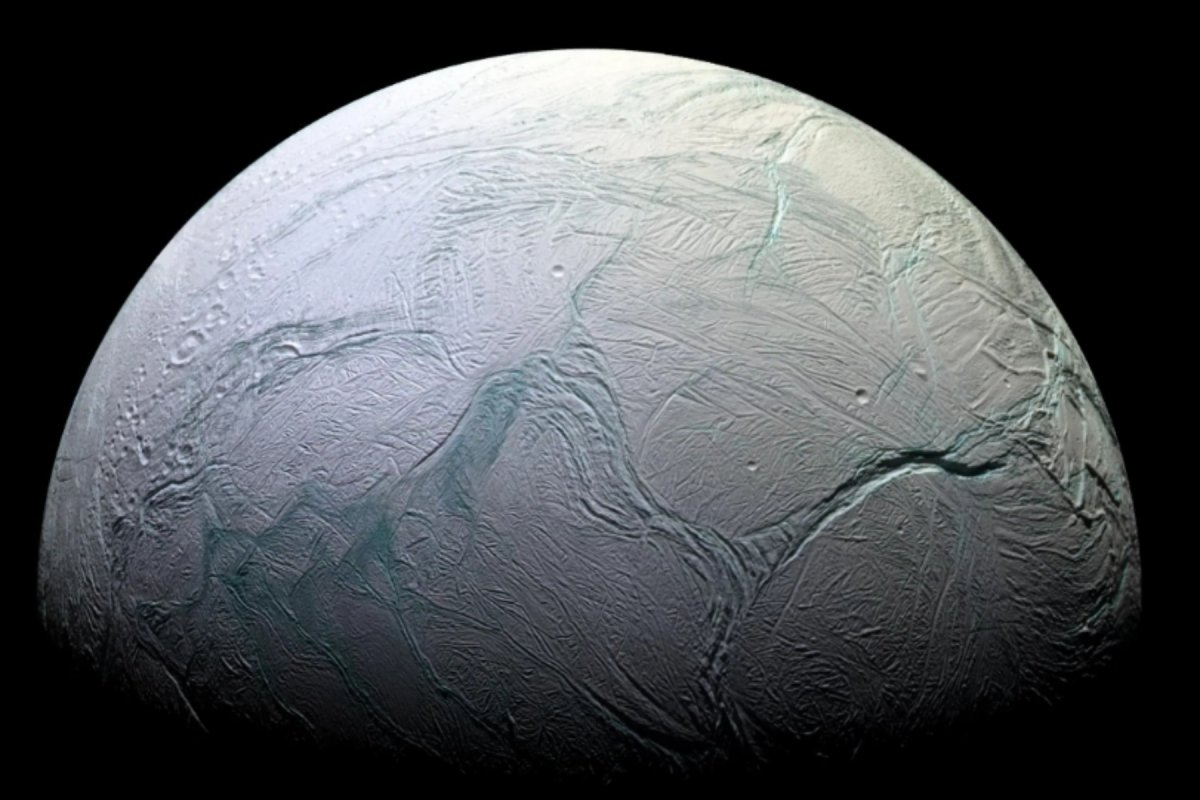

Mimas having a hidden subsurface ocean makes it much more similar to its neighboring moon, Enceladus, which often sees huge plumes of water bursting from its icy surface.

Unlike Enceladus, which has heavy fracturing on its icy surface, Mimas's surface gives away no clues that an ocean is lurking beneath it. This may be explained by the ocean being relatively new to the moon.

"A young ocean also matches constraints derived from Mimas's geology; in particular, the large crater, known as Herschel, could not have formed in an ice shell that is as thin as Lainey and colleagues (and others) predict. Rather, the ice shell must have thinned by tens of kilometers since Herschel formed," Ćuk and Rhoden said.

The presence of an ocean on Mimas may also provide clues to the formation of Saturn's moons and imply that other icy worlds could have oceans hidden deep beneath the surface that we don't know anything about.

"The moons for which we have the best evidence of present-day sub-surface oceans are Europa (at Jupiter) and Enceladus (at Saturn). I believe there is also strong evidence of deep oceans within Ganymede and Titan.

"Other candidates for present-day ocean moons include Callisto, Triton, and Dione, whereas moons like Tethys, Rhea, and Charon may have had oceans in the past that froze out.

"The moons of Uranus hint at geologic activity that could be enhanced by an ocean, but we really have too little data right now to draw strong conclusions. Europa and Enceladus tend to get the most attention in terms of astrobiology," Rhoden said.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about Saturn's moons? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Update 2/15/2024 13:18 p.m. ET: This article was updated with comment from Alyssa Rose Rhoden.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.