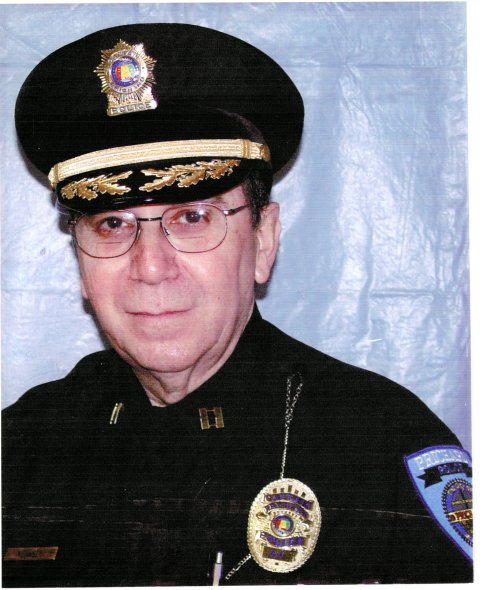

It was October 2011, and Captain Charles Kennedy, a veteran policeman, was in the main office at the Restoration Youth Academy (RYA), a Christian home for troubled teens in Prichard, Alabama, when he caught a glimpse of something shocking on a close-circuit monitor: a naked boy crouching in a 6-by-8-foot isolation room as a light bulb burned overhead.

Kennedy had been waiting for William Knott, the program's manager, to return with some paperwork, and when he walked back into the office, Kennedy asked about the boy, whose name he later learned was Robert. He wanted to know what the boy had done to deserve such treatment. Knott, a squat, powerfully built ex-sailor, calmly explained his rationale: "He's got an attitude. He's only been there for a day, and he'll be there for another day or two."

"Can't you give him some clothes?" Kennedy asked.

But Knott offered only a vague answer.

Kennedy had been investigating RYA for little more than a week, spurred by a few complaints by parents of kids in the program. RYA's executives had promised parents "hope for their teenagers' future, when hope doesn't seem possible," as its website declared. And many were grateful for that. "I was scared I would find my son hanging from a rope or dead from a needle," says Leslie Crawford, from South Portland, Maine, who paid $1,500 a month to send her truant, drug-using son to RYA.

But what Kennedy had found behind the school's forbidding metal gates disturbed him. He'd come after hearing from two mothers who were alarmed that their kids had been facing severe punishment. Knott had provided a tour of an empty classroom inside interconnected mobile homes and an adjoining cafeteria filled with quiet, unsmiling children. Afterward, he had allowed Kennedy to speak alone with one of the boys whose mother had called him.

That's when he learned firsthand about the teenagers' accusations of abuse. As he investigated, he found that many of the school's "cadets" were afraid to talk. But those who did left Kennedy with the impression that he had stumbled across something terrible. The boys, for instance, told him they were often grabbed out their beds in the middle of the night and forced to fight one another until one was beaten to a pulp. All of them were subjected to a brutal, daily regimen of exercises, sometimes stark naked—pushups, jumping jacks and running in place. Drill instructors, including Knott, frequently punched them, choked them and body-slammed them as they worked out. On his first day in the program, one boy claimed, Knott crouched down next to him, and, after yanking his head up by his hair, started pounding his skull against the floor while shouting, "You will exercise until I get tired!" Another told Kennedy he had been held upside down in shackles and hit with a belt, an allegation later supported by an eyewitness letter by another teen. (Newsweek has either provided anonymity to the minors in the program or changed their names to protect their privacy.)

Kennedy wanted to protect the cadets from abuse, but he also knew he lacked the hard evidence needed to make an arrest. So for the next week or so, he periodically returned to RYA, which is how he found himself with Knott, asking about the naked boy named Robert in the isolation room.

The officer was concerned. The United Nations considers the use of solitary confinement as punishment to be torture. But the police officer knew what he'd just seen wasn't illegal in Alabama if it took place over a relatively short time span. He also knew these institutions bar the young people they control from unmonitored communication with family and outsiders—and most states, including Alabama, don't even protect workers who report child abuse from being fired. The result: Abuse isn't reported until long after it was committed, which makes prosecutions nearly impossible.

As Kennedy continued checking on Robert, the boy eventually told him about his stay in isolation. Knott and the school's founder, John David Young Jr., the pastor of Solid Rock Ministries in Mobile, were frustrated by Robert's "poor" attitude and persistent depression while in solitary confinement; and they were determined to change his behavior. So after days in solitary confinement, they dragged him from the isolation room to Knott's bedroom, where Knott handed the boy a .380 automatic pistol. "If you're so determined to kill yourself," Knott said, "you should put the gun next to your head and pull the trigger."

"I pulled it, and it went click," Robert told the officer.

Kennedy was appalled. He immediately confronted Knott and Young about this sadistic bit of theater, but they didn't deny the boy's accusation. In fact, Knott went to his nearby bedroom and returned with the gun and placed it Kennedy's hand. "I was just teaching him a lesson," he said.

"I knew then I was dealing with crazy people," says Kennedy. "You don't do that to a human being."

But the insanity had only begun.

Whippings, Beatings and Alleged Rapes

Today, in the United States, there is a multibillion-dollar industry for residential treatment—one that sells an illusory promise to desperate parents: Your children's addictions and mental health problems can be cured with a relatively quick (and usually expensive) fix. Yet the potential danger of abuse and neglect is a real threat for many of the 200,000 to 400,000 young people trapped in the nation's poorly monitored secular and religious "group care" facilities, "troubled teen" residential schools and unlicensed treatment programs. Too often, critics say, these programs profit off the misery of emotionally troubled kids, substance abusers or just misbehaving youth, as well as their parents, who struggle to deal with kids they can't control. "These are throwaway children," says Jodi Hobbs, the president of the nonprofit group, Survivors of Institutional Abuse. "They are looked at as dollar signs, not as individuals."

One of the most common types of private programs for errant youths are the virtually unregulated religious schools, many of which push fundamentalist Christian beliefs and employ violently harsh discipline against enrollees. Inspired in part by the programs of a fiery Baptist radio preacher, the late Lester Roloff, purveyors of these programs have been exposed for whippings and beatings and accused of rape. Perhaps the largest alliance of such ultraconservative churches is the far-flung Independent Fundamental Baptist organization with thousands of churches nationwide and numerous boarding schools that cite the biblical importance of breaking the will of the child. "If you're not bruising your child," a pastor declared in a 2007 sermon captured by ABC News's 20/20, "you're not spanking your child enough."

Related: For decades, child abuse was allegedly covered up in Brooklyn's Hasidic community

The template for these schools is Roloff's Rebekah Home for Girls in Corpus Christi, Texas, which he created in the 1960s and that became the centerpiece of a chain of religious reformatories. Roloff's program involved vicious corporal punishment and locking kids in isolation rooms where his sermons were played endlessly. Over more than two decades, the controversial preacher was arrested a few times and his Rebekah school relocated to various states in part to sidestep any state laws mandating oversight, such as one in Texas requiring inspection of all child-care facilities. Yet Roloff faced few consequences, even though one lawsuit featured affidavits from 16 girls saying they were whipped with leather straps, severely paddled and handcuffed to pipes. "Better a pink bottom than a black soul," Roloff famously declared at a 1973 court hearing.

The stern spirit of Lester Roloff lives on in the resistance by church leaders—often abetted by local politicians—to any government oversight under the guise of separation of church and state. Nine states, including Florida, Alabama and Missouri, have wide-ranging "faith-based" exemptions protecting various church programs and schools from direct government oversight (while 26 states have no requirements for any private schools, religious or secular). Regulations in the U.S. are so loose that controversial organizations are rarely sanctioned despite allegations of rampant abuse. Some programs such as Teen Challenge, the world's largest fundamentalist treatment chain for adults and youth, are often subsidized by taxpayer dollars—despite many public accusations of abuse and neglect. (Over the years, Teen Challenge has denied any wrongdoing or misconduct.)

As Kennedy says of the nation's unmonitored religious programs: "They're hiding behind a cross, but there's for damn sure evil going on."

'I Was in Shock'

After he spoke to Robert, Kennedy knew he had to move quickly. So in early 2011, he returned to RYA for a final round of confidential onsite interviews. Arriving after dinner, Kennedy thought he'd be allowed to speak to the boys privately in Knott's office. Instead, the RYA manager led him to the shower area where Knott told Kennedy he could interview the boys. To the officer's surprise and discomfort, each boy entered and sat across from him completely naked to answer his questions, while Knott stood nearby to watch.

Kennedy was suspicious, but only later did he learn the full purpose of the stunt; as an RYA cadet, William Vargas, explained in a letter to the officer: "After Captain Kennedy left, Mr. Will [Knott] told everyone to write a paper saying that Captain Kennedy wanted to see us naked, and make Captain Kennedy look like a pedophile."

Kennedy conducted his final interviews, then went to his chief, Jimmy Gardner, who gave him permission to present his findings to the Mobile County District Attorney, Ashley Rich and her chief investigator, Mike Morgan. But from the beginning, Kennedy sensed something was awry.

So when the chief gave Rich and Morgan a briefcase with documents from the case one day in the fall of 2011, Kennedy stopped him, and asked to make sure everything was inside. What he discovered left him even more jaded: Half of the documents were missing. Kennedy went down to his car, and retrieved copies of everything intended for Rich, then briefed her and Morgan on what was going on—the forced fighting, the isolation cells and shackles, the beatings of naked boys. After Kennedy made his presentation, he says Rich coolly responded: "Parents need to be more careful where they send their children."

"I was in shock," Kennedy says. Morgan, speaking for the district attorney's office, doesn't recall Rich making such a statement.

Rich sent Morgan to RYA to investigate; there, he insists, he conducted confidential interviews. But Kennedy says some of the boys told him Morgan mostly talked to them when Knott was around or were too petrified to speak honestly. Kennedy's hunch was right; the district attorney took no further action.

The officer isn't the only one who felt like Morgan and Rich should have done more. Karin Bazor, a former instructor for the RYA girls who quit in disgust in 2012, says she later went to Morgan with evidence about abuses at the facility, "He looked at me like I was crazy and said it's impossible to prosecute someone [whose program is] under a church covering." Morgan declined to answer questions about this accusation.

Giving up hope that local law enforcement would handle the problem, Kennedy next turned to local Child Protective Services and its director, Beth Nelson. In a meeting with her on November 21, 2011, he says he laid out all he knew—the documents backing up the allegations of abuse and a long, detailed list of witnesses to contact. Nelson, in turn, agreed to visit RYA. However, Kennedy says she gave the facility's leaders two-days' advance notice of her investigation. She found no signs of abuse, and two subsequent Department of Human Resources (DHR) investigations didn't either.

Better a pink bottom than a black soul.

Even so, after Nelson conferred with Alabama's DHR Commissioner Nancy Bruckner and Morgan, they reached an initial decision to close down Restoration Youth Academy on November 28—apparently based on Kennedy's concerns, even though they didn't substantiate them. Yet the two changed their minds after talking to Young and Knott the next day; they didn't want to face the cost, liability and logistical hassles of removing nearly 50 endangered kids, according to Kennedy. (Local and state DHR officials declined to comment on any aspect of their RYA investigation. I was unable to reach Nelson for comment.)

Kennedy was infuriated, and called Nelson to protest. To no avail. "There is more concern about chickens on a poultry farm in Alabama than for children!" he says.

'Their Parents Don't Vote Here'

But Kennedy didn't give up. He started writing detailed letters to Alabama Attorney General Luther Strange and other state officials outlining the rampant abuse at RYA. All the while, he was adding new victims to his list of people to contact.

Yet his efforts mostly led to more of the same. Early in 2012, Kennedy says the attorney general's chief investigator, Tim Fuhrman, brushed him off after he'd done an on-site investigation that didn't confirm Kennedy's claims. Fuhrman apparently didn't try to contact many of RYA's former cadets or their families who were willing to speak about the program's horrors, a point confirmed by some of the victims. "Nobody ever called me or cared, except Captain Kennedy," says one parent.

On February 3, 2012, Kennedy says he got a call from Fuhrman, who told him the attorney general had determined the case wasn't worth pursuing. "These children are from out of state and their parents don't vote here and I don't want the churches mad at me," Kennedy says Fuhrman told him in regards to Strange's views.

In a letter, Strange denied making such a statement, speaking for himself and his office: "The quote attributed to me via Chief Investigator Fuhrman is not true. A potential victim's residency has no impact on our investigation actions. The record of prosecution by this office clearly demonstrates a strong stance against the abuse of any child. The allegation that my office did a 'superficial job' is unsupported and unfounded."

Frustrated, Kennedy turned to the local newspaper, the Mobile Press-Register, as a confidential source. In March 2012, a story appeared about "questions" regarding RYA, but it focused, in the top section of the article, only on the lack of licensing for the program and its counselor, Aleshia Moffett. The article mentioned in a vague way the "rough treatment" cited by one of the victims. After that story appeared, the issue faded amid the drastic layoffs at the state's major newspapers of two-thirds of their editorial staff.

For the next two years, even after he retired from the force, Kennedy continued writing letters, trying to get Alabama authorities to stop the abuse. But state officials continued to ignore his pleas.

'They All Knew'

In March 2015, Kennedy was about a year into his retirement and working on developing a disability rights lawsuit against RYA, which Young shuttered and had since started a facility in Mobile under the name the Saving Youth Foundation in order to avoid a recent spate of negative attention.

He was rushing to keep an appointment with the lawyer, when he drove past the ramshackle boys' home. Yellow crime scene tape and police cars surrounded the facility, and Kennedy's heart sank. "I thought for sure someone had been murdered," he says.

After his meeting, the former officer wheeled around and headed back to the facility, fearing the worst. When he pulled up next to the building, he saw John Barber, a Mobile Police Department captain, and his face looked deathly pale.

"What's happened?" Kennedy asked. "Have they killed somebody?"

"No, but I can't believe they haven't," Barber said.

A veteran of more than two decades of police work, Barber began recounting the scenes of horror inside—the isolation cells, the shackles, the frightened children—the same awful conditions Kennedy had been warning officials about for years.

If you're so determined to kill yourself, you should put the gun next to your head and pull the trigger.

Barber's department had learned of these horrors from a mother who lived out of state and had picked up her daughter from the facility's girl's program in Mobile. Horrified about what she saw there, she took photos of the isolation rooms on her cell, then called the police in Mobile. In March 2015, the detective on the case, Sergeant Joe Cotner, referred the complaint to the local DHR for a child abuse investigation, and the new team there—Nelson had retired—took the allegations seriously. A DHR-led raid a few days later rescued 36 children.

As he stood outside, talking to Barber, Kennedy sensed a real opportunity to finally win some measure of justice for abused children. A few days later, the now-retired police captain began briefing Cotner on the case, handing him all the files he'd been keeping in the trunk of his car.

Finally, after four years of trying to stop Knott and Young, he had an ally in law enforcement.

'Did You Hear About the Verdict?'

After the March raid, the Mobile police and DHR shut down the Saving Youth Foundation, and with Kennedy's assistance, the police arrested Knott and Young along with Moffett, the counselor, on charges of felony child abuse several months later.

The trial began in January 2017, and Kennedy anxiously attended all four days of the proceedings. But as a potential witness, he couldn't sit inside the courtroom and instead relied on a cousin, among others, to brief him on what was happening.

On the final day, when the jury left to begin deliberations, the fatigued crusader drove home for a break. It was 5 p.m., and he was sitting on his front porch, when he got an urgent call from Leslie Crawford, the mother in Maine who had also long fought for Alabama law-enforcement to crack down on RYA.

"Did you hear about the verdict?" she asked him excitedly.

It had only been two hours since the jury left, and Kennedy couldn't believe what he was hearing. The jury, she explained, had convicted Knott, Young and Moffett on all counts of aggravated child abuse, the maximum charge. Kennedy was ecstatic. He asked her to repeat the verdict again to make sure he'd heard correctly. Not only had he been personally vindicated, but the people he'd been fighting against were finally going to prison.

As he put it in an email to friends and supporters: "All of the monsters were convicted!"

'The Blood of Children'

On February 22, Kennedy felt a similar sense of elation when a Mobile judge sentenced Knott, Young and Moffett each to 20 years in prison. But his feeling of triumph and vindication is tempered by the fact they got away with it for so long. "They all knew," he says of the government agencies that ignored his pleas, "and they did nothing."

It's a pattern that continues to this day. Neither the long prison sentences nor the shuttering of the brutal facility have fundamentally changed oversight of such programs in Alabama—or anywhere in the country. Over the past 20 years, the Mobile effort against Knott, Young and Moffett remains one of a handful of arrests and prosecutions for physical abuse allegations at any youth treatment facility in the country. Other unmonitored religious and secular troubled teen facilities in Alabama and elsewhere continue to operate with impunity, generally protected by the indifference of local and state police, prosecutors and child protection agencies. "We've received thousands of police reports," but relatively few have led to prosecutions, says Angela Smith, the founder and national coordinator of the Seattle-based Human Earth Animal Liberation advocacy group, better known as HEAL.

Now 73, Kennedy is trying to close other facilities. Most recently, he's briefed the district attorney's office in Baldwin County Alabama about troubling abuse allegations at a facility in rural Seminole called Blessed Hope Boys Academy, which is run by pastor Gary Wiggins. In September 2015, a gay teenager who had been imprisoned at RYA before the March raid was then shipped to Blessed Hope by his mother; in a police report, according to a detective familiar with the document who asked to remain anonymous because it's a juvenile case , and in conversations with Kennedy, the teen charged that Wiggins had assaulted him, declaring beforehand, "I'm going to get the demon out of you and make you straight." In December 2016, DHR officials and county police raided the place in response to escapees' complaints of solitary confinement and hours-long exercise sessions, leading 22 students to be sent back home. Thus far, however, Kennedy's pleas for prosecution have been ignored. "Once again, Alabama law enforcement has failed to protect children." he says. (Wiggins said of the charges: "It's lies, all lies," before hanging up.)

Kennedy is equally outraged that former state Attorney General Luther Strange has been appointed a U.S. senator to replace Jeff Sessions, the new U.S. attorney general. "He [Strange] threw the children under the bus so he could grease the way for his political ambitions," Kennedy says. "All these politicians have lined their pockets with the blood of children."

Since the convictions, law enforcement and other public officials such as Morgan and Strange have begun trying to discredit Kennedy, using his final interview with the boys against him. While Kennedy says Knott forced the boys to take off their clothes—and the evidence from Vargas and others supports him—Knott told state and local investigators otherwise. Some officials such as Morgan and Strange now claim that's in part why they failed to act—even though they've long been aware such charges are bogus, Kennedy says. "We had questions about the way Kennedy conducted his investigation," Morgan told me, citing the naked interviews—something the former officer says is not true.

Meanwhile, the horrific legacy of Knott's program lives on, and many of the young people who went through the program remain severely damaged. Among them: Erin Rodriguez, now 18, once a pill-popping runaway in suburban Atlanta before her father sent her to RYA and later to the Saving Youth Federation until she was freed in the 2015 raid. "They would whip me," she says. "They stripped me to my underwear and bra and took out a belt and hit me until I bled." Back home trying to rebuild her life, she still has nightmares about her experiences at the facilities.

Robert, the teen who was told to put a gun to his head, is still struggling, too. After being released into the custody of his grandparents in a small Texas town, he continued to unravel. He's been arrested twice on drug charges. The latest incident occurred in the fall of 2016, when police found the traumatized, suicidal youth sitting by his mother's grave with a gun and some illegal drugs. They arrested him, and despite pleas from Kennedy that he needed mental health treatment, they sent him to jail where he remains today, unable to afford bail.

The traumas these young people face is why Kennedy continues to fight against abuse.

"One of my greatest satisfactions is knowing that these children who suffered so much at their hands know that justice has been served in some way," he says, but "you can't return the youth that was stolen from them, you can't restore the mental and physical damage that was done."

Adapted from Mental Health, Inc.: How Corruption, Lax Oversight, and Failed Reforms Endanger Our Most Vulnerable Citizens, by Art Levine. Copyright © by Art Levine, 2017. Scheduled for publication in May 2017 by The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc., www.overlookpress.com. All rights reserved.

Read more: A retired police captain reveals how his five-year investigation and letters from abused teens helped lead to the conviction of three counselors in a "Christian" boot camp. The interview with Captain Charles Kennedy was conducted by Angela Smith of HEAL and can be heard in its entirety here: www.heal-online.org/rya.htm.

Correction: A previous version of this story mistakenly identified the Mobile Police Department officer Kennedy spoke to about the Saving Youth Foundation as Police Chief James Barber. It was actually his brother, Captain John Barber.