Male and female brains are hardwired to be different. Men are programmed to be aggressive, assertive and strong, while women are emotional, nurturing and compassionate—right?

Well, maybe not, according to the most recent scientific evidence. You wouldn't know, however, from Hollywood's latest pop-science flick.

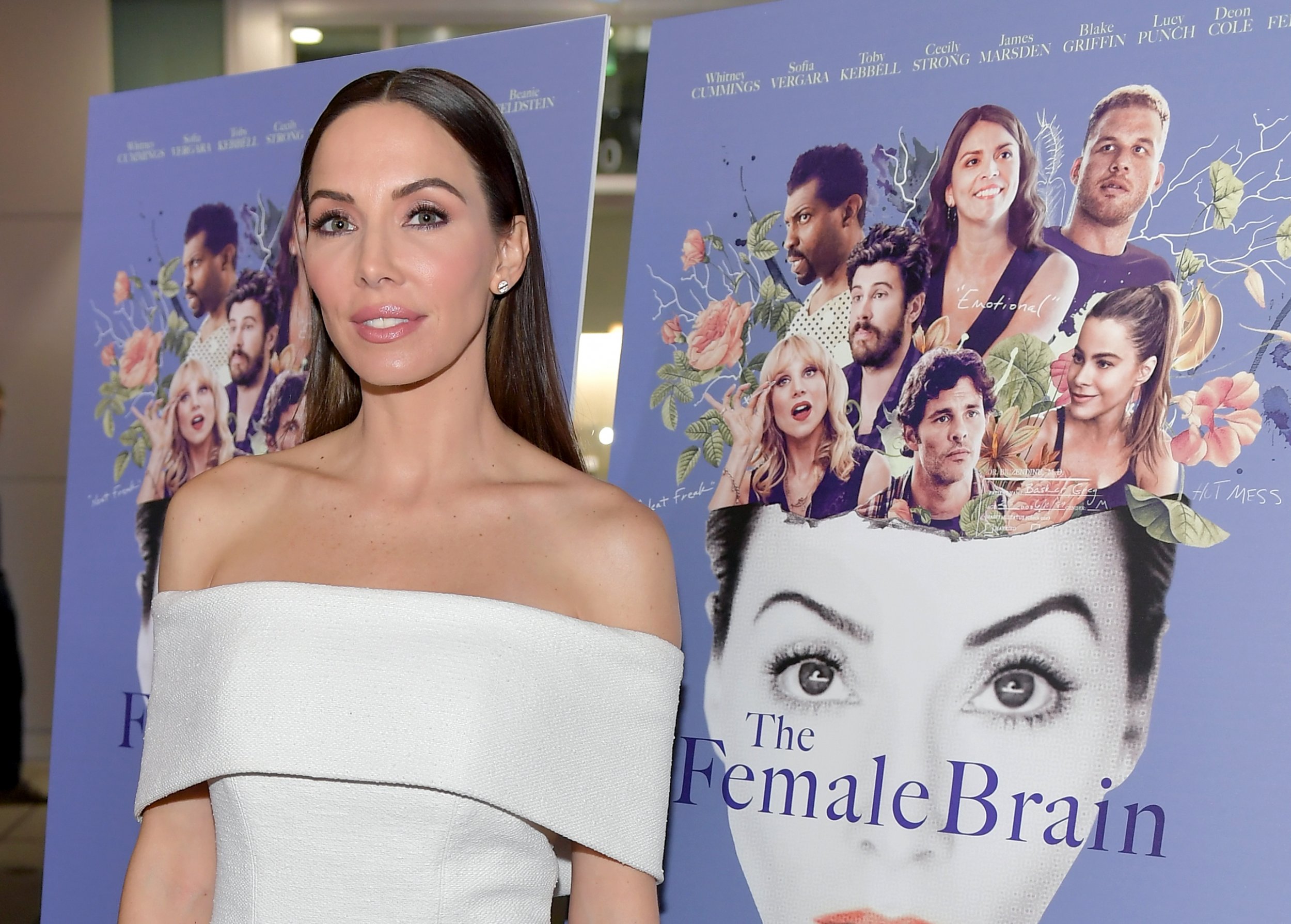

Friday saw the U.S. release of The Female Brain—a movie based on Louann Brizendine's best-selling but widely criticized 2006 book of the same name. Documenting the "science" behind heterosexual relationship woes, both the movie and book tread some pretty familiar gender-stereotyping ground. Think Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus—but with brain scans.

The Female Brain movie follows the fictionalized "Julia" Brizendine: a neuroscientist who explains the relationship dynamics of her friends through her research. But how accurate is the science in the film?

Newsweek spoke to five experts from the fields of neuroscience, psychology and even social neuroendocrinology to get to the bottom of the question: are female and male brains really that different?

Do women notice errors more than men?

According to the movie version of Brizendine, women are "hypervigilant." This mean they have a heightened ability to spot errors. The reason, she says, is that the area of the brain responsible for this activity is larger in women.

Read more: Study finds no real difference between male and female brains

The area of the brain is not named in the movie, but it is likely the anterior cingulate, neuroscientist Gina Rippon from Aston University in Birmingham, U.K., told Newsweek. There is no evidence, she said, that this part of the brain is "larger" in women. In fact, there is no contemporary scientific evidence that a bigger area in any part of the brain might elicit a "heightened" behavioral response, she added.

Can brain scans really explain our behaviors?

The whole idea of looking inside someone's brain to understand their behavior is flawed, according to Rippon.

She said: "You can't currently take a brain imaging read-out and, in the absence of any other information, reliably say what kind of behavior produced that response."

In other words, when you see an area of the brain light up on a scan, science isn't anywhere close to linking that to something that person has seen or done.

Do hormones make women obsessive?

Hormones are presented—in the film and throughout pop culture—as key drivers of human behavior. According to the movie depiction of Brizendine, women can limit the secretion of "flight or fight" cortisol by "getting obsessed with details."

Sari van Anders, a social neuroendocrinologist from the University of Michigan, told Newsweek: "There is literally no evidence for this effect, much less its explanation. Any scientist who made a claim like this without attending to the huge volume of science and scholarship about gender and work is not doing science."

Using hormones as an explanation for sex-based behavior differences relies on a link that is vastly overstated.

Van Anders said: "Indeed, one of the most important recent understandings within hormones and behavior is that scientists can find much stronger evidence of social behaviors changing hormones in humans, than hormones changing behavior."

It's not that hormones have nothing to do with sex and gender, van Anders said, but rather that our social and cultural experiences of gender can actually affect our hormonal make-up.

Can a woman unlock a man's genetic code by sniffing his pheromones?

A woman can instantly determine her genetic compatibility with a man by a quick whiff of his pheromones, Brizendine says in the movie. This, it turns out, is one of the less controversial claims of the film.

However, it still inflates what is really a minor link—and one that many scientists still question.

While the term "pheromone" is simply not used by scientists to talk about humans, our bodies do emit odors called "social chemosignals," Tel Aviv University neuroscientist Daphna Joel said. The link between these signals and genetic factors is real in both men and women, but very small.

Joel said: "Can we learn something about genetic fit from body odor? Yes. Can we learn 'everything we need to know' from body odor? No. Not even close."

Are male and female brains hardwired for difference?

The most fundamental scientific claim in the film, perhaps, is the idea that the "female" and "male" brain are hardwired to be different.

But this underlying premise, the scientists said, is flawed.

Rippon explained: "It doesn't actually make much sense to talk about any 'kind' of brain being 'hardwired.' You can change someone's brain in hours by teaching them to juggle or play Tetris or learn to be a taxi driver."

The idea that "female" or "male" differences are inbuilt assumes that sex and gender differences are predetermined, Joel added.

"In fact they may reflect differences between the ways girls and boys, women and men, are treated from the moment of birth," she said.

Van Anders said: "Neuroscientists have long ago jettisoned the idea that brains are static, and we know that what we see in adult brain scans reflects a lifetime of socialization."

Most research showing differences between male and female brains actually comes from animal literature, Gillian Einstein, a neuroscientist from the University of Toronto, said.

According to Einstein: "Mapping the animal literature onto human literature is not good science."

Rodents' bodies, for example, are too different to humans' to make reliable predictions about the brains of men and women.

Even in animal studies, few anatomical differences between females and males have been linked to significantly different behaviors.

Can movies like The Female Brain be harmful?

Fictional pop science like The Female Brain presents outlandish ideas as fact. "Some of the claims are so ludicrous I was laughing too hard to answer them," said Rippon.

But, the scientists agreed, promoting these unfounded claims can cause real damage.

Rippon said: "It reinforces inaccurate stereotypes. And it has been shown to reinforce widely held and inaccurate beliefs of the 'biology is destiny' type."

Cordelia Fine, a psychologist at the University of Melbourne, Australia, argued these stereotypes creep into the workplace and wider society. She said: "Encouraging people to think in this kind of 'gender essentialist' way is associated with more lenient evaluation of sexual violence (in men), and makes people less supportive of progressive gender policies and more comfortable with the status quo."

These misconceptions, van Anders agreed, make their way into policy: into approaches to transgender identity, sexual harassment, gender discrimination and gendered health issues.

Popular pseudoscience can even hold back scientific research. Van Anders said: "By misrepresenting, overstating, and making a hash of what we know, [it] limits what kinds of questions scientists think to ask."

While The Female Brain claims to promote the cause of women—that women and men are different, but neither is better—the comparisons made in the movie frequently position women as a problem to be solved because they differ from men, van Anders added.

"What some see as a minor linguistic issue is actually quite telling in painting men as the reference or norm," she said.

Read more: Why are women Uber drivers paid less than men?

Even if all the differences between women and men cited in the movie were true, Joel said, there are too many unknowns to build a distinctly different "male" and "female" brain.

"We would not know the source of [each] difference—nature or nurture. We would not know how it interacts with other characteristics of the brain to affect psychology and behavior...It would not add up with additional differences to create a 'male' or 'female' type of person or brain."

What sex differences are really important?

More important sex differences to investigate include those related to disease, Einstein said.

"Why will 70 percent of the people with Alzheimer's disease be women? Why do men present with heart attacks, on average, differently than women? Does a drug act differently in men than in women?" she said.

Life circumstances, working habits and the social expectations of men and women are just as important to understanding health disparities as physiology and anatomy. As with many other sex differences, focusing on the average "man" and "woman" misses the point.

"It's critical to bear in mind, even in disease and treatment, that some men will present as women do and vice versa," Einstein said.

The female brain, the experts agree, is something of a white whale. Brain scans and hormones aren't a simple way to understand and explain human behavior. But they can be hijacked as an easy romcom plot device to exploit society's fascination with the battle of the sexes.

"Criticising these kinds of claims has nothing to do with political correctness," Fine said. "Rather, it is about scientific correctness."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Katherine Hignett is a reporter based in London. She currently covers current affairs, health and science. Prior to joining Newsweek ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.