The best way to hear volcanic thunder is indoors and far away from an eruption. And thanks to new research from a remote island in Alaska, you can do just that. Here's what it sounds like, sped up at 10 times its natural rate:

As if volcanic eruptions weren't dramatic enough, they can also cause lightning and thunder. Scientists are still trying to figure out precisely why that happens, but even just isolating it from all the other clatter of an eruption is a valuable advance, as scientists report in a new paper accepted by the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

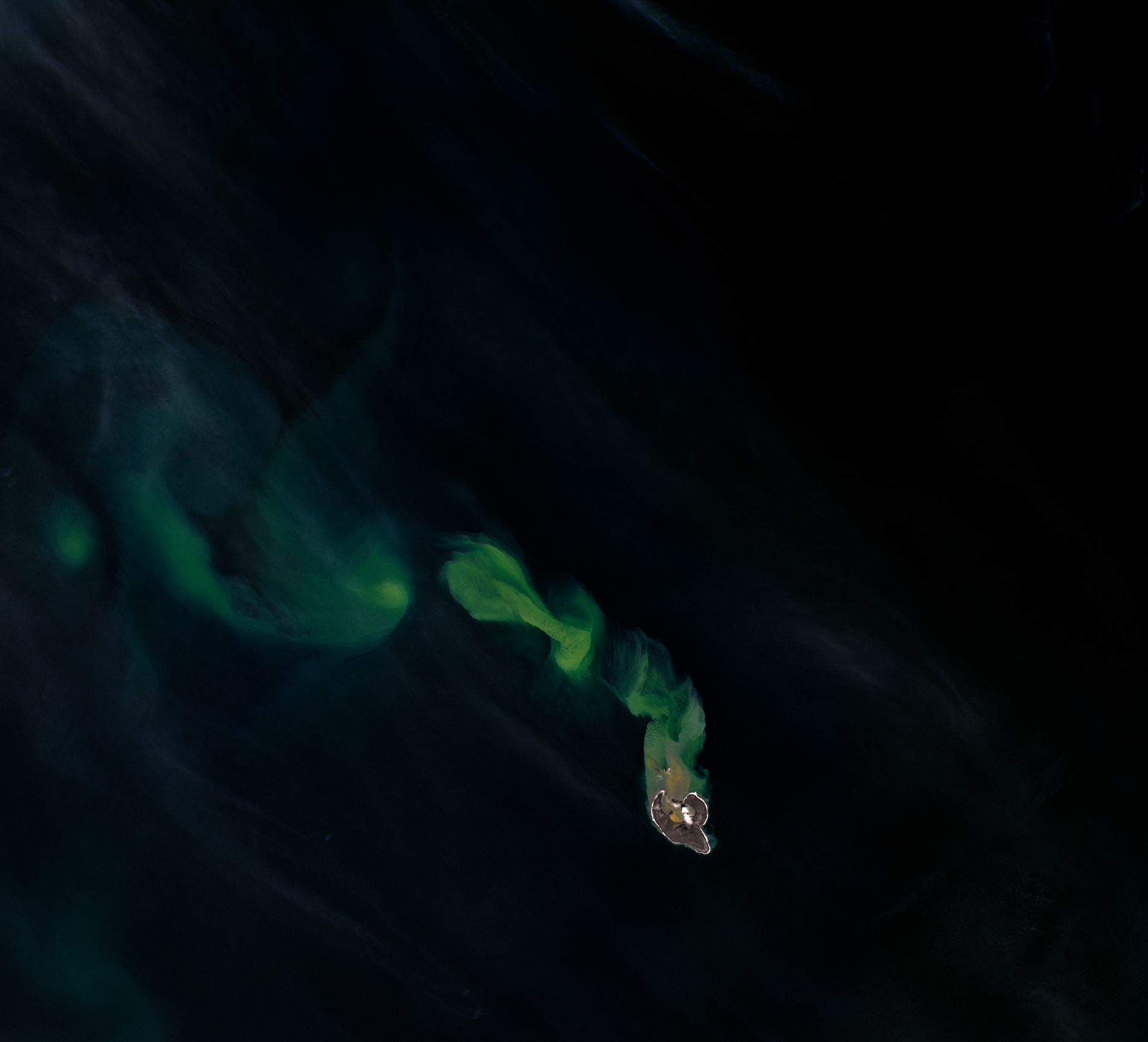

The recording was made possible thanks to a spree of activity last year at Bogoslof volcano in the Aleutian Islands, in the middle of the frigid Bering Sea. Over the course of nine months, the volcano erupted 64 separate times. Long before the eruptions began, scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey had set up microphones at a couple of nearby islands so they always know when an explosion occurs. After the eruption ended and they were able to dig into the data they had gathered, they realized they knew precisely when to look for the volcanic thunder that would logically accompany lightning.

Yes, that's right, volcanic eruptions produce lightning. "That's pretty rare to actually see," lead author Matt Haney, a geophysicist at the USGS Alaska Volcano Observatory, told Newsweek. Haney has been on the scene at two eruptions so far in his career, but hasn't spotted lightning himself. "That would be something to see someday, to actually see the lightning and hear the thunder." It's a well-documented phenomenon, although scientists aren't sure yet what causes it.

Scientists currently think the most likely option is that the lightning is a result of the chaos of the eruption itself. Colliding with each other on their way up out of the volcano could leave ash particles electrically charged, and if that charge builds up enough it could trigger the release of lightning. Another theory is that because the ash plume reaches so high into the atmosphere—3,000 or 4,000 feet up—it actually begins to act just like a thunder cloud.

Either way, the result is what looks like a perfectly normal lightning strike in the middle of a volcanic eruption. But because the lightning looks the same as ever, it's picked up by a network of detectors that look for faint bursts of light caused by lightning, which scientists have developed to better understand the weather. A strike close enough to Bogoslof and during an eruption—that's probably not a coincidence. "On our iPhones, we would immediately start getting detections of volcanic lightning," Haney said.

Read more: Decades-Long Kilauea Eruption May Solve Volcanic Lava Mystery

But at the time, Haney and his colleagues were too busy keeping an eye on the volcano itself to track down any thunder. "It was an exhausting eruption," he said. While there aren't many people living in harm's way, Bogoslof falls in the middle of popular air routes between the U.S. and Asia and, as Haney says: "Ash plumes and airplanes don't mix."

Once the volcano quieted down, Haney and his colleagues were able to dig into the data itself. In the new paper, they describe isolating two instances of volcanic thunder from the audio recordings taken near Bogoslof. (The volcano just barely sticks out of the ocean, so the microphones are located on nearby islands.)

Haney says there are more instances of volcanic thunder in those recordings and that the team will work to isolate them as well. He also pointed out that microphone networks are becoming a more common monitoring tool for volcanoes, so the technique could be used at other eruptions as well. Gather enough recordings, and it could help scientists crack the secrets of volcanic lightning.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Meghan Bartels is a science journalist based in New York City who covers the science happening on the surface of ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.