Simon Akam, the Englishman:

The Battle of Bannockburn Live begins at 4pm. We sit, surrounded by chainmail, watching the re-enactment of the 1314 clash, in which medieval Scotland fought for its independence from England, just weeks before contemporary Scotland may more peacefully slip away from its union with the rest of the United Kingdom.

I am at Bannockburn with my Scottish friend Finlay Young. We are both 28. We have read many of the same books, share many of the same life experiences, but there are distinct differences. As an Englishman, I am against independence. It seems a way to diminish Britain's already fallen status in the world. As a Scotsman, Fin is for it, seeing a chance for a better tomorrow. Our views clash, like the blunt swords on the field of ersatz battle.

If there is cliché in the reenactment it is there too in our relationship. Fin appears to be playing the role of son of the manse: fiery, passionate and morally superior. I find myself cast as the Englishness that Scotland wants freedom from: public school, Oxbridge.

Several weeks ago we both decided prejudice was not good enough. We chose to take a journey through the United Kingdom finding out what others on either side of the border think of a moment that seems to have snuck up on everyone and to examine what, at heart, it means to us. We began in London and headed to Cambridge, where I was born. We made our way to Oxford, that other divisive city of higher education. We traced a further English dogleg through Birmingham, Liverpool, Durham and Cumbria. Our first halt in Scotland was Dumfries; later we passed Edinburgh, Glasgow, Motherwell and Fin's family's home in Perth. Finally we tracked the east coast, via Dundee and Aberdeen to Fin's birthplace in Inverness.

At Bannockburn, halfway, we begin to take stock. Here are a clutch of Americans, festooned in mass-produced Scottish regalia that Fin later characterizes to his sister as "£19.99 kilts". All had the Scottish name Wallace; all sought roots.

"I've never been out of the States, this is my first time in Scotland, this is my first time anywhere," says Stephen Wallace, a 42-year-old carer from Floyd in Virginia. "I'm not as much into the history and culture and as educated as most of my clansmen, but I can tell you we marched in Stirling the other day, and I was marching with my fellow Wallaces, I really felt something in my blood, and the pride and the history."

Suddenly all is somewhat clearer. Passion and fire are scarce in the official Scottish independence debate. Both sides favour anodyne talk about relative economic advantage. Here at Bannockburn, listening to a foreigner unconstrained by local mores wax about a country to which he is only loosely connected, I see the heart as much as the head is central to the issue. What Scotland is lies at stake. That finding casts our trip into perspective. Maybe this is why Fin seems so unbelievably chippy.

Wimbledon, London

Our exploration of identity had begun a week before, on the first day of the tennis championships at Wimbledon in south-west London. The All England Club is a misnomer for the venue: Wimbledon smacks of a certain kind of England, an upper middle class state slaked by Pimms, fattened on strawberries, cream and artisanal baked goods. Fin made clear his suspicion of such a milieu, presenting himself like a freed-slave, incognito at an ancient Roman banquet. He suggested that, for many Scots, a "problem with posh" contributes to a desire for independence.

At Wimbledon in 2014, the reigning champion (if not the eventual winner) was himself Scottish. We watched Glasgow-born Andy Murray eviscerate a Belgian player in the first round. Beside us sat two English women, Clare Blathwayt and Hatty Fergie, childhood friends from the southern English town of Bath. They were middle class, posh even, yet both made it emphatically clear that they would prefer to take dour Murray home to meet their parents over Tim Henman, Great Britain's previous great white tennis hope and an unalloyed posh southerner.

On the surface, Wimbledon suggested positive Anglo-Scots interaction; a bastion of southern privilege embracing a wily Celt. Reality is more complicated. Murray is now an anointed British sporting hero, but it was not ever thus. Early in his career, asked on television whom he would support in a football World Cup, he quipped "anyone but England."

Arguably, Murray only scored his current acceptance through unprecedented competence. When asked about Murray's national identity, Fergie revealed these hidden layers: "Now he's British because he's won, when he used to always be Scottish."

Small Heath, Birmingham

Complexities of identity fell into sharper relief two days later in Birmingham. We aimed the sat nav for Small Heath, an area that had recently leapt to notoriety following alleged attempts to establish fundamentalist Islamic schools by stealth. At a children's playground, we spoke to Guljar Ahmed, a 29-year-old who recently immigrated to the UK from Bangladesh. As Ahmed's children made repeat descents of the slide, Fin explained his own sense of identity, with British ranking a definite second to Scottish.

Ahmed's response was vehement and insistent: "No, no, no." As at Wimbledon, sport provided the best way to parse these complicated feelings. "If they are playing football between the Bangladeshi and the England, I always support the England, because I am here . . . If the England is not in that game, and the Bangladeshis is in that football game, then I support the Bangladeshis," he said.

For Ahmed, coming to England was "my dream". On arrival, he was an enthusiastic assimilator. The Scots have never wanted that. Further north, at Edinburgh University, a sociologist called David McCrone would confirm that an oppositional element – not-being-English – is an important part of Scottish identity. By that stage, though, I had already drawn that conclusion from much closer quarters . . . Over 1,600 miles in a small black Vauxhall Corsa, the personal became the political. I had to admit that, in contrast to my international experience, I had never been to many northern cities. I had visited Kabul, but not Liverpool. I was embarrassed; physically embodying the north-south divide. Yet, I found inconsistencies within Fin's own narrative. We would in time encounter Scots whose failure to travel outside their own immediate ken seemed equally parochial. Much later in Perth too I would see that Fin's sister has more Le Creuset ironware in her kitchen than my own mother; our families are, in many ways, the same class. Yet, it seemed to me, Fin was attempting to wheel me across Great Britain as a breathing example of English privilege, a foil to his own typically Scottish working class hero demeanour.

On and on it went. "Simon is only friends with girls whose names end in A," he jibed on several occasions. He maintained his sense of self was explicitly rooted in "not-being-Simon", that he loved his home country, that he felt glorious and at home there, that the people were charming, but I wondered how much of the way the Scots as a whole behave is rooted in insecurity or envy. The broader Scottish identity, perpetually defined vis-à-vis the English, has shades of obsession.

Staveley, North Yorkshire

If that was the Scots then, what of the English? Well, mostly, they just seemed not to care.

One Friday evening we pulled into Staveley, a village in an affluent area of North Yorkshire. The Royal Oak pub sported exposed beams and wood panelling; it was thickening with weekend drinkers. I spoke with Anna Sykes, a 60-year-old farmer, and her 68-year-old second husband John. His career mirrored the collapse of British heavy industry; he began down a coal mine; now, in semi-retirement, he works part time in sales for a supermarket chain. The Sykes were concerned about jobs and housing for their children's generation; I asked if the potential fracturing of the United Kingdom lay on their minds too.

"It doesn't with me," said John. "I feel a bit sad really."

"We're nowhere near it, are we? It doesn't affect us," added Anne.

I raised geography, asking if hiving off a third of the landmass of the United Kingdom worried them. "Well not really, because it just seems it's mostly uninhabited," came Anne's reply. "They've got the small man problem," concluded John later. "They try and punch above their weight."

These views seem cartoonish but they are not without basis in fact. Scotland's population in mid-2013 was 5.3 million, compared to 53.9 million in England. Scotland accounts for around 8% of the UK's economy. Yet, when it comes to identity, what we heard in Staveley was also indicative of a fundamental failure to forge emotional bonds for continued union – something both Fin and I could understand, that could hold a nation, as well as our friendship, together.

The best diagnosis of the causes of this phenomenon came from Rory Stewart, a man whose CV reads like a latter-day boy's own adventure. Born into an upper class Scottish family, Stewart once walked across Afghanistan and served as deputy governor of two provinces in Iraq. We found him striding through the summer bacchanal in the Cumbrian town of Wigton, which he now represents as a conservative MP.

"We have not celebrated our country as being a country of different places with different identities in a way that federal countries find much easier to do," he said later, sitting among the biscuit crumbs in our Corsa en route to Penrith.

"History teaching in school is a problem; the lack of a written constitution is a problem . . . If one did it on an American model, where the constitution comes central to people's education, it would put into people's mind's that we have four nations, we celebrate the four nations, these are their identities, these are their histories . . . whereas in Britain you get the sense the English don't study any Scottish history in school, are barely aware of Scottish history or identity, and vice-versa."

Scottish Nationalists have laid out a path to independence should a yes-vote come on September 18. According to this timeframe, negotiations with the rest of the UK will conclude by March 2016, with Independence Day scheduled for the 24th of that month. Polls scheduled for 5 May 2016 would be the first elections to an independent Scottish parliament, which would in turn establish a constitutional convention to draw up a permanent written constitution.

Glasgow

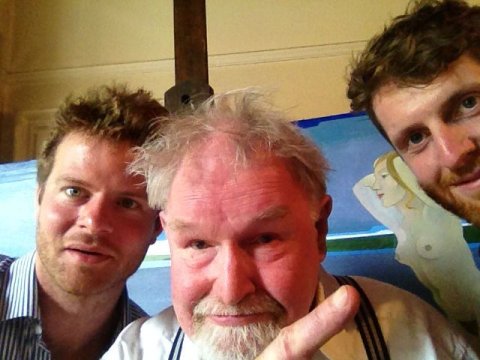

Fin and I crossed the border on the A74 motorway on a balmy summer evening. I had been to Scotland many times before but generally as a tourist, often to walk in the mountains. The urban country was less familiar. In Glasgow, a former industrial powerhouse now home to a vibrant creative scene, we assessed how Scottish artists perceive independence. We met Alasdair Gray, best known for his 1981 novel Lanark, in a studio-cum-library equipped with ink pots, unfinished canvases, and a filing cabinet labelled "Books to Come". Gray, who is 79, drew analogies between the future infancy of a standalone Scotland and his own creative development.

"You can only learn to govern yourself by doing it. Speaking from my own experience, painting a picture, or writing a book, you do it as well as you can, you stand back and look at it, you realise it isnae good enough, then you work to improve it. That's like anything you're trying to do for the first time. You're bound to get it wrong . . . everybody knows that Utopia is not suddenly about to dawn, but hope may."

This creative enthusiasm for independence was apparent later in the day too, with Stuart Murdoch, soft-spoken songwriter from Glasgow band Belle and Sebastian. "Without wanting to sound too bolshie, it is a political thing for me," he said. "I'm hoping, I'm naively hoping for an increase in the greater good. I'm just up for the greater good. I genuinely think in their heart people do want a fairer society, especially it seems north of the border just now, because they vote so differently to the rest of Britain."

In Glasgow we also met Eunice Olumide, a model-cum-broadcaster with 123,000 followers on Twitter. She was born in Edinburgh to Nigerian parents. "My friends from more middle to upper class backgrounds generally had quite positive views of Scotland – largely Edinburgh – and they only said really nice things, appreciative things about the city," she says. "However, I noticed when it came to my friends who were largely from more working class backgrounds, generally they've never traveled to Scotland before, and they had quite negative ideas about Scotland. Largely centered around two main ideas, which is – it's really cold here, and it's really racist."

Olumide maintained that, in her experience, Scotland was in fact substantially less racist than its southern neighbour, but the issue in general is highly topical. Economists agree that widespread immigration – of a sort that Scotland has experienced much less than England – would be necessary for a viable independent state. Throughout her education, Olumide was the only black face. None the less, the 26-year-old is sympathetic to the idea of her country going it alone.

"I genuinely believe that if Scotland was independent I would probably have more opportunity in this country, and I might not have to move to England, London, where I feel that I am at a disadvantage . . . This could be an opportunity to revitalise Scottish people, Scottish communities, because there is that Trainspotting culture that nobody talks about."

Perth

In Glasgow things between Fin and me had come to a head too. I announced that I would spend the evening separately, with an old Cambridge friend of mine. Over tacos and beer I explained my frustration at the tenor of the trip: I'm fed up with this I feel I'm being

exhibited over and again as an example of English privilege that does not mesh with who I am (he thinks I'm posh, he should meet some properly posh people) and this whole venture is a bloody morality crusade for Fin. I am never doing a collaborative project again. Etc etc. My listener was wise. "Don't you think you should maybe talk about it?" she said. The next morning we did, and things became better, for a while at least.

Fin's family live in the city of Perth. His parents' house has walls of white pebbledash and belongs to the local church. His father is a minister. They laid a lavish spread for me; cheese, meat and Shloer juice drink, favoured tipple in teetotal Scottish homes. I vaguely wondered again if they needed to prove something in the face of the condescension that I really did not think I held.

On this journey, I saw that the idea of The English manifests itself in Scotland more firmly than it ever does in England itself. I could understand the genuine excitement – in particular with artists and young people – at the prospect of building a better, or at least different future. It was a potent antidote to English apathy. But I came away from this trip sceptical of the Scottish tendency to self-mythologise.

Fin, so swift to pass judgement on my own life, responded tetchily to questioning of his own archetypal Scottish narrative. Back in London too, I heard in a radio debate one more Scot talk about how the referendum had revitalised political debate right across society.

I thought of a conversation we had in a rough pub in Maryhill, a poor area of Glasgow. "In this area 99% couldn't give a fucking shite," said a former union official. "99% of this area don't know how to spell vote."

Finlay Young, the Scotsman

"I don't have much affinity with the Scots," says the woman with the cut-glass English accent whose family has owned six thousand of our beautiful Aberdeenshire acres for more than 300 years. "Devolution has been a terrible failure. Everything changed as soon as the Scots were in power." Not for the first time on the trip, I bristle. It seems the problem with Scotland, for some at least, remains the Scots. By this penultimate stop in our fraught northward journey, I think Simon Akam may well agree.

Twelve days before, when all was fresh and friendly between us, we had set off from Simon's family home in Cambridge. We visited his old private school The Perse, where parents pay around £15,000 per year for a 25% chance their child will end up at Oxford or Cambridge. Well over half the country's median net household income, but relatively good odds.

The last time I visited a private school, I was one of 15 scruffy little state-school boys, demolished at "rugger" by 15 pristine chaps with English accents from one of rural Perthshire's private schools. Our preferred balls were spherical, not egg-shaped. We smarted in comprehensive defeat at the hands of our more privileged adversaries. To tribal little boys, the distant occupants of this rarefied layer of Scotland constituted the English. In rugby, as life, the first hit is important.

Westminster, London

Arriving in London we had first sought cold hard facts. The Scottish independence debate numbers game assumes this referendum business is all rational choice theory. Some surveys have suggested that being £500 per year better off after independence would see more than 50% of Scots vote "yes". At £500 worse off, only 15 % would vote "yes". Our kingdom for a grand.

Welsh economist David Phillips from the Institute for Fiscal Studies explained to us a dry world of fiscal gaps and revenues and taxes. "The disagreement, the crux of it in the short term on fiscal health, is oil revenue forecasts," Phillips told us. "The UK Office of Budget Responsibility forecasts are about £3bn for Scotland. The Scottish government is assuming £7bn." According to Phillips, the Scottish government figures are "quite sunny side-up".

However, Phillips told us that even if the oil dries up, Scotland could still be a wealthy economy. "Scotland is still about mid-table by western European levels." The nub of the issue is this: "However we looked at it, it looked like Scotland would face a more difficult fiscal challenge in future, even if there remains relatively high oil levels. There is high spending, and not enough tax to cover it." Difficult decisions on raising taxes or cutting spending would follow.

Later, at Westminster, we sat in the improbably steep press gallery above a frenzied House of Commons, watching Prime Minister's Questions. The words of Enlightenment Scot David Hume seem apt: "Reason is, and ought only to be, a slave of the passions". As the coming days would reveal, Scottish independence is about much more than the cold hard numbers game.

Strong arguments about democratic legitimacy underpin the movement. The Scottish Nationalists refer to a pronounced "democratic deficit". Maps of UK political party representation show the cool blue of the Conservatives dominating in the South, rising up to the warmer shades of nationalist yellow and Labour red dominating Scotland. There is only one Conservative MP at Westminster elected from a Scottish constituency. Yet often, as now, Scotland ends up with a Conservative-led government.

This argument also has an emotional edge. Those in favour of Scottish independence, in common with many left-leaning English counterparts, paint a picture of Westminster where parties are no longer ideologically divided, run by a cross-party elite of professional politicians – privately schooled, privileged, southern and posh. In the man standing at the dispatch box, Eton-educated Prime Minister David Cameron, this class based critique finds the embodiment of Scotland's bogeyman.

Labour's Shadow Scotland Secretary Margaret Curran MP, a working class Glaswegian, agreed. "We joke all the time that people from certain backgrounds do very well here, they are all privately-schooled and Oxford-educated." About 54% of Conservative MPs and 33% of the Commons overall, are privately schooled. The 7% of Brits whose parents could afford it also fill 71% of senior judge positions, and 54% of the top 100 positions in the media.

Curran was talking of Westminster when she called this a "burning issue" but it was one for Simon and me too. As we walked the corridors of Westminster power, we happened across a few of Simon's old Oxford pals. This seemed a somewhat joyful anecdote to add to the narrative. However, I felt asking Simon about problems of privilege and social mobility in the British establishment was a bit like asking a fish how the water is. The response: what water? He knew it was there, but couldn't really see it.

Dudley, Liverpool, Rochdale

In Dudley, a former Black Country manufacturing powerhouse, we heard about zero hour contracts and the rise of the UK Independence party (Ukip). Newly minted Member of the European Parliament, Bill Etheridge MEP, described an economic landscape where "factories have been largely developed into retail sites. All you see now is shops."

In Liverpool, Thatcher's malodorous ghost loomed large in the minds of those who spoke of a city still struggling to regenerate. In Falinge, a housing estate in Rochdale that suffers more than 70% unemployment, former soldier Kyle Horridge told us how the army had been an escape. "What else do young lads here have going for them?" Later, in Dundee, we would visit a food bank and see embarrassed faces take home bags of empty carbohydrates for their children. This year alone, almost 900,000 people across Britain have done the same. The picture was one of alienation.

Also later in the trip, admittedly as provocateur trawling for an outraged Scottish response, Simon would refer to the Scottish parliament as a "school council, and the First Minister a "glorified mayor". This banter reflected his wider worries about size. He often expressed concern about Scottish independence diminishing Britain's status. In Oxford, our breakfast companion, historian Hew Strachan, had agreed with him: "I think it would have a dramatic effect . . . perceptions are crucial, that's where it begins."

After travelling through these alienated parts of Britain, concerns for international status came to sound to me like vainglorious nostalgia for a Great Britain long since gone. What really diminishes us is our blithe acceptance of increasing inequality and entrenched poverty.

Glasgow

It would not be until we reached Glasgow, many bristles and jibes later, that these vexed poverty questions would cause it all to spill over for the Englishman and me. Banter suddenly became real and somehow this whole independence moment had everything to do with the gut-breaking sob of an idealistic and eloquent 16-year-old Glaswegian socialist, radical independence activist Saffron Dickson.

She clasped the Costa Berry Cooler cup tighter and looked at the Englishman in horror. "How can you even say that?" She sniffed and composed herself once more. "They're people." Simon looked at her with something like confusion. I'd learned in the course of our journey that any mention of socialism turns Simon into a dogged McCarthy-cum-Paxman. However, he'd only called into question whether the poverty she'd seen around her Glasgow home – "people without enough money to feed their bairns" – was really something we can hope to solve. The colossal sob that followed was catalytic, a youthful rejoinder to old, stale Britain, so resigned to its poverty and inequality.

Dickson was right. It's a great crying, sobbing shame on us. Britain is wealthy, but increasingly unequal. Earlier this year Oxfam reported that five wealthy families have more wealth than the bottom 20% of the UK population combined. London might be the richest, the jewel in the crown, but nine of northern Europe's 10 poorest areas can also be found on these islands of ours. Simon's question suggested the status quo as an immoveable object to be negotiated. For Dickson and many others, independence is the first sign in their lifetime of its malleability.

All this Scottish optimism, and my embrace of it, was enough to send our Englishman off to his next yoga class with at least five of his seven chakras out of whack. Scotland seemed like the insufferable child that has got it into her head that she is different, that she can be something else, something better.

That night we awkward bedfellows sought solace apart. "I just feel that Simon and I are looking at the same situation and seeing totally and utterly different things," I moped to my friend, a psychologist used to dealing with far more important concerns. She suggested that this might be because we are looking from very different places. Which is surely what this whole independence debate is about.

Inverness

As our northern endpoint Inverness drew closer, our journeys grew ever quieter. As the Scottish countryside flashed by the windows, I leafed through a book Edinburgh University sociologist David McCrone had given us when we had earlier met in Edinburgh, his 2009 co-authored edition, National Identity, Nationalism and Constitutional Change. "Above all, the relationship between Scotland and England was conceptualised in class terms, with England as the "posh" side," I read. "Scots define themselves vis-a-vis the English . . . as if looking in a mirror we see who we are in terms of our antithesis".

This is why prior to the trip, when one of Simon's female friends – with a name ending in a – had remarked "you are just the Scottish version of Simon", I had smiled, but imperceptibly stiffened. In some odd way, I realise my Scottish identity uncomfortably depends on this: I am, because I am not Simon. I realise now that the Scots probably have a more defined idea of English identity than the English do. In different ways, this is sad news for both nations.

This oppositional dynamic manifested itself throughout our trip. Scotland's Holyrood Parliament is the antithesis of the Gothic splendour of Westminster. In the independence debate, Scotland's First Minister Alex Salmond – couthy and down to earth – sets himself up very clearly as the antithesis of posh boys like David Cameron and leader of the No campaign, Alasdair Darling. In pursuit of independence, the Scottish National Party have sought to negate differences and minimise polarisation within the electorate. In that way they are a cipher; the SNP's broad one-size-hopefully-fits-all-scots image reflects how we see want to see ourselves.

The implication is that we can do it better than Westminster. Independence is portrayed as the only way to protect the things Scots value, the National Health Service, free education for all, a welfare state that protects the poor. This suggests Scots value these things more than the rest of the UK. When we talk of welcoming immigrants to support our economy, it sounds like an indictment of all those Ukip voting types down South. I don't think Simon found the sense of seething Scottish victimhood he was primed for. He found the only thing worse – a sense of Scottish superiority.

It all became too personal. He viewed my habitual long workdays as an absurd Scottish Protestant work ethic in Anglo-baiting overdrive. It's just how I work. I viewed his increasing need for daily yoga time and occasional refreshing naps as absurd affectations of middle-class privilege. That's just how he works. In my criticism of the status quo and excitement at the idea of change, he heard a chippy, morally superior Scotsman. In his acceptance of the status quo and his dismissal of any prospect of change, I heard a condescending, naysaying Englishman. By the end of our journey, we knew each other better, but thought each other worse. As it has for our nations, the independence debate pushed the latent complexities in our friendship to the surface.

Ultimately, it all mattered much more to me. It is Scotland alone that finds itself in a period of national imagining. The rest, like Simon, are excluded, observers of a party to which they are not invited. For me, Scottish independence is an opportunity for us to finally put our money where our myth is – no more, no less. We should take it.

Simon and Fin's ebook based on their trip, Englishman Scotsman: Two Friends. One Thorny Argument, is available now through Amazon. Watch them discussing their trip in the Newsweek offices below.