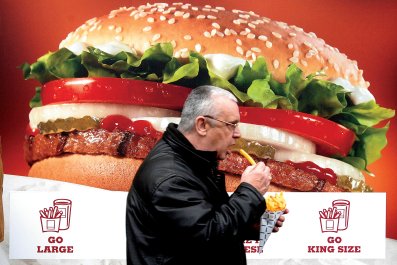

Technology and the Internet are so pervasive, so enmeshed in our everyday lives, that it's virtually impossible to disconnect. The latest additions to the Oxford English Dictionary include "binge-watch," "clickbait," "live-tweet" and "ICYMI" ("In case you missed it"). Schools are rushing to put laptops or tablets in the hands of every student. Recently, two 12-year-old girls attempted to murder their friend to please an Internet horror creature they believed was real. And thanks to Fisher-Price and CTA Digital, babies and toddlers can't even sit in bouncy chairs or learn how to use the potty without staring at a tablet.

Today, children and teenagers spend more than seven and a half hours a day using smartphones, computers, televisions and other electronic screens. And because they're so skilled at multitasking, all that texting, TV watching and Internet surfing adds up to nearly 11 hours of media consumption packed into those seven and a half hours.

And at what cost? How will all of this screen time affect their ability to socialize, talk to each other and relate in the world?

A new study found that tweens who spent five days at an outdoor camp, unplugged and media-free, were better able to understand emotions than their peers, who stayed home and continued their usual media diet. Researchers determined that face-to-face interaction, coupled with time away from technology, was the difference for the girls and boys at camp; while they showed significant improvements in recognizing facial emotions and nonverbal cues, the control group revealed almost no improvement.

"It's the most socially important study that I've ever been involved with, in the sense that it's so directly applicable to the real world," says Patricia M. Greenfield, a distinguished professor of psychology at UCLA and the study's senior author. "It has clear and immediate implications for education and parenting, and for solving a social problem that hasn't been recognized. And it is, to our knowledge, the first experimental study to look at the effects of new media on tweens."

The study, which will appear in Computers in Human Behavior this October, focused on 6th graders at a public school in Southern California. Fifty-one girls and boys spent five days at a nature camp with a "no screens" policy, where they hiked, studied the environment and learned to cook food outdoors, among other activities. Not once did they look at a smartphone, computer or television. They were compared to a control group of 54 classmates who remained at home, went to school, and spent as much time as they wanted plugged in.

Students were tested at the beginning of the five-day period, and then again at the end, to assess any changes in their ability to decipher emotions. In one test, photos of 48 faces—some happy, some sad, others angry or scared—flashed across a screen, two seconds at a time. The students had to record the emotion of each face. In another, they watched videos of actors in everyday situations. There was no sound, so the students had to assess what the actors were feeling simply by watching.

After five screen-free days at camp, the students showed significant improvements in recognizing both facial emotions as well as non-verbal emotional cues. "They were able to look at a happy face and, before they may have said it was angry, but after they identified it as a happy face," says lead author Yalda T. Uhls, a senior researcher with the Children's Digital Media Center @ Los Angeles and Southern California regional director of Common Sense Media. "It was surprising that in such a short time, the kids got better at recognizing emotion. That's the good news; it takes so little time to reconnect."

In the first test, in which the students were asked to identify the emotions of 48 faces, researchers found that girls and boys made fewer errors after five days at camp (a total of 9.41 errors, down from 14.02) than the control group did after five days of their regular routine (9.81 errors, down from 12.24). The kids at camp also improved their scores on the video test, going from 26% to 31% correct answers. Scores among tweens in the control group did not change, remaining at 28%.

The study's limitations are clear: It was difficult for Greenfield and Uhls to parse the individual effects of screen withdrawal versus face-to-face group experience versus time in nature. Yet they argue that the time tweens spent with each other—incited by reduced technology and media exposure—was the key determining factor in boosting their read on emotions.

The other big problem here is that it's difficult for children (or their parents) to disconnect. "You know how babies stare at faces? It's partly because they're figuring out who can they trust," says Uhls. "If there's a big iPad in front of the baby, yes, the baby will be entertained, but it's taking away from the baby's ability to look around the world. There's something really not right about that." Texting has become teenagers' prime method of communication, over talking on the phone, talking in person and using social media. Children and adolescents, however, need personal, face-to-face experiences to learn certain social skills. In the long run, those who can successfully decipher emotional cues have a better chance of developing strong friendships.

"This rapid improvement in reading emotions is positive and encouraging, but it could decline just as quickly if not maintained," says Greenfield.

Paying attention to how much time your children spend with devices; setting limits; spending time together as a family, device-free—these are all important steps parents can take.

"I'm pro-media and content, and I enjoy the best it offers, it's just that it's important to have a balance," says Uhls, a former Hollywood executive. "Give [children] time to go outside. If you can afford to send them away to a camp, do. Look at your own media use and what you're modeling."

As Greenfield puts it, "If people are aware of the costs, they will try to do something."