It's a glorious Monday morning in Rio de Janeiro, and I'm standing outside the city's Municipal Theatre with Manoel de Almeida e Silva, an author and former spokesman for the U.N. He is a neat man, with a head of soft gray curls, and he is carrying a backpack. He is explaining how a statue of Carlos Gomes, Brazil's most famous composer, came to be here.

In the 1940s, he tells me, Polish expats in Rio commissioned a statue of composer Frédéric Chopin to replace one destroyed by the Nazis in Warsaw a few years earlier. The Chopin statue was originally placed in Urca, a neighborhood near Sugarloaf Mountain, but in 1951, the city's mayor had it moved in front of the municipal theater, where the great Polish composer stood as if he were conducting the theater's orchestra. At Carnival time, citizens decorated the statue with flowers and musical instruments.

But in 1960, Paulo Fortes, a baritone in the Brazilian opera, worried that Gomes was slipping into obscurity, and so he raised money to commission a statue of the composer. Together with four strong men, he "confiscated" Chopin and erected the statue of Gomes in its place. In a kind of musical merry-go-round, the figure of Chopin, abandoned in a warehouse, was eventually returned to his original spot in Urca, where it now stands.

These are the kinds of details De Almeida e Silva learned while co-writing a new book, Secret Rio, released by Jonglez, a small French publisher that specializes in guides to the obscurer sides of cities. Each guide includes more than 200 entries, with a clear criteria for inclusion: If the place, sight, work of art, or example of architecture is commonly known, it is not included.

The book is a revelation, particularly for a city like Rio that is perennially dogged by stereotypes of beaches, bikinis and crime, and marketed more on its natural beauty than on its cultural heritage. Olympic cities tend to experience an uptick in tourism once the show is over: Having hosted 1.2 million visitors over the 2016 Summer Olympics, Rio wants to encourage more people to come. Secret Rio will likely do that by providing ideas that travelers will struggle to find in other books about the city.

Leaving behind the statue of Gomes, de Almeida e Silva and I continue our walk, weaving between office workers and street vendors in Centro, Rio's downtown. In an underground parking lot, he leads me to a gap occupied by two giant chunks of what was once seawall, rediscovered by workers when the parking lot was built, with a plaque explaining its origin. "I thought it would be good to bring you here," he says, "so you can see where the sea once came to." The city erected the wall at the beginning of the 20th century to keep back the water and protect Rua Santa Luzia. That seems unremarkable enough, until you learn that the road it protected had been built by King Dom João VI to access Santa Luzia—a church dedicated to the saint of eyesight, whom the king regularly prayed to in an attempt to help his blind nephew. And in 1922, the wall was buried by earth liberated from the flattening of a small hill known as Morro do Castelo—part of an extensive plan to extend and develop the city by filling in its swampy areas and reclaiming land from the sea.

The increase in Rio's land mass in the 1920s was crucial to its development; the manmade areas of low, flat land are obvious when seeing the city from up high. Which is where De Almeida e Silva and I are now, on a terrace tucked away on the 14th floor of the former Ministry of Finance, looking out towards Guanabara Bay. He points out the old municipal market, an unusual octagonal tower with a dome on top, and the many buildings built in 1922 for the Independence Centenary International Exposition, which celebrated Brazilian independence. More than 6,000 exhibitors took part in the fair, which was housed in 20 pavilions. Some of the buildings that remain are The Museum of Image and Sound, the Cultural Center of the Ministry of Health, and the Petit Trianon, a small copy of the original château in Versailles, with a garden designed by Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx, renowned for his use of curves and flow and tropical plants.

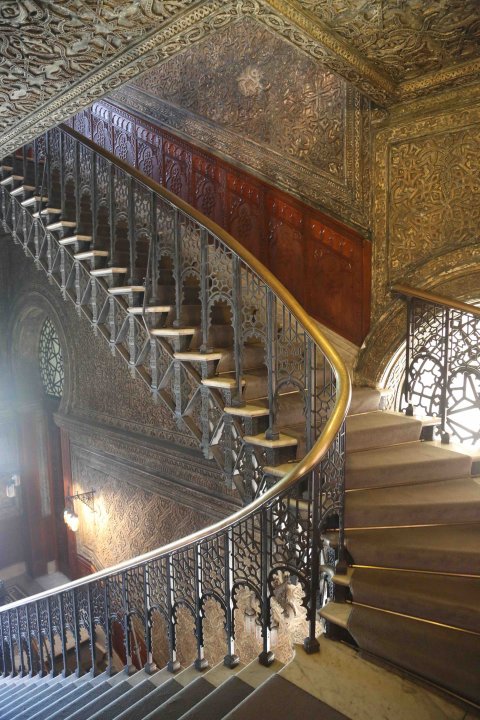

The former finance ministry, despite its bureaucratic purpose, contains several impressive works of 1940s Brazilian art. Inside, a spectacular, neoclassical kidney-shaped staircase of marble and black ironwork created at the same time as the building in 1943, snakes up between the vast floors. On the outside wall, three bright, well-preserved ceramic mosaics of indigenous figures in rural, Amazonian settings by 20th century Brazilian artist Paulo Werneck flank glazed ceramic statues by Leão Velloso, a sculptor from the same period. One is of a powerful, almost naked woman surrounded by intricately carved animals and plants, and the other depicts a man wrestling a leopard. Both made of glazed ceramic. De Almeida e Silva explains that artists working in the 1940s often used indigenous motifs as part of a movement to value all things Brazilian. I doubt more than a handful of visitors pass by these works of art in a week.

Close by is the former ministry of health, a notable example of modernist architecture designed in 1935 and 1936 by Lúcio Costa, a Brazilian architect and city planner who built the country's capital city, Brasília, in the late 1950s. His team, which included now famous Brazilian architect, Oscar Niemeyer, invited the father of modern architecture, Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, to oversee the project. True to the modernist style, it features a raised ground floor to allow for the free movement of people under the building, and brises-soleil, an adjustable sun shading system fixed over the windows that deflects sunlight and the breeze. Blue-and-white tiles made by Candido Portinari, a Brazilian neorealist, cover the walls at street level. They are awash with bobbing seahorses and repeating scallop shells, as well as other sea life scenes. Few know about the hidden garden on the roof, and the Burle Marx hanging garden on the second floor.

Secret Rio does not confine itself to the city's historical center. The book covers physical ground, history, time, and religions; it will steer you to the Russian Orthodox Church built in 1927 in Santa Teresa by immigrants escaping the Bolsheviks and it will help you discover the only bird cemetery in the world. Not all of the sights included in the guide are high art. Others to discover include: the Batman sign high in a ventilator shaft in a Copacabana metro station that was created by a worker after his child believed his father's joke that it was actually the Batcave; a hangar in Santa Cruz that housed Zeppelin airships until they fell out of favor after the Hindenburg disaster in 1937; and small neighborhood projects like the Museu da Maré museum, which tells the history of one of Rio's bigger and more dangerous favelas, or slums.

De Almeida e Silva and his co-authors say they had fun researching the book, exchanging little stories about the city they have known their whole lives. "It's a book for people living in Rio," he says. "People want to be a part of where they live, to learn and contribute. Rio is often talked about as a broken city. I hope this book goes some way to mending it."

Secret Rio is published by Jonglez publishing in English and Portuguese at 17.90 euros ($19.95)